Click on the link below to find practical tips to support children’s wellbeing and behaviour:

https://parentingsmart.place2be.org.uk/

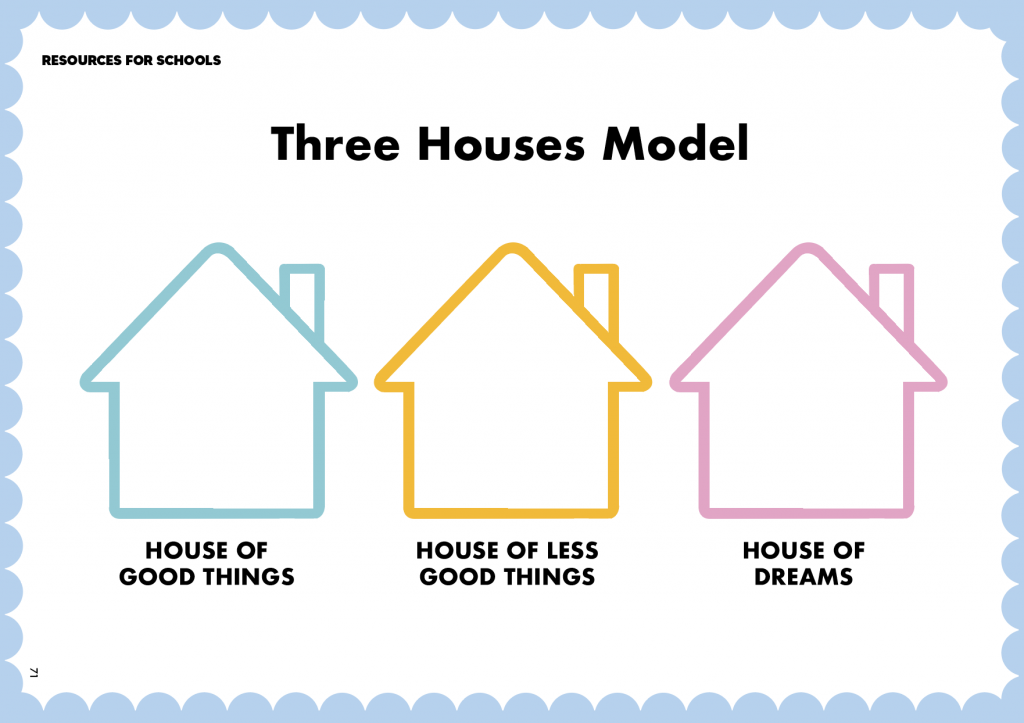

The Three Houses model is a tool which provides a visual way for people to express their views about a topic or experience. The tool was originally developed in 2003 in New Zealand for use in the field of child protection, but since then has been adapted for use with other groups. The version here is based on that created by Cunningham (2020) who used the tool as a way of eliciting the views of autistic children about what made their school autism-friendly.

How Does It Work?

The Three Houses model is a very flexible tool, which can be adapted to suit the needs or preferences of the young people you work with. Below are two options for how the tool could be used.

Option 1: The adult and young person draw three houses together. Once the houses are drawn the adult explains the name of each house: house of good things; house of less good things; house of dreams. The adult then asks the young person some questions and the young person’s responses are recorded in each house. For example, the adult could ask questions about what

is going well at school. After the young person has given their responses, the adult would add these to the relevant house, in this case, the house of good things. This would be repeated until all three houses are filled.

Option 2: The adult shows a young person a picture of three houses and then asks the young person to draw their own version on a separate piece of paper. The adult would then explain the name of each house: house of good things; house of less good things; and house of dreams. Next, the young person would be asked to write or draw pictures of all the ‘good things’ about something, for example, school. As the young person draws or writes, the adult can ask the young person for more information about what they have drawn or written. This process would be repeated with all three houses.

Example

The below three houses are from Gesher’s conversation with students for the Changing Schools, Changing Lives article.

Looking at what ʻhappinessʼ means to Gesher, it is defined as the need for children to feel broadly secure, to feel satisfied about whatʼs going on with them and to experience a sense of safety in their wider environment In this article we speak to Laurel Freedman, an Educational Psychologist and chair of the Mental Health, Wellbeing and Happiness committee at Gesher, and unpick the schoolʼs Mental Health, Happiness and Wellbeing work, to explore why faring well really matters for children and how you prioritise it in a school.

At Gesher the mental health, wellbeing and happiness (MHWH) of children and adults are core to our ethos. This is grounded in, and driven by, an understanding of what is most important to children and young people.

Children often come to the school having not had their sensory and emotional needs met in mainstream settings, leading to ʻoverwhelmʼ. Overwhelm, and the anxiety that comes with it, blocks children from flourishing and reaching their full potential.

Alternatively, security, safety and solid attachments create the foundations for children to take risks. Learning is all about taking risks; managed risk is at the core of all exploration and education. In short, happy children learn.

“In short, happy children learn.”

This isnʼt only true for children. Staff and parents also need to feel safe, secure and listened to, in order to create the same environment for children. When concentrating on mental health, happiness and wellbeing, Gesher also wanted to create the space and mechanisms for adults to voice their opinions, hear praise and talk about what they needed for their own wellbeing.

The schoolʼs MHWH policy was developed as a means to articulate and pin down the practices they had been developing and refining, in order to keep a record of what they had been doing and to share that with others. The following five steps are drawn from this policy & accompanying work.

1. Learn from others

Look elsewhere for inspiration and to gather ideas.

For example, Gesher gathered ideas from:

“Itʼs important to note that Gesher is still in learning mode, and probably always will be.”

2. Establish governance for the work

Gesher established a Wellbeing Committee, comprising the CEO, School Wellbeing Lead & Music Therapist, and School Educational Psychologists, focussed on:

(A school wanting to establish its own committee might also want to include pastoral care and safeguarding leads.)

3. Build the right team, skills and approaches

On top of the committee, the school also appointed multidisciplinary specialist workers to meet specialist needs that some children might have. These included:

However, Gesherʼs MHWH approach is ʻwhole schoolʼ, meaning itʼs owned by everyone. The work is designed to feel connected and to promote the fact that everyone has skills and a role to play in promoting it.

Whilst some staff are appointed for their specific expertise, every member of staff is trained and supported to spot early warning signs and the different needs of each child. There are also displays, celebration assemblies and constant discussion opportunities in the school to talk about it.

4. Create tailored support strategies for each child, promoted by your curriculum

Each child has a tailored support strategy, focusing on hearing each young personʼs needs and voice.

This strategy closely involves families, building important links between home and school. These strategies, and the emotional scaffolding tools used within the curriculum encourage:

Activities that promote this include:

5. Think about your impact & how you assess wellbeing

Observe changes in the resilience of children (and adults) who face adversity and struggle. The coronavirus pandemic, for example, helped the school to see this in action. Gesher was able to stay open during lockdown, knowing that stability was needed for children. But staying open wasnʼt the only thing that created that safety. The children were still able to thrive and learn during such a difficult time because of the consistent and tailored support strategies put around them. supported and listened to? Do they feel like owners of the work?

Talk to parents. Parents have told us that they have a ʻdifferent childʼ, they describe the changes to their childrenʼs interests, interactions, appetite for learning and in the way they look forward to things. All teachers will observe this themselves, but itʼs really validating to hear parents observe it too.

Ask your staff for feedback regularly. Do they feel supported and listened to? Do they feel like owners of the work?

The above steps are drawn from one schoolʼs learning journey to date. Itʼs important to note that it is still in learning mode (and probably always will be). Their next focus is an exploration of adolescent transitions and good mental health.

Professional Prompt Questions

- Whatʼs needed to guarantee children feel secure and valued in school?

- How can schools ensure that children are really well known, and that they know that they are known?

- How do you build security and support for staff in SEND schools?

- How can you make mental health, wellbeing and happiness everyoneʼs business in school?

Laurel trained as a primary school teacher over 40 years ago and has had a number of roles and professions both in England and Israel, including teaching adults and pre-school children, and childminding. After qualifying as an Educational Psychologist (EP) in 1996, she worked for the London Borough of Enfield for seven years and then moved to Norwood (Binoh) where she managed the EP team, working predominantly within the Jewish community. During this time, she also spent five years on a secondment to the Tavistock Centre, working as a part-time course tutor on the Doctorate for Child, Community and Educational Psychology. Since leaving Norwood in 2013, Laurel has worked as an independent EP and is now semi-retired.