Faith, Education and SEND: The Forgotten Sector

Sarah Sultman

Lost in History: Since the 1990s there has been a growing debate, both inside and outside academia, about the role faith schools should play in a 21st-century education system and whether or not they should exist at all, with strong and divided opinions both for and against. And within this politically and religiously charged debate, there has been a distinct lack of consideration given to the SEND perspective.

In the UK, policy still does not permit the creation of SEND faith-free schools and when challenged or asked why this is, no one we have met on our journey in the creation of Gesher has been able to give a satisfactory or justified answer — other than to agree that this is indeed the statute. Today in the UK 35% of state-maintained schools are faith-based whilst ‘almost all’ (with no definitive numbers published) private independent schools are aligned to a faith but not necessarily practising faith.

Google ‘SEND faith schools in the UK’ and no list will pop up.

The development of faith schools in the UK is historic, from when cathedrals and monasteries began providing an education to boys who were to become monks and priests in the 6th century, whilst the first schools for children, ‘blind and deaf, epileptic, and mentally and physically disabled’ were only legislated for some 1500 years later, in 1918. For many centuries, those with SEND were not deemed worthy of a formal, or even informal education, so it could reasonably be argued that the lack of consideration given to the SEND faith education community is a symptom of the immaturity of the SEND education system as a whole.

Parents and schools today are thankfully, in general, far more aspirational for their SEND children. Inclusion and neurodiversity have become part of our everyday vernacular and our attitudes and ideas around SEND education are continuously evolving. We are still learning much about how best to differently educate those who are differently able, yet to date, the faith element simply has not been factored in. Seemingly, this group within our society has, at best, been ignored, or it has been actively decided for them that faith does not or should not play a role in how we educate SEND pupils.

There is the old African saying that ‘it takes a village to raise a child’. For those with SEND that village is incredibly important. It extends beyond the school gate to the institutions, places of work, places of worship, and welfare systems in the communities that a young person grows up in. Yet there has been very little research done on the intersection of faith, SEND, education and community with no empirical data freely available on how SEND students feel and relate to their faith, how faith impacts their identity, how it shapes and contributes to their everyday lives and whether they and their families feel that a faith-based education is beneficial for them.

Culture and Community Values Matter

No doubt this is a complex area of study and differing cultures and faiths will have different attitudes and views towards their SEND populations. At Gesher, our Jewish religious perspective informs the type of Jewish culture, ethos and core defining principles of the school. Learning about one’s faith is not only concerned with developing the pupils’ knowledge and understanding of each aspect of their Jewish Heritage but also with developing their love for and commitment to its laws and practices, which include moral and ethical teachings and values. With this ideology at the forefront of our curriculum, Jewish Studies is taught at Gesher not as an academic subject, but as a way of life.

I think it’s been the making of her… without it, I think she would feel quite lost.. it’s become her safe space.

Parents Appreciate its Value

Ron Berger said ‘As a faith-based school, everyone who chooses to send their child to Gesher knows that there is more to life than academics. There is the human character of who you are as a human being. You choose to send your child to a faith-based school because your faith and your culture is something that matters to you because you want your kids to embrace values that you care about. And those values mean being a good person.’

For one parent, who knew that her son’s Jewish identity was important to him, it was a key factor in looking for a school. ‘It’s one of the reasons we chose Gesher in the first place. Because he enjoyed the Jewish side of things, we wanted somewhere that would meet his needs, and also meet his religious beliefs as well.’ For another parent, the faith element of the school, whilst initially seen as ‘a nice incentive’ rather than a non-negotiable, has come to be considered a crucial part of her daughter’s education. ‘I think it’s been the making of her… without it, I think she would feel quite lost.. it’s become like her safe space.’

The value of community permeates throughout the school and informs a large part of our practice. At Gesher, whilst we celebrate the individual: “…for the mind of each is different from that of the other, just as the face of each is different from that of the other.” (Talmud Brachot 58a), being part of a community means looking out for others, taking responsibility for each other and coming together in unity as a collective: “do not separate yourself from the community” (Hillel).

The power of community transforms the individual and at Gesher, we actively foster community amongst the pupils, the staff, our local Jewish community, the wider Jewish community and the world in the form of Tikun Olam which literally means to repair and improve the world. This concept shapes many of our programmes around social justice, giving to others and caring for our environment. We view school as just one of the structures that supports the young people that attend, so we must recognise that we do not operate in a silo, and the measure of our pupils’ success should not be in isolation. Rather it is our responsibility to understand the communities from which our students come and to work with them.

In a recent discussion with parents, the topic of community was featured as an important factor. All parents, regardless of their religious orientation, spoke in a similar way about what it was like being part of the school’s Jewish community. One said, ‘You feel you’ve got a family, it’s an extended family, you know you are all in it together.’ It would be an oversimplification to suggest that this is exclusively down to the religious orientation of the school but it does certainly contribute greatly to a feeling of belonging that extends beyond the school gates. Other unifying factors, such as parents’ collective experience of having a neurodiverse child are undoubtedly also at play. However, within the discussion around the theme of community, parents regularly mentioned the role that religious festivals play in building and fostering this feeling. Talking about last year’s Passover celebrations, one parent said, ‘You feel involved… everyone [children and parents] is experiencing it together’.

For many, faith matters. For SEND young people too. They will need support to access the texts and tenets and practices and celebrations of their family’s and community’s faith so that inclusion for them is meaningful and supportive. It is a part of their learning and they have learning needs that we should strive to meet.

End Note: To quote Lord Rabbi Sacks: ‘Children who are confident in their identity, know their people’s story, are familiar with its literature and at home in its practices, understand their responsibilities to the wider society and practise the values of tzedakah (charity) and chessed (kindness) are at peace with themselves and with the world. They become a credit to the Jewish people and an asset to Britain. We can ask no more; we can do no less.‘

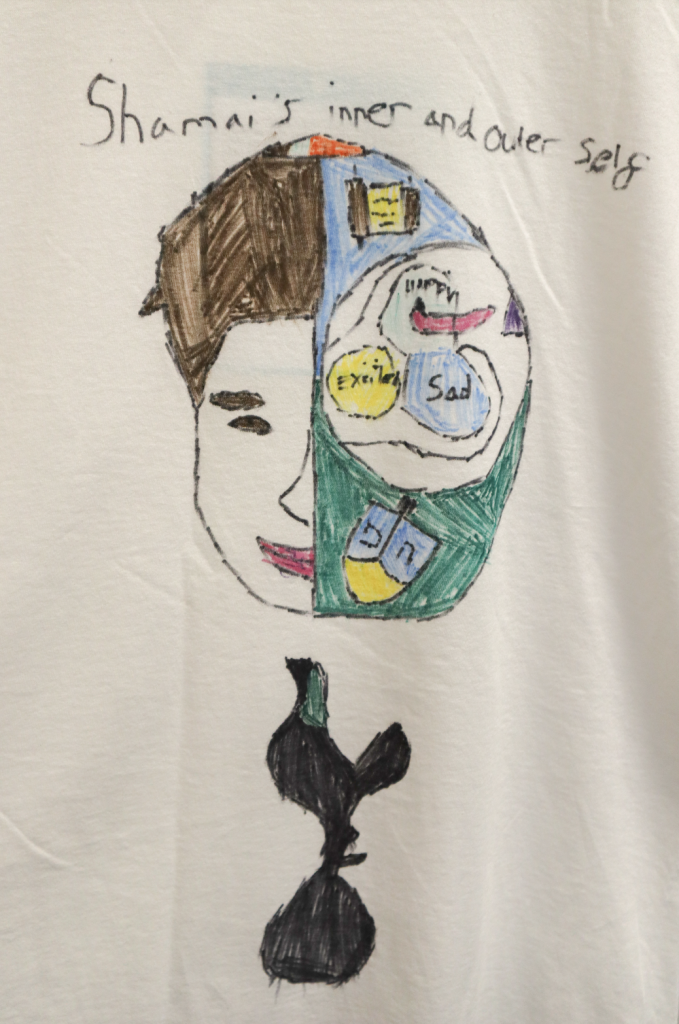

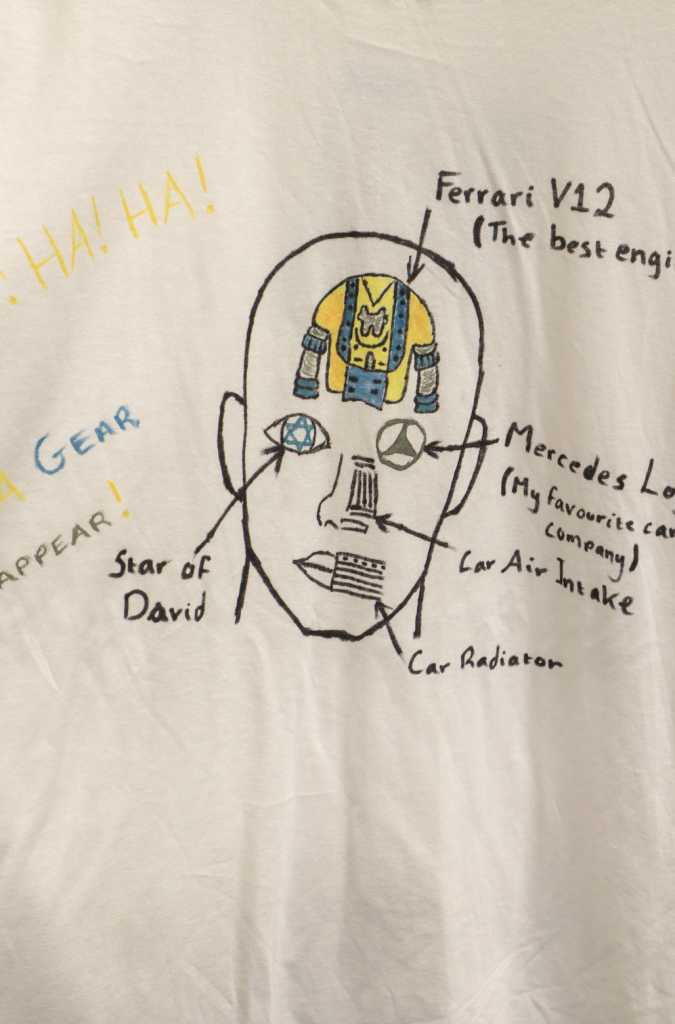

In one recent school project our year 8 students were asked to design a T-shirt which conveys their identity. What makes them who they are? How important is their name? What are the influences that shape their character? For these particular students, faith proved relevant to how they view themselves and contextualise themselves in their world at large.

For my T-shirt, I have made a design which shows my outer and inner self. My outer self is what people see when they look at me, I have drawn a self-portrait of half of my face. I have brown hair and when I am happy, this shows on my face by having a wide smile. My inner self and the other half of my face is a football as well as my future career as a footballer. Inside the ball, I have written the emotions I feel most on the inside which are happiness, excitement and sadness. I also added feeling nervous as this is how I feel before I play a football game. I have also drawn a Kippah, dreidel and Torah as this represents my Jewish identity which is very important to me. — Shamai (Year 8)

My inspiration for this project was to focus on what my passion is and to me, that’s cars. Based on this, I split my face in two and used one half to show how people see me on the outside and the other half to show how I like to be seen by the world. I did this by replacing some of my facial features with my favourite parts of a car. Also, I replaced my brain with a twin-turbo V8 engine representing the power of thinking. As well as cars, I’m very passionate about making people laugh. Coming up with jokes is one of my favourite hobbies and I can make my friends feel better with my jokes whenever they’re hurt or feeling sad. To show this, I gave myself a big smile and added a ‘HAHAHA’ over my head. Being Jewish is a very big part of my identity and it is something I am very proud of so I drew a star of David in the middle of my eye to show my unique Jewish perspective on life. This piece represents my favourite parts about myself and shows everyone what makes me, me. — Ariel (Year 8)

Professional Prompt Questions

Having read this article, what benefits are claimed from having a unifying faith, culture and belief system (across school, family, community)? How might a non-faith-based school generate an equivalent sense of unity?

What arguments might you make that there should or shouldn’t be faith-based SEND schools?