Reimagining Schools By Design: Assessment, Pedagogy and Curriculum

David Jackson

Teaching: the design and facilitation of great learning through relationships

This short article is about the second phase of the process Gesher School undertook to design the curriculum, pedagogy and assessment they knew they would need to do a brilliant job for children who learn differently, as they moved from primary into their secondary education; from childhood into adolescence, from primary to all-through.

The ‘school design lab’ process – eight workshops involving about 100 stakeholders, completed in March 2021 – resulted in a blueprint for this new school ambition. You can see the final version of the Gesher School Blueprint here: https://gesherschool.com/about-us/blueprint/.

It is worth looking at – for its comprehensiveness, its ambition, its philosophical coherence and the obvious seriousness of intent. Beyond that, there is much to recommend in the evident way it unites a school community (internal and external) around a shared mission and sets out the practical requirements needed to achieve this.

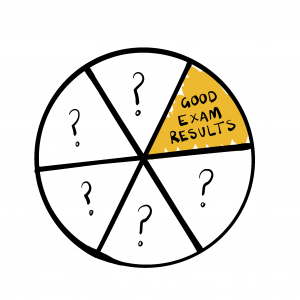

The process to develop the blueprint began by asking “What outcomes do we want all our learners to achieve?” We started with a pie chart (six slices), one of which already had “good exam results” filled in, as a given. The task then is to populate the other five slices. (It could be six slices saying “good exam results” if that’s the only outcome that matters – but in a decade of doing this activity, exams have never featured more than once.) The result? Agreement about the purpose of the school and the outcomes for all learners that matter to the school community.

Standing on the shoulders of giants

Having agreed purpose and outcomes, the next stage in the process was the development of a set of design principles to achieve these, which form the values and practice architecture – the “laws with leeway” – for the school. In that process the Gesher team engaged with the designs of highly successful schools around the world, in a process known as horizon scanning, to find inspiration and ideas that would help them to learn from the very best that exists and has evidence of success.

You will find more on the Gesher school design process in The Bridge Issue 2.

Having the purpose, outcomes and design principles agreed upon, the next couple of workshops focused on assessment, pedagogy and curriculum.

Assessment

The Gesher Blueprint, then, sets out the school’s desired outcomes. They include: skilled for the future workplace; confident in their sense of self; builders of meaningful relationships; and ethical and responsible citizens. Finding meaningful ways to assess, recognise, accredit and value these – to validate them – is the next stage in the design challenge.

Another desired outcome is qualified for the next stage, and while existing accreditation pathways can obviously fit that bill to an extent, they don’t get close to assessing “meaningful relationships” or “confidence in sense of self”.

Fortunately, there is a different audience for some of these outcomes – the students themselves, their parents, peers, community members, etc – and there are known ways of doing it. There are exhibitions, digital badges, portfolios (real or digital), records of achievement, transcripts or even a unique, composite and personalised School Diploma owned and endorsed by all stakeholders, incorporating a range of such validation methods.

Professionals generally agree that schools should be free to assess what they value, rather than driven to value what is assessed. Gesher’s Blueprint states that it will generate unique profiles… affirm talents… recognise unconventionally expressed achievements… and work of relevance to the community and the world. This ambition is shared by many schools and there are, as we have seen, a range of possible ways of assessing what is valued. However, few schools do. Gesher, in this respect – as in many others – aspires to be a “beautiful exception”.

Pedagogy

Ask secondary teachers about their professional knowledge-base and most will probably talk about subject expertise. This is not their professional knowledge-base: it is what they bring in service of their professional knowledge-base. Lots of geographers or scientists or linguists don’t teach.

Teachers’ professional knowledge-base is the design and facilitation of great learning through relationships. It is the creation of apt pedagogy combined with personalised knowledge and understanding of learners. In other words, teachers are designers. They create great pedagogical designs together.

Only, in most schools, they don’t.

To do this requires scope for interdisciplinary planning; it involves real-world relevant tasks (to make learning matter); it will deploy a repertoire of assessment methods (appropriate to the task, relevant for each person); and it requires time deployment that allows on-site and community learning. This is different from 25 one-hour lessons. It also requires that teachers have time together (to design together).

For Gesher, and for most of the astonishing schools around the world that were studied in the horizon scanning, Project-Based Learning (PBL) provided at least part of the pedagogical solution. Real links have been made with the professional PBL knowledge-base from High Tech High and Expeditionary Learning Schools as international examples and with XP and School 21 as domestic ones. Additionally, Gesher commissioned the support of Imagine If to help facilitate its journey.

Gesher, together with a number of other schools of course, deploys time and space flexibly (the subject of a future article); combines a core of subject teaching with flexible interdisciplinary learning opportunities (PBL); deploys a range of assessment approaches relevant to the task; and, because it is a SEND school (although all schools are SEND schools), integrates into learning designs therapeutic approaches and support.

And these rich approaches, whilst great for students, are also fulfilling for the professional lives of teachers.

Curriculum

If pedagogy is how we teach stuff and how learners learn it, and assessment, broadly speaking, is the range of ways we let students and other stakeholders know how well they are doing, then curriculum is simply the range of material – the content – we want students to learn.

For most secondary schools the curriculum is pretty straightforward: divide what we teach into “subjects” and have specialist subject teachers deliver it in lessons lasting about an hour. The learning week, for learners, is therefore a jigsaw puzzle of disconnected hour-long subject lessons (French, then PE, then English, then Science, then Maths….) and fragmented relationships.

There is another way.

Gesher’s curriculum statement emphasises “the application of knowledge through real-world assignments and projects… rooted in Jewish values… highly personalised and responsive to individual interests, aptitudes and needs”. Much is packed into those 24 words:

- Application

- Real-world uses

- Projects and assignments

- Overt values components

- Highly personalised

What all this means practically at Gesher is that the curriculum contains all the subject knowledge required, some of it taught as it has always been taught, but much of it designed into projects, with real-world relevance (perhaps real-world need) within which students express agency, personalise their contributions and also integrate or enact the values from relevant parts of their culture. They might be assessed in a range of ways, singly or in combination – tests, exhibitions, vivas, presentations, peer evaluation, portfolios, or whatever.

Endnote

The Blueprint design shows graphically that desired outcomes (purposes) frame everything and lead to school design principles facilitative of those outcomes. In other words, “Here are the things we want all learners to achieve and to do and so we need our school to be designed with features like this.”

The heart, the driver, the energy source to achieve this is the integrated and interrelated core of assessment, pedagogy and curriculum. Beyond that, there is a range of further features related to technology, time and space; culture, leadership and professional development; parental partnerships and community relationships.

More of that next time, perhaps.

Professional Prompt Questions

- If your school was to do the pie chart activity – the six outcome areas that really matter to you – what would be included? (You could try it as a staff workshop activity.)

- What scope is there in your school for teachers from different subject disciplines to plan learning together? What could there be?

- Do you agree with the definition of teaching at the start of this piece? If so, what implications might that have for your teaching or your school?