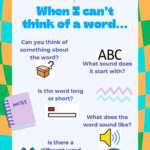

A word-finding difficulty is when a person knows and understands a particular word, but has difficulty retrieving it from their brain to use in their speech. This is similar to how we sometimes feel something is on the ‘tip of our tongue’. Children might not able able to find the word at all, they might retrieve a word that sounds similar to the one they want or they might produce a nonsense word. Check out this website to learn more about the signs that indicate a word-finding difficulty and how you can help support at home. The linked document below also contains prompts which we use at school to help support retrieval of the word they are looking for.

Ever seen ‘Blanks Level’ written in your child’s PLP target or annual review report? This refers to a language model which we can use to map and model understanding and use of abstract language. There are 4 levels which go from talking about things directly in front of you to talking about abstract ideas. Below is a video, plus one of our resources.

Gesher’s Guide to Blanks Questioning

There are two ways in which we may learn language: ‘Analytical’ processing and ‘Gestalt’ processing. Typically we think of language development as learning single words and building them up to full sentences – this is called analytical processing of language. Gestalt Language Processors on the other hand, will start by using whole ‘learned’ phrases, progress toward using single words, and then build their back up to more functional and ‘spontaneous’ phrases. Understanding which way our children are learning language will not only help us to understand them more effectively, but also help us to further support their development of functional communication.

Below you can find a video which explains more plus a link to one of our PDFs on the topic and a website which contains some top tips for parents.

We are delighted to announce that Gesher School have partnered with The United Synagogue so that we can work together effectively, to make Jewish Communities more accessible, not only for our Gesher children, but for all children and adults with additional needs. In line with this, we have appointed Rivka Steinberg to harness the expertise of Gesher School and share it with our communities, in the role of Lead Advocate for Additional needs. She will be spending her time both at Gesher School and the Finchley US office.

In a previous chapter of my life, I spent many years working in scientific research. My interest in improving the quality of education and health services for children with Special Education Needs and Disability (SEND), developed, when my eldest daughter was diagnosed with a physical disability in 2005 and with it the requirement to become a strong advocate for all her additional needs. I trained with IPSEA (Independent provider of SEND legal advice) to develop a strong knowledge of the SEND legislation and I have used my broad knowledge and skills gained over many years, to advise parent carers on SEND matters. I have also worked for voluntary organisations, specialist settings and parent advocacy with Local Authorities.

My personal and professional experiences have seeded a desire and passion to share the knowledge acquired in my own journey and to work closely with leadership in the community, to enable all children and adults, to lead a high quality of life, regardless of their additional needs. This is all about breaking down barriers so that children and adults with needs, are more fully integrated and supported to embody Jewish life in ways that are meaningful to them without feeling compromised.

It is no longer enough that we raise awareness outside of Gesher School, neither can we allow this vital work to be regarded within the framework of a charitable agenda. Rather we need to actively share Gesher’s expertise and resources so communities will make room for difference, engaging wholeheartedly in access and inclusion work, so that children and adults will be enabled in all facets of Jewish community life. It’s about seeing the ‘ability’ in Disability.

I am very excited to be part of Gesher School and to really make a difference as the Lead Advocate for Additional Needs. Some of the projects we are looking at include:

- Supporting the preparation of Inclusive services, Chagim, sessions and events

- Sharing strategies, resources and tips

- Engaging more members and families in US.

If you have any suggestions or you would just like to be in touch with me directly then please do reach out to me at [email protected].

Reimagining Assessment: Views From an Autistic Young Person

Joshua Gross

Since the 1990s, the way we assess young people has been dominated by a culture of public accountability and competition, leading to the unhealthy belief that the grade is everything. The idea is now so important that many exams, like GCSEs and A-Levels are referred to as “high-stakes” tests because of the way they determine the next stage of someone’s life.

Those who create the high-stakes assessments claim that they are the fairest and most rigorous tool we have to demonstrate student achievement. However, the evidence used to back up these claims is often insubstantive (Richardson, 2022). One of the consequences of these high-stakes assessments is that young people’s outcomes are reduced to a number or letter which only reflects a very small proportion of their experiences and achievements at school and usually only in academic subjects.

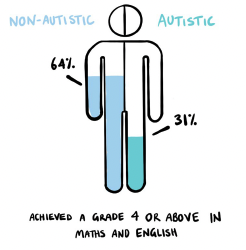

Whilst this affects all young people, data has shown that, on average, autistic young people do not achieve the same levels of academic success as their non-autistic peers assessed in this way. The most up-to-date government data shows that 64% of non-autistic students achieved a Grade 4 or above in Maths and English, compared to 31% of autistic students – and this data is not a one-off. The same pattern exists in the previous three years’ data. While the statistics alone are striking, even more profound are the hidden stories behind the data. As such, in this piece, we share the reflections and experiences of Joshua, an autistic young person who has the lived experience of feeling let down and misrepresented by the current system and who has vital ideas on how it might be reimagined to prevent the same thing happening to others.

“The big problem with existing assessments is that they are the be all and end all when you leave school.” Joshua

The same idea is expressed in the opening sentence to this article and yet what this means for young people can often get lost in the statistics. For Joshua, who at the time of writing is applying for apprenticeships, the implications are clear.

“I can only put my grades, not the fact that I spent most of my A-Level time suffering through extreme mental health issues and that it was a miracle I even made it to sit the examinations, not the six times I almost dropped out and came back to them later… It becomes really difficult to come out the other side and still be a strong candidate when the only important thing is what grade you got.”

Joshua’s solution to this problem would be for schools to recognise the skills that young people have through a more flexible approach to curriculum and to assessment. In Joshua’s case, he has a talent and passion for computer programming and, while he was able to take this as an A-Level, he was still assessed within the constraints of that curriculum and the conventions of exams.

“In my A-level computer science class we had people who had never opened the Python Editor before and we had people like me who had made full video games in one day before… I would be running off doing these ultra-complex things at home that would never be recognised because they weren’t even remotely related to the curriculum. Like, I can make a video game using languages that the curriculum doesn’t even know exist. And I’m just sitting there doing these things, but none of them get recognition. I can do all this stuff and it doesn’t matter because it wasn’t what I was told I had to do. I didn’t fit that specific guideline and therefore it’s not good enough.”

By having a curriculum that is less constraining, less of a rule book, there would be more scope for teachers to work with young people in their area(s) of interest and strength, aligned with their passions. While this would have benefits for all learners, there would be particular benefits for some autistic young people who often have a special interest or aptitude. Recent research by King’s College London, for example, has shown that when adults are accepted as having a special interest, and where it is responded to positively, recognised and valued, this can lead to them excelling in the linked curriculum area (Wood, 2021).

As not all neurodiverse young people will have a special interest that can be assessed within school, it is also worth considering other ways in which a more flexible assessment process would be beneficial. Here, Joshua has further important ideas to share.

“Assessment as it is now is not actually really a test of knowledge, but more a test of memory. I found often that those kinds of assessments really did not work for me, but one that I really excelled in were the two B-techs that I took in Business and Digital Media. Instead of having this one assessment that you’re building up to and studying in unhealthy ways for, you’re working on it throughout the entire course. It’s not one giant thing, it’s a bunch of smaller things. Break one big problem down into a bunch of smaller ones, and suddenly it becomes less of a big problem.”

Joshua’s views about coursework are echoed in the academic literature, which has shown the pedagogical benefits of such forms of assessment, as well as the fact that students prefer it to exams (Richardson, 2015). Despite this, under the current assessment system in England, none of the Maths, English or Science GCSEs have a coursework component which counts towards a student’s final grade. As such, the work that a student does across two or three years of study is condensed and assessed through a few hours of exams. This in turn then shapes their future opportunities. Joshua considers this system to be a particular challenge for autistic young people as “Often the pressures of the school system can break a student so easily and so quickly. And it becomes really difficult to come out the other side and still be a strong candidate when the only important thing is what grade you got.”

There are two more things that we know about the lack of fit between the current assessment system and neurodiversity. One was well articulated by Joshua: “If you emphasise ‘standards’ and ‘standardisation’, then by definition this will not work for autistic young people who are, by definition, non-standard.” The other, which is linked, relates to the idea of “spiky profiles”. Autistic learners are less standardised, less conventional – they have great strengths alongside different challenges. An assessment model that emphasises the challenges (e.g. writing essays) and minimises the strengths and passions (e.g. technical capability, creativity) will serve both autistic youngsters and the system badly.

Endnote

Joshua’s views are those of just one student, but the dearth of autistic voices in both the academic and non-academic literature in this field makes this a provocative contribution and one that we hope is built on by further activity in this area.

References

Richardson, J. T. (2015). Coursework versus examinations in end-of-module assessment: a literature review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(3), 439-455.

Richardson, M. (2022). Rebuilding Public Confidence in Educational Assessment. UCL Press.

Wood, R. (2021). Autism, intense interests and support in school: From wasted efforts to shared understandings. Educational Review, 73(1), 34-54.

Professional Prompt Questions

What rings true for you in Joshua’s comments?

You will almost certainly have neurodiverse learners in your school. Might a small piece of research or a focus group with them help to unearth challenges they face to which you could respond?

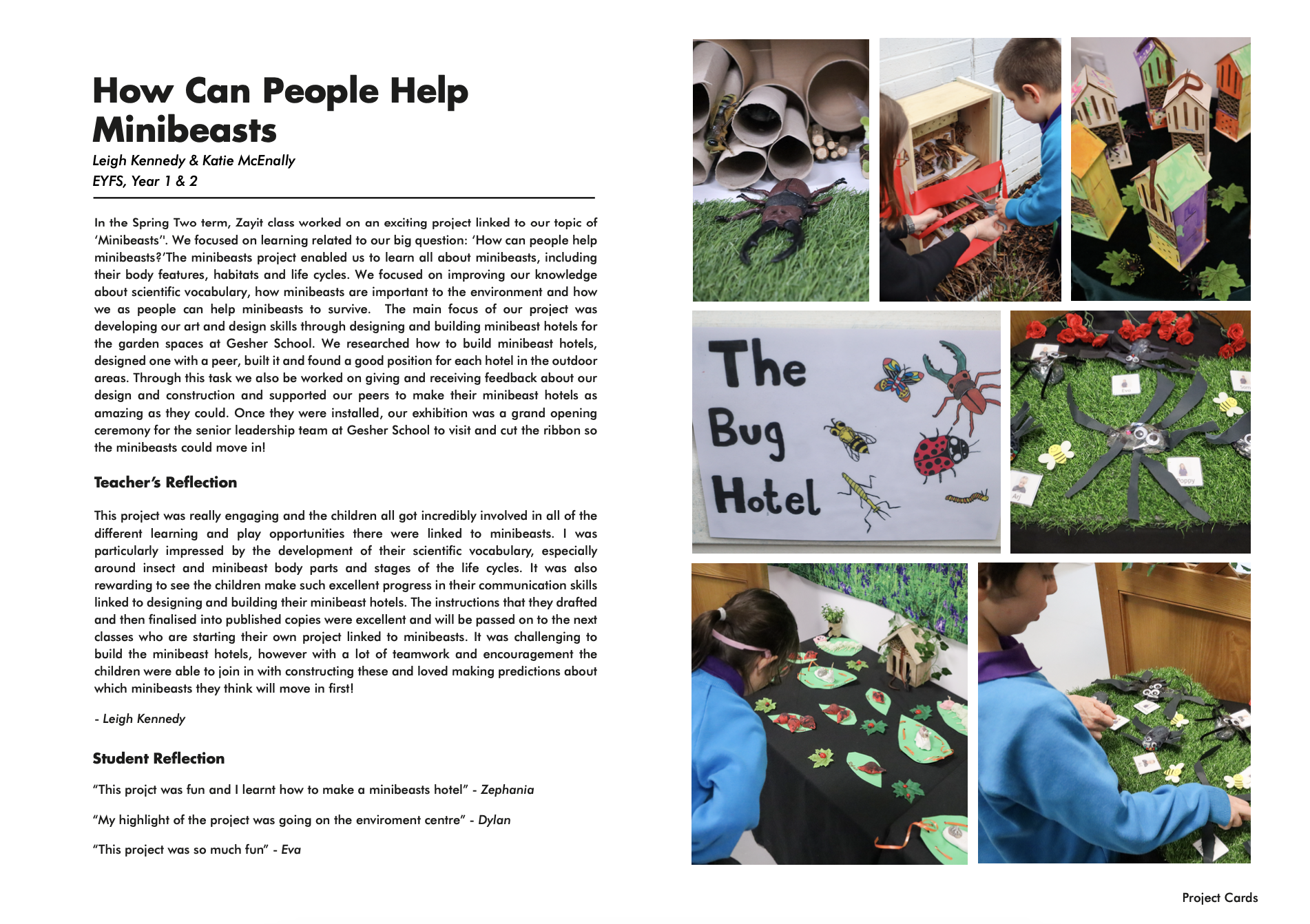

In Spring Two, Zayit Class worked on an exciting project linked to their topic of ‘Minibeasts’, They focused on improving their knowledge of scientific vocabulary, how minibeasts are important to the environment and how people can help to protect them.

The main focus on their project was to develop their art and design skills by designing and making minibeast hotels. Through this task the students also worked on giving and receiving feedback about their designs.

The exhibition for the project involved Gesher’s Senior Leadership Team cutting the ribbon as part of the grand opening of the hotels.

Teacher’s Reflections

- Engaging with all children involved the different learning and play opportunities

- Rewarding to see all the children make great progress towards their communication targets

- Challenging to build the minibeast hotels, however with a lot of teamwork and encouragement the children made great progress

Students’ Reflections

My highlight of the project was going to the environment centre.

The project was fun and I learnt how to make a minibeast hotel

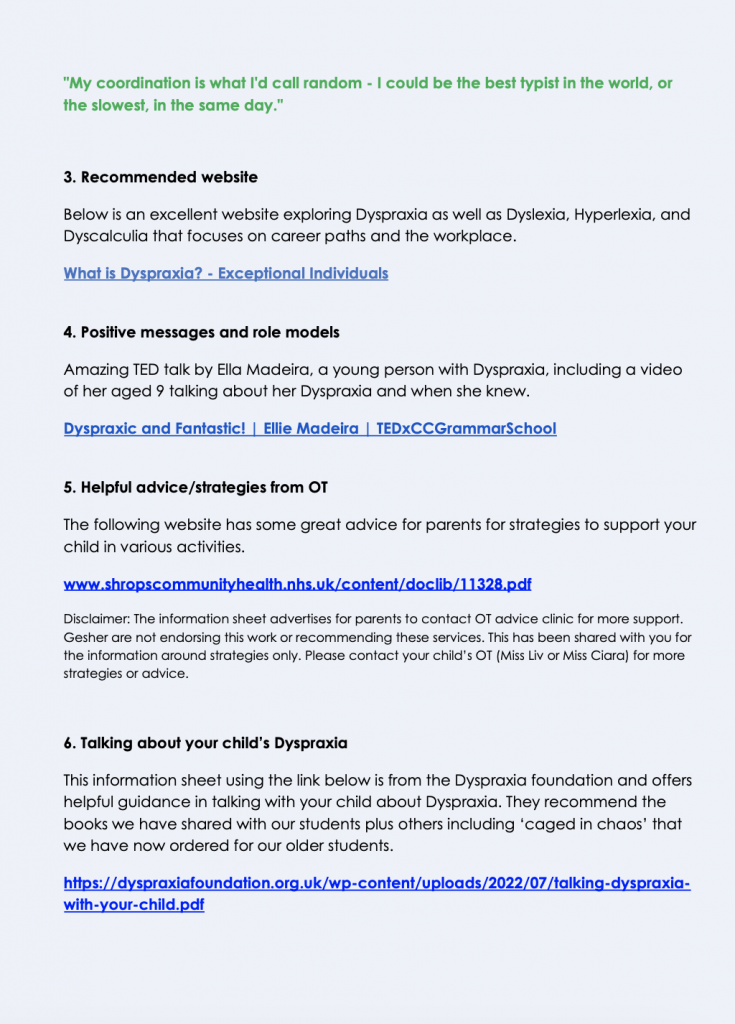

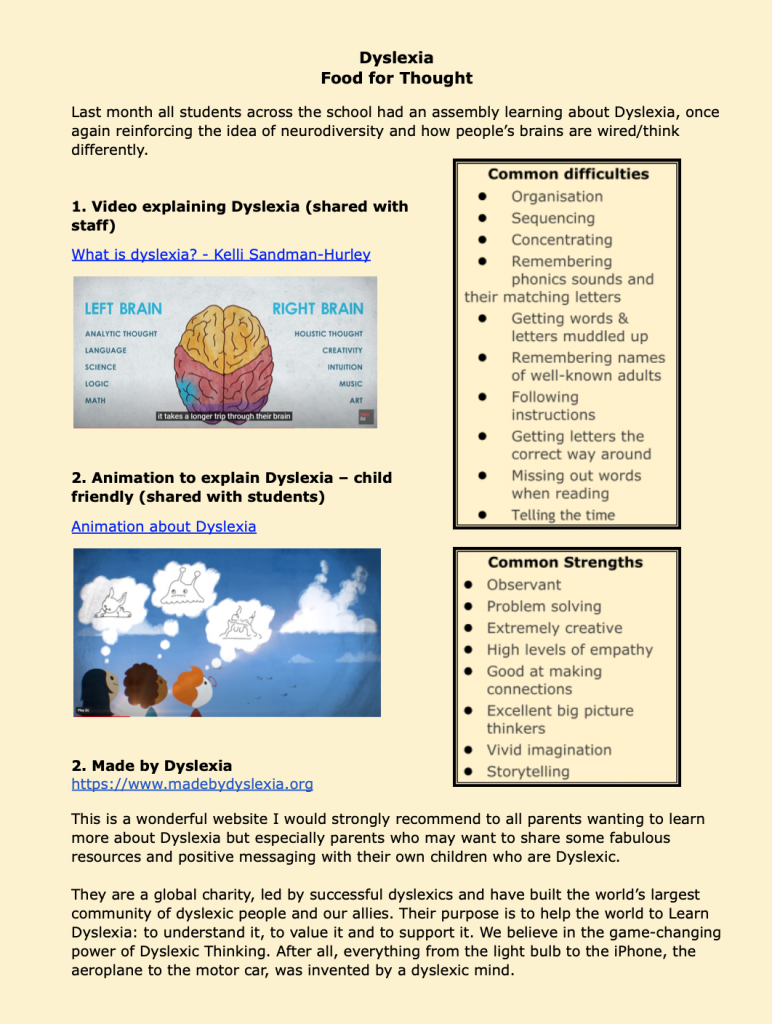

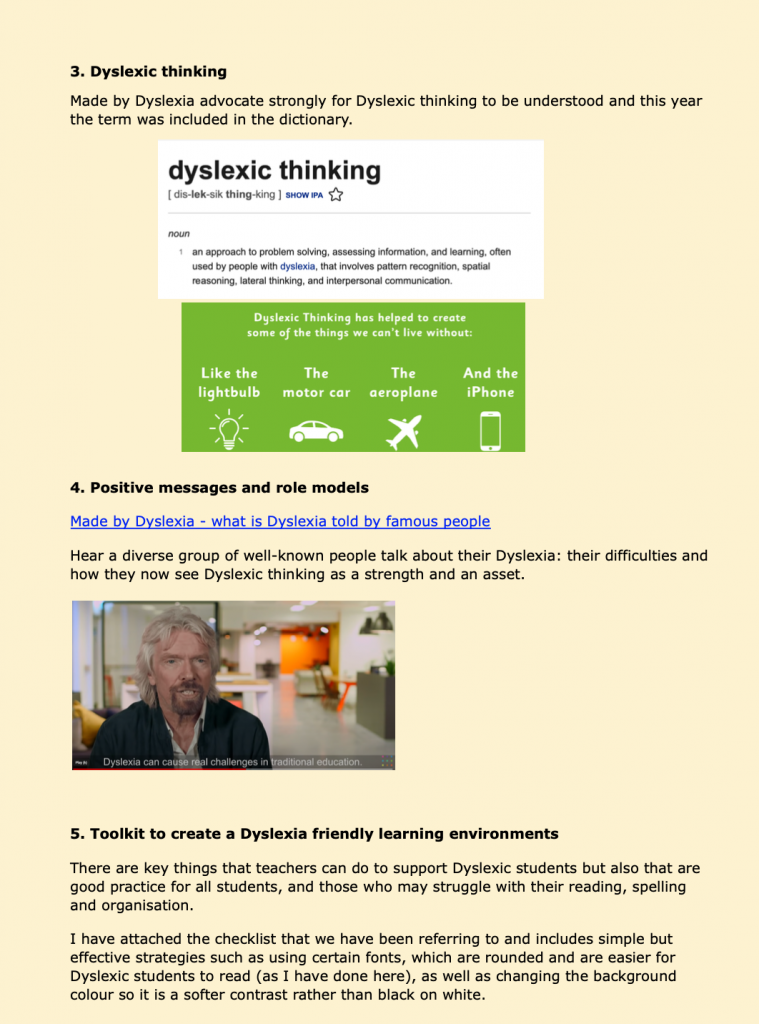

Top Tips for Dyslexia-friendly Learning Environments

- Backgrounds – Change your smartboard backgrounds and/or font colour to another colour to make it easier for everyone. If you have a child who already has a preference, use that, otherwise, opt for a whole school colour. Light blue is a popular choice.

- Books and overlays – Some pupils may find it easier to write in books with coloured backgrounds and have a coloured overlay.

- Dyslexic-friendly fonts – There are fonts specifically designed for dyslexia that everyone can read. https://opendyslexic.org/. Alternatives are Ariel, Comic Sans, Verdana, Century Gothic, Tahoma, and Calibri.

- Visuals – All children benefit from visual processing. It improves retention and supports retrieval. We do this well and know to use a range of visuals.

- Graphic organisers – Graphic organisers are fantastic to support learners’ thinking, processing, understanding and organisation. This includes using writing frames, but also mind maps and flow diagrams.

Try this link for older students where you can sign up for free https://www.mindomo.com/ or to create simple to more complex ones for all students: https://www.canva.com/graphic-organizers/templates/

- Speaking – ensure we are breaking down information into smaller chunks.

- Don’t ‘pick’ on them to read – This can be seriously demotivating and traumatic in a whole class situation and may be detrimental to their reading progress. They can read to you on their own or with a trusted peer at any time.

- The usual strategies – Such as natural brain breaks to avoid cognitive overload, memory aids such as word mats, a clear line of sight to the teacher and a seat close to the front to aid non-verbal communication.

- Mark positively – Start with what they can do and build on that. You don’t want to stifle amazing ideas on account of worrying about grammar and punctuation.

- Spelling – if students can’t spell a word, spell it aloud for them, and at the same time, write it on the board – provide key spellings for them to refer to. You can also use the RWI sound board so students can ‘try out’ spellings with alternative phonemes (ee, ea, etc). If using the computer, having the spelling and grammar aids on is good!

- Limit the copying they have to do – give them copies of the learning that they can have in front of them and present with appropriate fonts, backgrounds and sizing in manageable chunks.

- Technology – Explore advances in technology with your dyslexic learners. Is there a use for a reading pen, a smartpen or some text-to-speech software? Microsoft accessibility has many free features to explore. When using chrome books or iPads, there is accessibility software available with fantastic programmes such as ‘Immersive Reader’.

Pupils with dyslexia also have skills such as a strong memory for stories, a wonderful imagination, great spatial reasoning and can think outside the box! You can find more details at Dyslexia Help.

Creating Better Schools by Design

David Jackson

Ask most people to draw a house and nine times out of ten the house they imagine will be a square box, with four square windows, a pitched roof with a chimney, and often some smoke curling into the sky.

We share a mental model — a blueprint — for what a house is and should look like. We don’t stop to wonder:

- Does our house have to be square or could it be a different shape?

- Should it be one storey high, or two, or three?

- How many windows of what size should there be, really?

- What purpose does the chimney serve?

Our shared ideas about schools are fixed in much the same way.

There are variations, but our mental model for school tends to include classrooms, corridors, rows of desks, students grouped according to age, one-hour lessons, subject teaching, tests, and so on. This model is based on schools designed in the past. We don’t stop to question whether the school, which we are after all drawing in the C21, should be — needs to be — very different from the blueprint created decades ago. We might ask:

- What ideas about learning are informing the layout of our school? What might classrooms look like if we thought of them as places where great learning can happen?

- Does all learning need to be packaged into ‘subjects’?

- Are one-hour lessons the best unit of learning?

- Is one teacher with 25 students better than two teachers with 50 students?

- Why are all students assessed at the same time when they mature differently?

- Do we have to assess by written exams emphasising memory?

… and so on.

Designing a new school for real is a chance to ask questions like these, and to ensure that the new school is more than just an improvement on the existing model.

“Gesher undertook a serious school (re)design process that placed the needs of their students at the heart of decisions about their new school design.”

At Gesher School, staff, students and parents know how badly a change to the model is needed because most of Gesher’s learners have struggled in schools like the one most of us would draw. So, Gesher undertook a serious school (re)design process that placed the needs of their students at the heart of decisions about their new school design.

Gesher was transitioning from a highly successful primary school to becoming an all-through learning community and needed to find a new school building and facilities, recruit staff, create a secondary school curriculum and reframe its mission and identity.

The leaders of Gesher School knew they needed to go way beyond improvements on the existing model, to design a whole new way of thinking about and doing school, in ways that learned from and built on their experience with primary-age children. They asked:

How might we design an all-through school that will offer success, enhanced self-esteem, personal efficacy, and progression opportunities for all our young people?

Secondly, in doing so, how can we involve multiple stakeholders in our design process?

Thirdly, how might we stand on the shoulders of existing practices around the world?

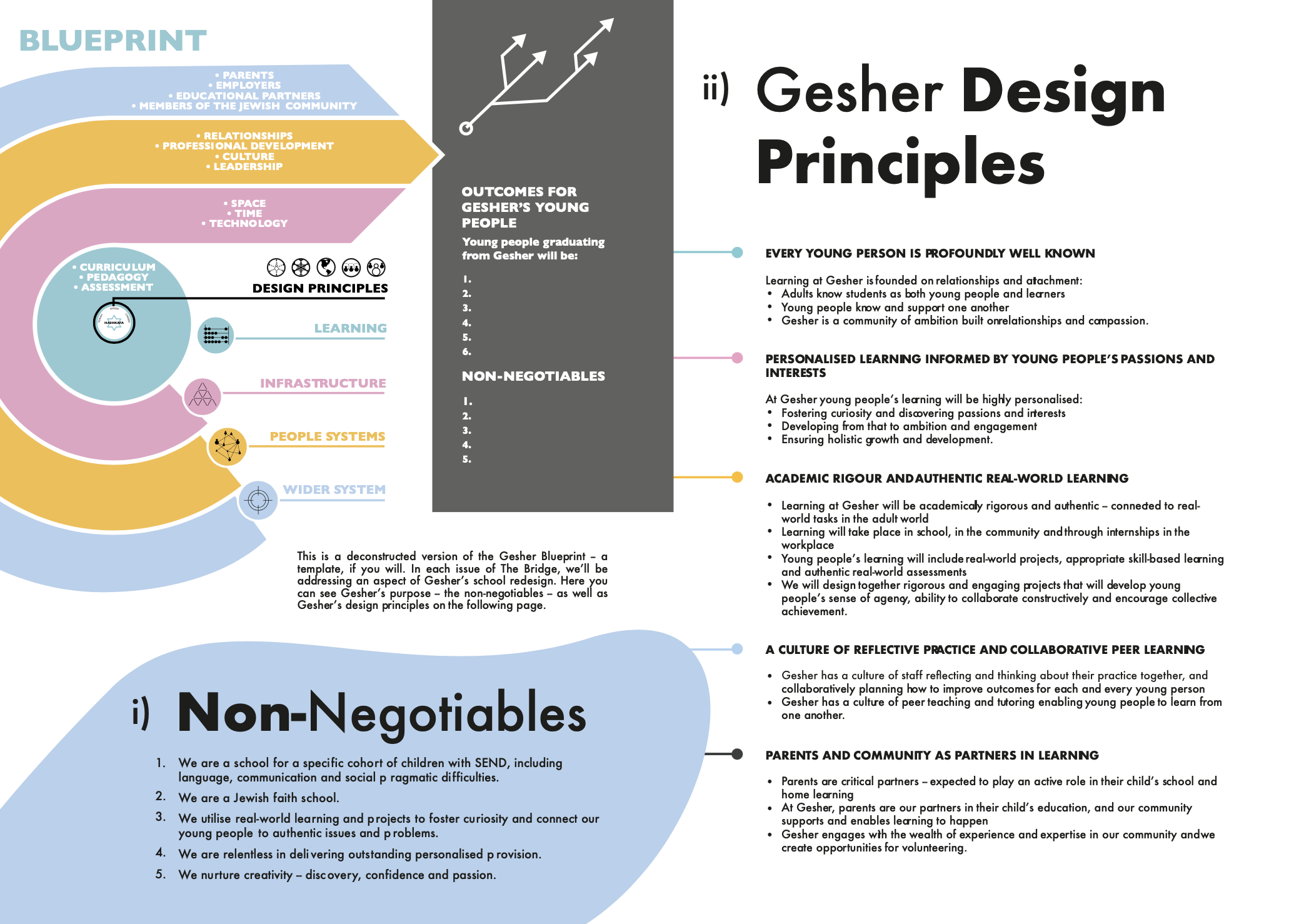

The design process that Gesher School entered into comprised eight workshops, each involving different stakeholders, which resulted in a school blueprint for:

- A bold vision and purpose; and

- A set of values-based design principles; which were

- Brought to life in plans for a range of innovative features that add up to a very different kind of school.

Upwards of 100 school staff, parents, students, community members, and other local stakeholders contributed to this seriously intentional and inclusive school design process.

Each issue of The Bridge will address an aspect of Gesher’s school redesign process. This issue focuses on the first two of the eight school design workshops that Gesher School undertook, which concerned (i) purpose and (ii) design principles.

(i) Purpose

Gesher’s discussions about purpose started with identifying their ‘non-negotiables’. Non-negotiables tell everyone what is and is not on the table; what is and is not within the scope of the school design team to change. Examples might be ‘no selection by ability’ or ‘the school will be co-education’ or, in Gesher’s case:

- We are a school for a specific cohort of children with SEND, including language, communication and social pragmatic issues.

- We are a Jewish faith school.

- We utilise real-world learning and projects to foster curiosity and connect our young people to authentic issues and problems.

These clear non-negotiables influenced design features relating to Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) provision, to faith observance and understanding, and to the design of curriculum and pedagogy.

A further key defining issue for Gesher to articulate was purpose – the vision and outcomes to which the school community would aspire. Being clear about what the school had to achieve with and for students; about the purpose of learning; about what matters for the community of the school — staff, students and parents – was an essential bedrock of the design process.

Within the current system, aiming for good examination outcomes is a given, and if that was all that mattered, then job done. However, during the workshop, through extensive discussion – and many post-its – it became clear that exam success on its own was not nearly enough. In brief, the outcomes Gesher agreed are that young people should become:

- Skilled for the future workplace

- Qualified for the next stage (exam results plus)

- Independent learners

- Confident in their sense of self

- Builders of meaningful relationships

- Ethical and responsible citizens.

These, one might hope, could be purposes shared by most if not all schools, but two things qualify them as exceptional in Gesher’s context. The first is the inclusiveness of the intent. They are purposes for all students, regardless of their prior educational history or unique needs. The second is to remember that Gesher is a school for children with identified SEND needs, most of whom have been unable to thrive in mainstream schools.

“Staff engaged with mini-case studies of interesting and successful schools around the world to draw from them the particular design features that inspired them.”

(ii) Design Principles

Workshop two was exclusively concerned with design principles and involved staff at the school considering the question: What would be the design principles or features of a school that can confidently achieve these outcomes for all its learners?

Staff engaged with mini-case studies of interesting and successful schools around the world to draw from them the particular design features that inspired them. They used this as a basis to shape their own, then tested the resulting principles they created together using personas of children at Gesher, asking: Would this work and how would it work for Amy or Peter?

Next Time — Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment

Agreement on these three components — the non-negotiables, purposes and design principles — precedes work on designing the more practical features of a school. Clear purposes provide a constant reminder of exactly what we aspire to achieve with and for learners and their families. Design principles provide the guiding architecture that relates to these purposes. They are ‘laws with leeway’ that frame what we do and how we do it. They are also the features that unify and inspire those who work in a school, and they guide and discipline decision-making.

With these three in place, the design process moves to consideration of the curriculum, pedagogy and assessment practices that will be informed by and consistent with the design principles and which will enable every student to achieve the outcome ambitions. That is for next time.

Designing New Schools in the USA

In America, there is a long tradition of creating new school designs. Some of the most successful schools in the world have been created in this way – Expeditionary Learning schools; High Tech High (some of whose resources we share later); Big Picture Learning schools; New Tech Network are all examples. The Gates Foundation alone funded more than 2,500 ‘small school models’ across the United States, and New York alone has 200.

Not all of these new school models have been equally successful, of course. However, their students consistently outperform their peers in conventionally sized and structured high schools with comparable demographics. There are some common design features across the majority of these models — and they are very different from the conventional UK school — they all:

- Focus on the centrality of relationships and personalising learning — have ‘advisory’, where advisory is the soul of the school, symbolising relational support for students

- Include project-based learning, an engaging and empowering pedagogical model, which also requires teachers to collaborate as designers of learning

- Have a pervasive cultural identity and school-level ownership of what matters, including what is assessed and how and by whom it is assessed

- Facilitate powerful and sustained adult learning.

The Cost of Not Having New Models in the UK…

Not to foster innovation in school design means that we constantly focus on striving to improve the existing school model – a model more than 100 years old and out of date.

It is a model with multiple features crying out for redesign. For example, it has failed to achieve equitable outcomes, or to address socio-economic challenges, or to engage disengaged learners — or to fully engage most learners, for that matter. Nor has it provided teachers with an intellectually challenging profession, or excited and involved parents around the experience of their children.

Professional Prompt Questions

The design process described above is effective applied to existing schools as well as new ones — revisiting purposes and design features together as a prelude to reviewing wider practices. Might this have value for your school?

The review detailed above distilled six clear outcomes that Gesher is committed to evidencing for all learners. Does your school have similar clarity about its purposes?