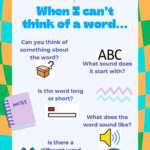

A word-finding difficulty is when a person knows and understands a particular word, but has difficulty retrieving it from their brain to use in their speech. This is similar to how we sometimes feel something is on the ‘tip of our tongue’. Children might not able able to find the word at all, they might retrieve a word that sounds similar to the one they want or they might produce a nonsense word. Check out this website to learn more about the signs that indicate a word-finding difficulty and how you can help support at home. The linked document below also contains prompts which we use at school to help support retrieval of the word they are looking for.

There are two ways in which we may learn language: ‘Analytical’ processing and ‘Gestalt’ processing. Typically we think of language development as learning single words and building them up to full sentences – this is called analytical processing of language. Gestalt Language Processors on the other hand, will start by using whole ‘learned’ phrases, progress toward using single words, and then build their back up to more functional and ‘spontaneous’ phrases. Understanding which way our children are learning language will not only help us to understand them more effectively, but also help us to further support their development of functional communication.

Below you can find a video which explains more plus a link to one of our PDFs on the topic and a website which contains some top tips for parents.

This clip is drawn from Dan Siegel’s hand model of the brain. It is a metaphor to help explain what might be happening in our brains when distressed. It depicts an ‘emotional’ and ‘thinking’ brain but this does not mean they are separate parts of the brain. The ‘emotional’ and ‘thinking’ brain are descriptive metaphors of brain functioning to explain how our brains may be in a more ‘reactive’ rather than ‘reflective’ mode. The hand model clip is used in Emotion Coaching training to show how Emotion Coaching can help to guide the brain to develop a more reflective mode (thinking brain) rather than remain in a reactive mode (emotional brain).

What is self-regulation and why is it important?

It is tempting to label challenging behaviour as oppositional, defiant, manipulative, and attention-seeking. But, challenging behaviour is often not in children’s control. It is more accurate and helpful to understand this behaviour as a sign that children cannot handle their big emotions (e.g., mad, sad, sacred). When they feel overwhelmed, their emotions are getting the best of them. That is, they cannot self-regulate. You can read more, here.

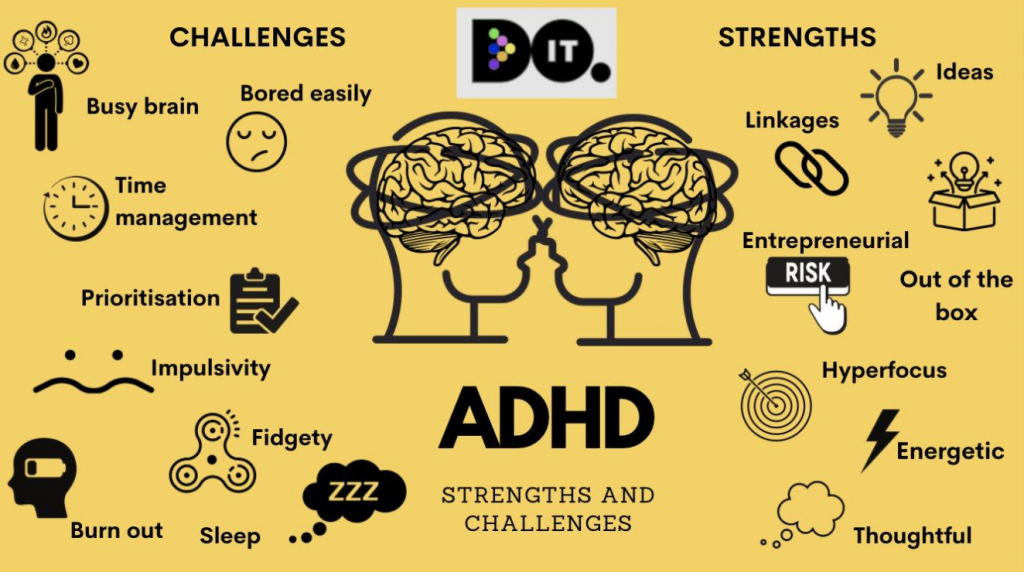

Myths and Stereotypes about ADHD

There are many myths and stereotypes when it comes to ADHD. Even the name is misleading. People tend to think of ADHD as having a lack of attention but in fact they do not have a deficiency in attention, but an abundance of it! The difficulty is in not being able to control this attention. (https://mashable.com/article/what-is-adhd-myths-stigma)

It is important to acknowledge and fully understand the difficulties faced so that the necessary supports and accommodations can be in place but we must also recognise the strengths that having a neurodivergent brain offers.

Here is one ADHDer’s personal story of success – Jessica Mccabe has her own YouTube ADHD channel. Click on the link to hear her story.

Failing at normal – one person’s success story

ADHD and Autism

Research suggests that 50-70% of autistic people are also ADHD. There are characteristics that overlap but also that often contradict each other.

Websites

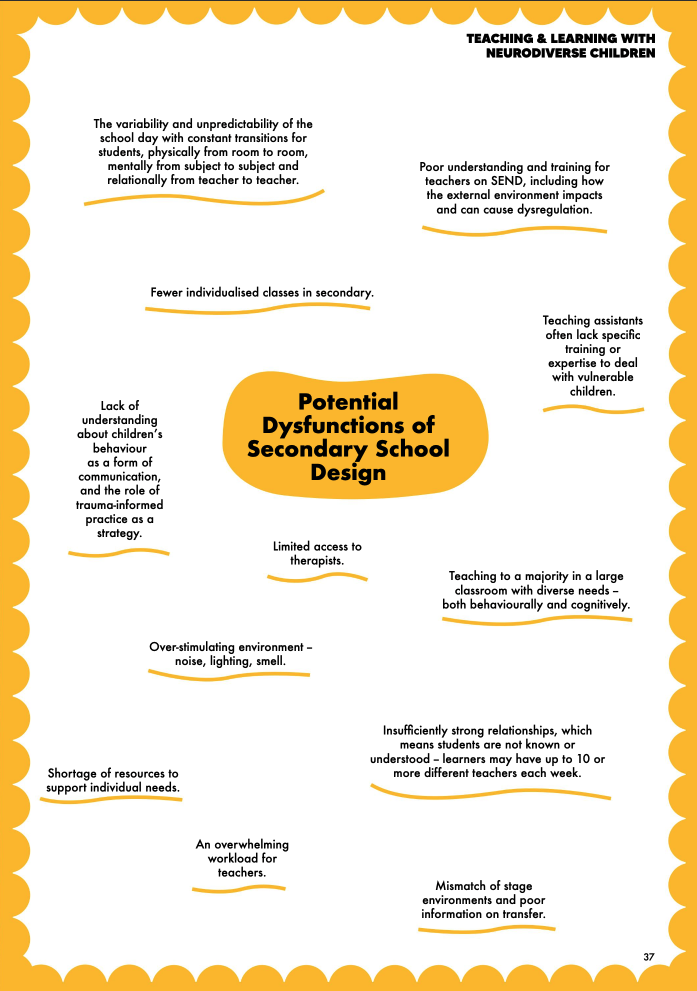

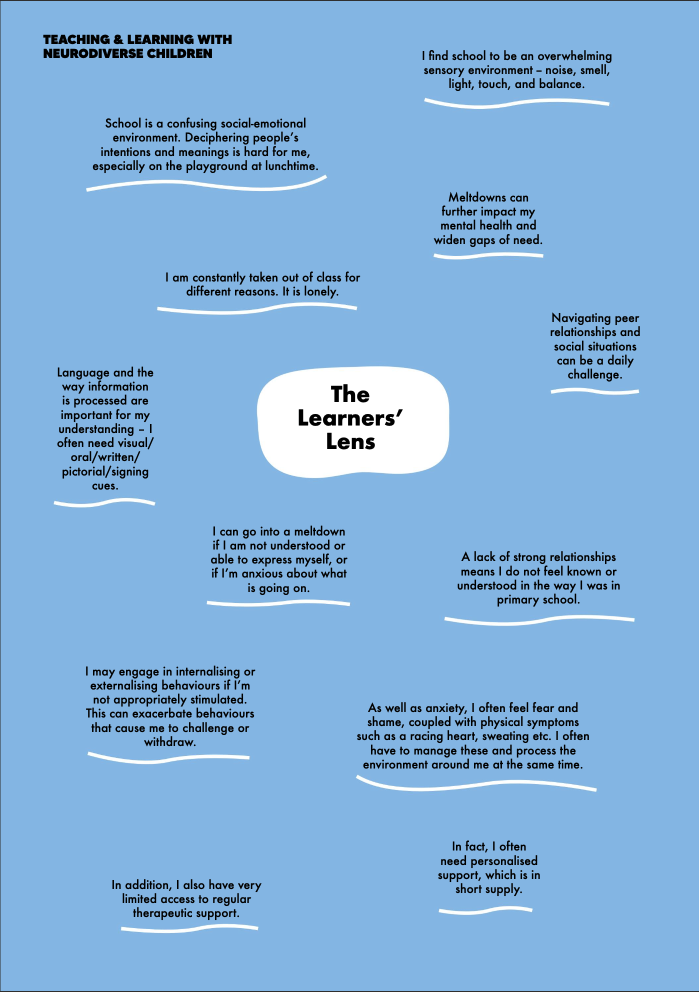

Why is School a Tough Place for Neurodiverse Children?

Ali Durban

A Short Reflection on Bravery

If all schools were judged by the provision they make for their most vulnerable learners (which feels not to be an unreasonable measure) it could be that there would be more “inadequate” judgements than there are currently. For some learners attendance at school requires reserves of courage.

Bravery is not a word that we would want to define any child or young person’s daily experience of school. After all, school is meant to be a place of safety, fulfilment, and positive relationships, yet for thousands of differently abled children and young people, navigating their normal school day is challenging, complex, damaging even, and bravery is a daily necessity of survival. In his recent book ‘The Inclusion Illusion’, Dr Rob Webster highlights the everyday experience of students with SEND in mainstream school as being characterised by separation and segregation.

School is meant to be a place of safety, fulfilment, and positive relationships, yet for thousands of differently abled children and young people, navigating their normal school day is challenging, complex, damaging even.

‘There are structures and processes ingrained within these settings that serve to exclude and marginalise them (children and young people). The arrangements that led to this might be defendable if they were necessary for creating an effective pedagogical experience. Yet the evidence… suggests that, if anything, they result in a less effective pedagogical experience.’

The Policy Context

Over 1.4 million children in Britain are reported to have some sort of special educational need and we all know that the unassessed number is probably much larger. Three-quarters of these (about 1.1 million) are on SEND support and 365,000 have an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP). The current SEND Green Paper talks about ‘a clear vision for a more inclusive system’ but gives no real sense of how it will be achieved. To put this inclusive thinking into context, following a consultation on behaviour management policies and exclusion, the Department for Education appointed a “behaviour tsar” to create “behaviour hubs”. Guidance also referred to the use of “removal rooms” in schools as a punishment and to the use of managed moves as an early intervention measure for pupils at risk of exclusion. To be clear, the children and young people most impacted by these measures are the most vulnerable in society. Mostly they are those with SEND.

The Government (and constant merry-go-round of Education Ministers) continues to wrestle with inclusion and SEND system reform, with no clear approach to system transformation in sight. For this article, we set aside the complexities of system change and instead take a grassroots-level deep dive into exactly why life in mainstream education is so tough for differently abled students.

Introduction

Gesher’s Ashleigh Wolinsky, Speech and Language Therapist, and Ingrid Mitchell, Educational Psychologist, have extensive experience working with SEND learners. We asked them to share some insights drawn from that professional experience. It will not be a shock to readers to learn that SEND identification, poor resources, and assessment and diagnosis delays are some of the consistent features.

However, with that as background we have extracted from the interviews three further clusters of issues:

- Those that are endemic to ‘school’ — the way secondary school in particular works.

- Issues that are unique to the learner — the needs of a ‘differently able’ youngster.

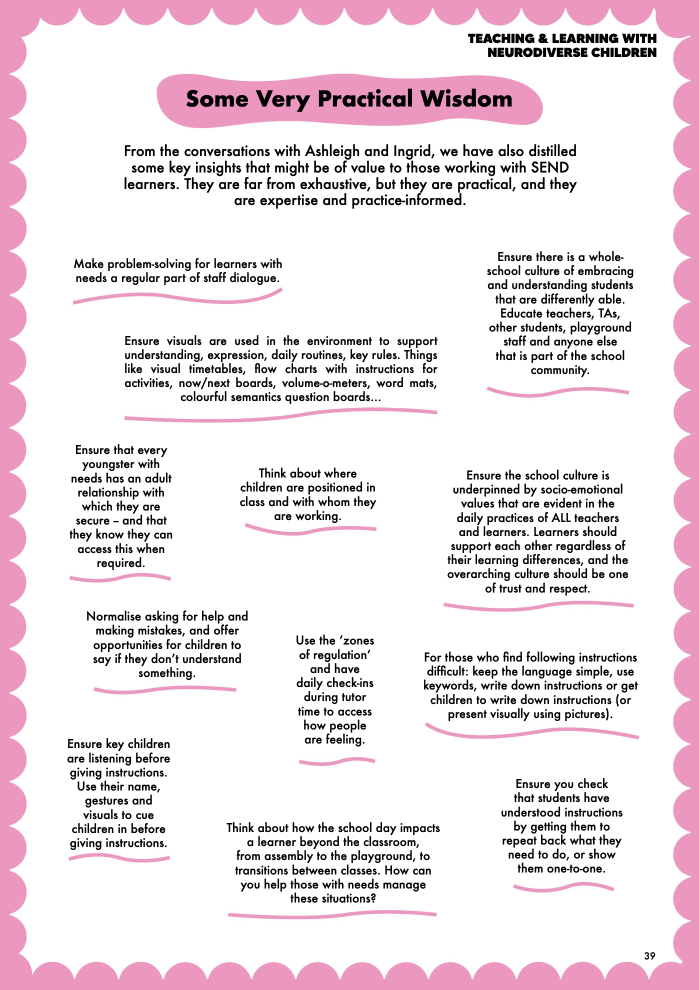

- What we have called ‘wisdoms’ — some practical suggestions that may be of help.

End Note: This article is not a criticism of mainstream schools, nor of secondary schools in particular. Nor is it a eulogy for special school provision. Let’s be clear: we believe that both mainstream schools and special schools can do a great job for neurodiverse SEND youngsters — hence the insights and advice.

What we are also clear about, though, is that hundreds of young people across the country have a potentially damaging and unhappy experience of school and that there is knowledge about how things could be better. This piece is a small contribution to that, drawn from those with expertise.

Professional Prompt Questions

What most challenges your school’s SEND practices in this article?

Are there things in the ‘practical wisdoms’ section that your school might like to adopt?

Might it be of value to your school to create a Learners’ Lens of insights from your neurodiverse children?

The current education system in the UK is setting up many autistic young people to fail. This is especially true of the assessment practices where the current system relies heavily on out-dated and old-fashioned standardised exams and tests which are unable to capture a young person’s real strengths and abilities.

Joshua is an autistic young person who did not attend Gesher but spoke at our most recent Critical Friendship Group meeting, sharing his lived experience of the assessment process and his insights into how it could be improved for neurodiverse young people.

Here, Joshua, now aged 18, tells his story of mainstream education and offers his advice to schools.

The importance of school support

In my early years I struggled to make friends. Some of my earliest friends were basically asked by my teachers because they felt bad for me.

I was diagnosed in the summer of 2012 between Years Three and Four though I wasn’t told until later that year because my parents were working with my school to find the right way to explain it to me and my peers.

During primary school, my needs were well provided for. When I got my diagnosis, the school helped my parents put together a small Powerpoint that was used to explain it to me. This was then lightly adapted and shown to my classmates so they too could understand better.

I could leave lessons to take a breather and a walk if I needed to, as I struggled to sit still and focus for extended periods, I had a dedicated space I could go to cool off if I had gotten into an argument or fight over something, which was common because I was easy to anger as a child. Any time I felt I had a problem, I knew where I could turn.

The school helped me nurture the talent I had, often letting me complete tasks in a different way to the usual methods if it meant I was able to do it “my way” which would often involve a very flashy Powerpoint presentation.

When schools focus on results, not the pupil

When I got to secondary school, however, there came a change. The school very much ignored any kind of ability outside of traditional educational achievement: you either fit their mould for a good student or you didn’t. And if you didn’t, you were left in the dust.

At secondary school, support I had grown dependent on during primary was almost non-existent and the staff were not friendly towards students. Even the SEN staff seemed to be less than interested.

I will never forget the time I went to our KS4 mental health advisor and told her about how bad my depression had gotten at the time, to which she laughed and told me that I seemed to be very good at telling jokes. A story I genuinely wish I was making up.

When it came to work, methods I had grown so accustomed to were shut off to me because the school only wanted results in one specific way. You did it their way, or you failed entirely.

How the current assessment system sets neurodiverse children up to fail

I moved from secondary school to a different sixth form where support was available and actively advised to be used, and where I could work how I worked best, even if that meant going back to the flashy powerpoints like I would have done aged 10. As I grew up and came to understand what autism is and what it is to be autistic, I found it easier to make friends, especially in cases where they were also autistic.

Despite being in a better school, I spent most of my A-level time suffering extreme mental health issues and it was a miracle I even made it to sit the examinations

And now there’s a big problem. I’m currently looking for apprenticeships in software development, but on my applications, I can only put my grades, not the fact that I have neurodiversity where often the pressures of the school can break a student so easily and so quickly.

Starting out on your career becomes really difficult when, even though you are a strong candidate, the only important thing is your grade which says: “you got this – this is all you are worth”.

How schools can learn from students’ experiences

For schools, honestly, I think my main piece of advice is just to listen to autistic students. A lot of schools, teachers, and just people in general confuse autism with being unable to look after yourself and understand your own needs, when in reality, it’s very much the opposite.

I was very lucky as my primary school helped me every step of the way to understand myself and be as comfortable talking about it as I am now.

The person who knows best what the autistic person needs, will ultimately be the autistic person.