The learning team around the child is at the heart of the Gesher Way. A trans-disciplinary approach is taken with every child which sees the teachers, therapists, teaching assistants, parents and carers working together beyond discipline-specific approaches. This ensures that each child has an individually tailored provision of care throughout their school day. The learning team commits to equally and continually discussing the needs of each child and providing the most effective education and therapeutic model of practice. They aim to understand each other’s roles and subsequently work together to combine skills and understanding.

Upon starting at Gesher, a range of formal and informal assessments are used to understand each child’s needs and provide individual and group therapy based on what is identified. Furthermore, the therapy team works alongside classroom teachers to provide the appropriate equipment, environment and provision for each learner.

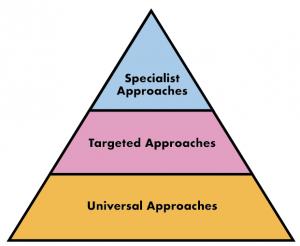

Gesher offers a range of core therapies, including Speech and Language Therapy, Occupational Therapy, Art Therapy and Dramatherapy, to support with their learning and developmental needs. These therapists work at Gesher on a full-time basis and utilise a three-tiered approach: universal (for all), targeted (for small groups), and specialist (for individuals).

All children benefit from the therapy team working within the classroom, offering ongoing advice and providing training and workshops for staff and parents. Each of the therapy team focusses on a specific area of support, and at Gesher this is presented in the following ways:

Speech and Language Therapy

Speech and Language Therapy

-

Providing advice, assessment, and intervention to help support and develop skills in the areas of: language, speech, social communication, voice, fluency, swallowing, and augmentative and alternative communication (AAC).

-

Using specialist skills to work with students, staff and families to develop functional, child-centred goals which may enable them to access their wider environment more confidently and capably.

-

Implementing evidence-based programmes, resources, and support into the school environment to ensure that students are able to meet their full communication potential.

Occupational Therapy

Occupational Therapy

-

Through assessments, the OT will develop creative and holistic goal-focused interventions that teach everyday life skills; these include fine and gross motor skills, as well as more specific tasks such as toileting, eating, self-care and dressing.

-

Support children to build a better relationship with themselves, through confidence building, emotional regulation strategies, and developing an understanding of their strengths and needs.

-

Facilitate opportunities for children to develop skills that form the foundations for future achievements.

Dramatherapy

Dramatherapy

-

Providing a safe space to promote wellbeing, where a creative environment may be more conducive to therapeutic progress than more traditional psychotherapy techniques.

-

Utilise role-play, embodiment, storytelling and projection to help explore personal and social situations; help to develop a broader role profile and develop adaptive functioning skills

-

Using play, art, movement and music as alternative means of communicating; apply psychological models and theories to promote positive mental health.

Art Therapy

Art Therapy

-

Art therapy is an effective way for children and young people to explore and create meaning from their experiences, in a safe and confidential space, free from judgement.

-

Different mediums and resources are used for the child to choose from and express their internal worlds. For children, play and the arts can be the common language, so the value of the arts in therapy and education can be immeasurable.

-

Using the creative arts can help with self-regulation and counter-balance stress hormones. In addition, sessions can help a child grow in self-confidence and empower them to make decisions, as well as, encouraging a growth mindset and helping to build resilience.

-

The aim of Art Therapy is to provide children and young people with a ‘voice’, when words are not as effective and to achieve a general sense of well-being, so children feel better equipped to learn and cope with big emotions and the stresses life can bring.

All of these strategies are brought together within the school environment, and the school team works with families and carers to ensure continuity and consistency within the home also. In addition to this, Gesher has an in-house educational psychologist who works at the school weekly. They work collaboratively with the rest of the therapy team to ensure the needs of the children are thoroughly met through a multi-disciplinary and holistic approach.

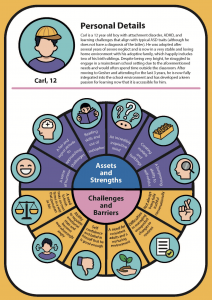

Gesher Personas

Click on the cards below to get a better understanding of the types of students we have at Gesher.

The following case study looks at the initial therapeutic experience of Shaun, who joined Gesher at the age of 9 years old having been permanently excluded from his two previous school environments. His joint diagnosis of autism and ADHD had impacted significantly on his ability to learn in a mainstream environment, with numerous incidents of challenging behaviours being noted by the professionals working with him. Shaun was unable to read or write, and demonstrated clear signs of post-traumatic stress when faced with any academic pressures or placed within a school environment.

Shaun began attending weekly Dramatherapy sessions from his second day at Gesher. He was struggling to engage with the school environment, and when we spoke, he alluded to feeling very distrustful of schools in general, and stated that he was fed up with being told what to do. I was aware of Shaun’s previous experience in a school where he had been improperly restrained by several adult members of staff, and he had disclosed to an educational psychologist that he had felt physically violated and endangered during these incidents. I believed that the Dramatherapy space could have a significant role to play in addressing that distrust, and being the foundation for the emotional healing that Shaun had yet to experience. However, I was very aware that it Shaun should have choice to share with me the information about his previous experience at school, and would likely only serve to further his institutional distrust if I was to broach it first.

One of the huge benefits of a Dramatherapy intervention is that it’s very nature allows for flexibility in responding “appropriately to each child’s needs, with the aim of maximising their potential” (Godfrey & Haythorne, 2013:21). For a child such as Shaun this was incredibly important in helping him to feel safe by not feeling metaphorically constrained by the process, and therefore helping to diminish the association he felt between education institutions and being constrained physically. With the disclosure of his previous school-based trauma yet to be forthcoming, I instead focussed on ensuring Shaun felt welcomed into the therapy space and allowed the initial couple of sessions to be almost completely child-led; as with many individuals with learning difficulties who had “suffered vilification for their incapacities…the straightforward acceptance of who they are, in the present moment, can of itself by reparative” (Haythorne & Seymour, 2017). The sessions were going well although I still sensed a high level of anxiety from Shaun and a reticence to expose himself and be emotionally vulnerable. I was curious as to what the catalyst would be to enable this to happen.

Then suddenly, towards the end of his first three weeks at Gesher, Shaun demonstrated some challenging behaviours in response to being asked to come in promptly from the playground. A colleague came to inform both myself and the class teacher that Shaun was extremely upset and asked if we could come and support with his emotional state. As we arrived in the playground area, we witnessed Shaun attempt to climb the fence so as to leave the school, and when his class teacher intervened to ensure his safety, he began to lash out physically and verbally, and screamed loudly in distress. After we both tried unsuccessfully to de-escalate Shaun’s emotional state, and ensure both his and our physical safety, his class teacher ultimately had to restrain him using the TeamTeach technique. She held him gently by the forearms for a minimal amount of time, tucking his arms and legs in whilst encouraging him to move away and take space in the playground to calm himself once she felt he was calmer. Shaun reluctantly agreed to do this and spent around 15 minutes walking around the perimeter of the playground, seemingly looking for a way out but not acting upon it any further. After a while he appeared significantly calmer, and so I approached him. He began to share quite quickly what had happened; he had been upset by being asked to come inside several times as it had reminded him of his old school, where there were lots of rules and where he had been physically “choked” by the headteacher reasons unknown to him, prior to them “kicking him out” of the school. This experience was obviously dwelling on Shaun, and despite the bravado he was demonstrating, he was clearly anxious that he was going to be asked to leave yet another school. I thanked Shaun for sharing this with me, and asked if he wanted to have a Dramatherapy session to talk through what had happened, which he readily accepted.

As we sat and reflected on the incident, Shaun appeared at a loss for words. I observed aloud how his teacher had restrained him briefly and asked how he felt about it in comparison to what had happened at his old school. He acknowledged how different the two experiences had been, and through the use of emotion cards and drawings, I was able to facilitate a more conscious understanding of Shaun’s emotional state and what the triggers were for his distress. It was apparent from this work that Shaun was experiencing significant conflicting emotions around what had happened at his previous school: shame, confusion, anger, sadness, rejection. These feelings clearly had the potential to overwhelm him, and as such I was welcoming of them so that they could be “regulate[d] within the therapeutic process to ensure mutuality and authentic connection in which to explore…without judgement and humiliation” (Sanderson, 2015). Moving forward, we began to utilise various Dramatherapy techniques such as role-play, embodiment, and Neuro-Dramatic-Play (Jennings, 2011) as a way of helping Shaun to rediscover trust in others and belief in himself. The ingrained negative experiences that he had experienced previously began to be transformed with the support of the therapeutic intervention. Specifically, the automatic neurological reactions that had been previously been demonstrated began to change as the new positive experiences Shaun partook in within the therapy environment “strategically stimulate[d] the brain’s firing…to voluntarily change a firing pattern that was laid down involuntarily” (Siegel, 2011).

Being a full-time presence in the school was an incredible assistance in enabling me to support Shaun during these moments. I was able to witness the incident and therefore talk openly with him about it, and demonstrate that I didn’t hold him to blame or judge for it – in doing so, it allowed Shaun to open up at last about his previous traumas around being restrained, and I could confidently and compassionately discuss what I had seen as a neutral witness to the safe restraint that was used on him. My first hand perspective of the situation was able to support greatly with Shaun’s healing, and we continued to build upon this in our sessions to come. This wasn’t to say that Shaun always found it easy to share how he felt moving forward, but our shared experience of his traumatic response enabled us to develop a clearer and easier level of understanding; when the words wouldn’t come, Shaun would use mime and art, or we would jointly create something out of Lego or Play-Doh or cardboard as a way of processing his feelings on a more symbolic and metaphorical level. The fundamental premise of the use of metaphor as a process in Dramatherapy is that “it is a way of encapsulating human experience that is accessible to everyone” (Haythorne & Seymour, 2017); for children such as Shaun whose needs may make it difficult to communicate their feelings at times, metaphor therefore proves to be an invaluable asset in giving them a voice that is often ignored within our society. Thankfully, the broad range of resources available at Gesher only served to make these non-verbal communications more nuanced and easier to interpret.

Being able to respond to Shaun almost immediately after his challenging moment also meant that he was able to accurately reflect on how he was feeling rather than allowing it to build into a shameful memory akin to his previous experience of being restrained. Although there is much to be said about the importance of ensuring therapy is kept to a designated timeslot each week, within the school environment it has instead felt beneficial to respond to the children relatively soon after experiencing challenging emotions as they can work through feelings that they would otherwise find difficult to recall and reflect upon due to their emotional processing difficulties.

However, it must also be noted that when working alongside a child with ADHD, there is still a need for “clear, boundaried work that helps to contain their behaviour and structure their thought processes” (Dix, 2012). Appropriate use of Dramatherapy can also help to “create natural chemical changes in the brain and allow the child to develop new strategies for developing calmness managing behaviour” (Dix, 201). To address this and ensure that the use of adhoc support provided outside of regular planned therapy sessions remained safe and productive, I ensured that like with all the other children I work with, Shaun and I had a ritual that we would use at the start and end of each session to serve as the clear transition between his Dramatherapy process and his social/academic interactions around the school. We ultimately devised a special handshake that has acted as “a container for change, for the journey, for the adventure” (Jennings, 1990:62) in Shaun’s therapy throughout his time at Gesher.

After several months of working with Shaun, the use of Dramatherapy continues to evolve. Having demonstrated huge emotional growth and being able to reflect upon his previous traumas with an insightful level of maturity, Shaun has presently moved on to accessing the sessions as a way of processing his interpersonal relationships and the interactions he has within these. I continue to be privileged to support him with his wellbeing in such a well-supported environment, and have found it extremely rewarding to see how Shaun has used his sessions as a means of facilitating such a significant level of personal growth and healing.

References

- Dix, A. (2012) Whizzing and whirring: Dramatherapy and ADHD. In: Leigh, L., Gersch, I., Dix, A. & Haythorne, D. (eds.) Dramatherapy with Children, Young People and Schools: Enabling Creativity, Sociability, Communication and Learning. London: Routledge. pp. 51-58

- Godfrey, E. & Haythorne, D. (2013) Benefits of Dramatherapy for Autism Spectrum Disorder: a qualitative analysis of feedback from parents and teachers of clients attending Roundabout Dramatherapy sessions in schools. Dramatherapy. 35(1) pp. 20-28. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com (Accessed 12/06/2019)

- Haythorne, D. & Seymour, A. (eds.) (2017) Dramatherapy and Autism. UK: Routledge

- Jennings, S. (1990) Dramatherapy with Families, Groups and Individuals: Waiting in the Wings. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Jennings, S. & Gerhardt, C. (2011) Healthy Attachments and Neuro-Dramatic-Play. London: Jessica Kingsley

- Sanderson, C. (2015) Counselling Skills for Working with Shame. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Siegel, D. (2011) Mindsight. UK: Oneworld

David is a young boy with autism spectrum condition and ADHD, who joined Gesher at the age of 7 following difficulties in his previous school environment; he was shy, highly anxious, withdrawn, lacked self-esteem, and was experiencing increasingly physical melt-downs. He was regularly excluded from school and was the victim of peer bullying due to his increasingly apparent differences. His parents were also undergoing a separation, further adding to his confusion and diminishing his trust in adults. This is particularly difficult for any child, let alone a child with ASC wherein they often experience what can be described as ‘mindblindness’ (Baron-Cohen, 2008), a difficulty in understanding Theory of Mind which makes it challenging to comprehend their own emotional struggles as well as their interpretations of others’ feelings and behaviours.

Following the Gesher assessment process, it seemed highly likely that David’s behavioural issues were due to his frustration around being unable to access the world around him and the overly-stimulating environments he was encountering on a day-to-day basis. Whilst the specialist learning resources and staff support that Gesher provides would be able to address the immediate challenges that David was facing, he would require more specialist intervention so as to address the psychological trauma he had experienced, and subsequently help him develop his emotional literacy moving forward.

Upon meeting David and reading his case history, the compatibility of the techniques and processes used within dramatherapy seemed highly relevant in addressing his emotional needs. Helping him to feel safe and rebuilding his trust in adults would be a vital part of it, and this would be achieved through the use of having the sessions be in a regular time slot, a “predictable space and…strong containing rituals, which allowed [David] to feel safe enough to begin to explore and make connections” (Davidson, 2017). As the weeks progressed, David became increasingly relaxed and playful within the therapy space – through the use of creative expressive activities and play, dramatherapy was providing David with the opportunities to practice “rewarding new social experiences, whilst making the rules underlying social behaviour explicit” (Dooman, 2017). It was also a chance for David to find pride and strength in himself as an individual – drama and theatre are innately about providing a stage for performers, and dramatherapy is a metaphorical representation of this. In the sessions, David learnt that his “voice [was] respected and valued, and the therapist is the kindly audience or ‘witness’ to what they want to show” (Haythorne & Seymour, 2017). This in turn was something that David was able to apply in other areas of his life, as he begun to transfer the confidence he had found into building new friendships with his peers and engaging more profoundly with the learning environment.

The sessions with David were almost completely led by him – as with many children with SEN, David had often experienced a lack of personal control and autonomy within his life thus far – regularly being told what to do, how to dress, what to say, where to be, how to behave, etc. Whilst it can be of huge benefit in helping to make a child feel safe, there is a fine line between doing so and becoming overbearing and frustrating for the individual in not allowing them any freedom of expression. By allowing David to lead and providing him opportunities to control the environment around him, he was able to facilitate his own personal growth and demonstrate social-emotional development in other areas of his life.

References

- Baron-Cohen, S. (1997) London: The MIT Press

- Davidson, R. (2017) Entering Colourland: Working with metaphor with high-functioning autistic children. In: Haythorne, D. & Seymour, A. (eds.) (2017) Dramatherapy and Autism. UK: Routledge. pp. 16-28

- Dooman, R. (2017) Assessing the impact of dramatherapy on the early social behaviour of young children on the autistic spectrum. In: Haythorne, D. & Seymour, A. (eds.) (2017) Dramatherapy and Autism. UK: Routledge. pp. 137-155

- Haythorne, D. & Seymour, A. (eds.) (2017) Dramatherapy and Autism. UK: Routledge

Alfie joined Gesher at the age of 4 in 2017. He has a diagnosis of autism and he presented with very high sensory needs, under developed self-care skills, difficulties with motor development and with social interaction.

Alfie would struggle interacting with peers and adults. He would stand too close to others during a conversation and he would not maintain eye contact. It was reported by his family that Alfie also did not participate appropriately during family outings and activities with his friends.

Alfie’s sensory needs were particularly challenging in the area of proprioception. He struggled to effectively grade the amount of force that was required for movement, for example he held a pencil very tightly and pressed on the paper with excessive pressure. He also would chew on toys clothing and objects and frequently break things from pressing too hard on them.

Alfie also struggled with tactile, visual and auditory processing. He would become easily distracted by these stimuli, often to the point where he would become overwhelmed and unable to focus during classroom activities.

The area of praxis was also difficult for Alfie. Movements and activities that most people do automatically would be very difficult for him. For example, Alfie would fail to complete tasks with multiple steps such as building to copy a model for Lego or blocks to match a model. He tended to play the same activities over and over and struggled to come up with new ideas for play. When in a situation requiring imagination, Alfie would become anxious.

Since being at Gesher, Alfie has benefitted from a sensory sensitive environment within the school to support his sensory needs. In the classroom these experiences include personalised equipment and seating and sensory experiences within lessons. He also has access to daily OT designed sensory circuit aimed to support his transition into school and prepare him for the day’s learning. Alfie also participates in daily soft play as a sensory top up during the day. “15 minutes of sensory input is evidenced to provide up to 6-8 hours of regulation”. Along with this, Alfie has access to daily sessions in the sensory room, regular movement breaks and sensory breaks as needed throughout the day. Part of the OT’s role is to ensure that the school incorporates modifications to cater for sensory difficulties. For example, students can use active seating or pressure garments when required, they wear indoor shoes that help minimise foot noise, there are minimal visual distractions in the classrooms and students can use ear defenders, chew toys, sensory toys etc. as required. Students also become educated in the use of the ‘Zones of Regulation’ approach, so that they learn to identify and label their emotions and thereby put in strategies to help prevent them from becoming overwhelmed.

All of these sensory motor supports have had an immense impact on Alife’s ability to regulate his central nervous system so that he now maintains a calm alert state and he rarely has episodes of dysregulation.

Alfie’s self care skills have been slowly improving since being at Gesher school. He is now able to dress himself independently – a skill that he did not have when he first started at Gesher. All of the students are encouraged and supported to be as independent as possible at Gesher. Alfie is given support to transition and engage in new activities; from observing a new activity through modelling, before experiencing it himself and once he has learnt something he is able to repeat it to ensure his mental and muscle memory become established.

Gesher school has OT at the very heart of it. The OT works from a 3 tiered model working from a whole school, targetted and individual approach to ensure that each student has the best chance to achieve their potential and maintain a ready state for learning.

References

Understanding your child’s sensory Signals, 3rd Edition (2015), Angie Voss, 2015. P.129

The Out of Sync Child (1998) C. Stock Kranowitz. Skylight Press, New York

Gregory started at Gesher School in November 2018 at the age of 6, after it was determined that his previous school setting was not able to meet his level of need in terms of learning and communication.

Gregory has agenesis of the corpus callosum, a rare birth defect in which the two hemispheres of the brain do not connect. This has resulted in learning difficulties that impact on his ability to access a mainstream school environment. As well as his learning difficulties, Gregory has diagnoses of verbal dyspraxia and oral dyspraxia. His verbal and oral dyspraxia make it extremely difficult for Gregory to co-ordinate the movements required for speech and makes it hard for those around him to understand what he is trying to say. Gregory also has a language disorder which impacts on both his ability to understand and use language. Due to Gregory’s complex communication needs, he requires a range of varied speech and language interventions delivered at specialist (individual), targeted (small group) and universal (whole school) levels.

When first starting at Gesher, Gregory presented as shy and timid and was described as reticent to socialise with both peers and adults. He became frustrated easily when communicating with those around him and being unable to get his message across, would lash out at staff members by pulling their hair or refusing to engage entirely. Gregory was also described as anxious in environments where he was required to communicate and was highly reliant on adults to communicate on his behalf and interpret all his needs and wants.

In the short time that Gregory has been at Gesher School and has had access to regular speech and language support, both within the classroom environment and individual sessions, his confidence, independence, and enthusiasm to communicate has increased exponentially. As speech and language therapy is embedded into every aspect of the Gesher school day, Gregory has been provided with a large number of communication opportunities in a range of contexts and his motivation to engage socially, despite finding it difficult to communicate verbally, has been fostered at every turn.

When exposed to a supportive and language rich classroom environment, Gregory has thrived in his ability to interact and connect with those around him and is continually developing all aspects of his communication through both direct and indirect speech and language input. Looking towards the future, Gregory will begin to be supported to communicate further using augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)* technology to supplement his developing spoken language.

Gesher School embodies the notion of communication as a basic human right and that all students attending the school, despite their level of need, will be allowed the tools to interact and communicate with the world around them. Whilst Gregory’s communication journey is still in its early phases, he is a clear example of how, in just a short period of time, a highly tailored and therapeutic learning environment allows our students to thrive.

* “Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is a range of strategies and tools to help people who struggle with speech. These may be simple letter or picture boards or sophisticated computer-based systems. AAC helps someone to communicate as effectively as possible, in as many situations as possible.”

Communication Matters

https://communicationmatters.org.uk/what-is-aac/overview/