Practical Personalisation

Loni Bergqvist

Loni was a teacher at High Tech High before coming to the UK to support the REAL-Projects programme in 2014. Since then, as founder and partner of Imagine If, Loni has worked with schools around the world to re-imagine education. Her project-based learning expertise has been used in several international initiatives and yet she finds time to be a source of friendship and expertise to Gesher.

Differentiation is Not Personalisation…

Ditch the word differentiation. Never use it again. Forget it exists.

By default, using the term differentiation causes us to look first at and make assumptions about what’s different about students before designing assessment or a lesson. We weigh these differences against what’s seen as ‘normal’ and by doing so, we categorise without really properly getting to understand individual students. Differentiation is a quick and inadequate way to streamline the process of knowing or categorising our students. We assign them labels so that we feel as though we understand their needs… but do we really?

Personalisation, on the other hand, begins with the unwavering belief that all students are capable of excellence. All. But, in order really to live out this philosophy, it takes a commitment to dig deep into children who enter the walls of the classroom. Personalisation starts with deep understanding. It’s not a term that is used exclusively with students who struggle to read or have learning challenges, or who are identified as being gifted. Personalisation should be done for every single student, such that we can give all learners access to their gifts and mitigations for their challenges.

This is not an over-idealisation. In adulthood, people find, navigate and express their gifts – intellectual, practical, emotional, and spiritual. We identify with and gain respect for what we can do or enjoy doing. Schools have tended to emphasise, for many learners, what they can’t do.

Personalisation starts in a different and more optimistic place.

Idea One: Create a community of learners

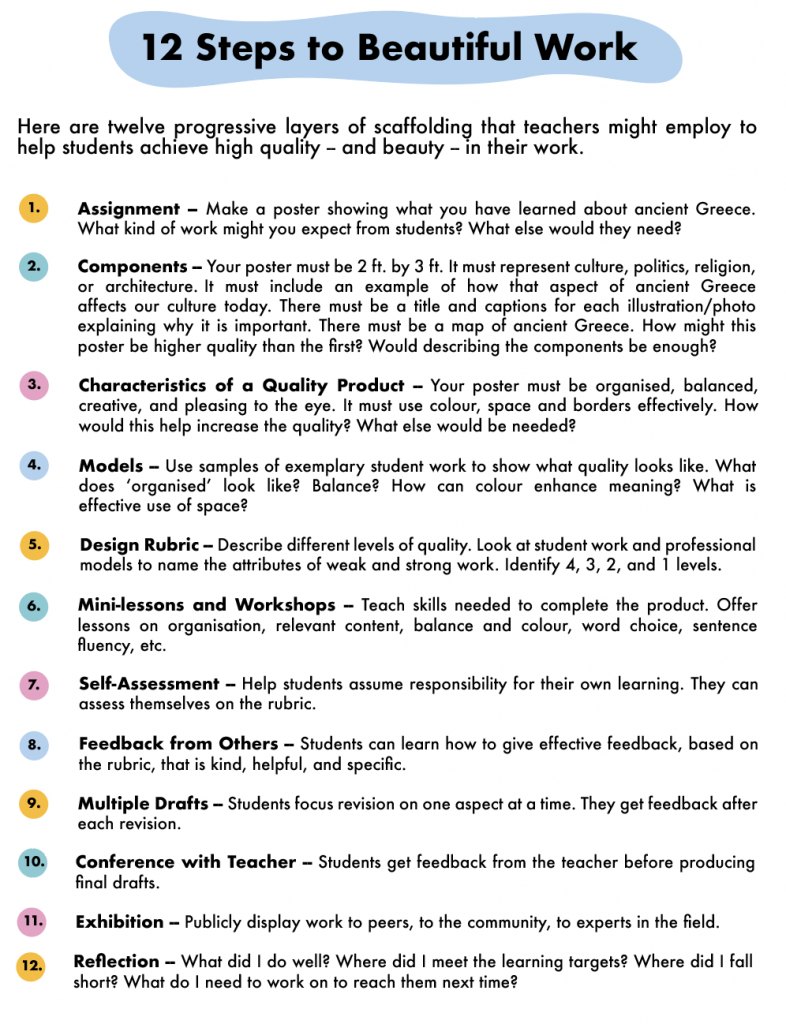

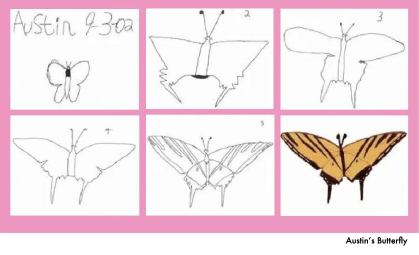

Creating a community where everyone (regardless of perceived academic ability) feels included, valued and comfortable is essential for all students and especially necessary for students who may have been marginalised in the past and felt excluded. At High Tech High, for example, they have a simple mantra: We expect all learners to be successful and to produce beautiful work. It is the responsibility of the entire class to help them do that. THAT is a community of learners.

Things we can do to create these learning communities

Facilitative of Classroom Culture:

- Knowing students individually

- Allowing for student voice

- Teachers openly being learners in the classroom, too

- Mixed groupings – gender, experience, abilities

- Encouragement of risk-taking and celebrating it publicly

- One-on-one conversations with students

- Celebration, recognition, and affirmation activities.

Techniques, Tools, and Activities:

- Critique of work activities using peer feedback

- Appreciations share-out at the end of a class

- Individual reflection – and perhaps journal use

- Use of protocols that scaffold learning and contributions

- Question wall (a Parking Lot for questions and ideas)

- Think-Pair-Share

- Ice breakers and opportunities for students to share with each other (non-academic)

- Show & tell activities that highlight student passions and interests

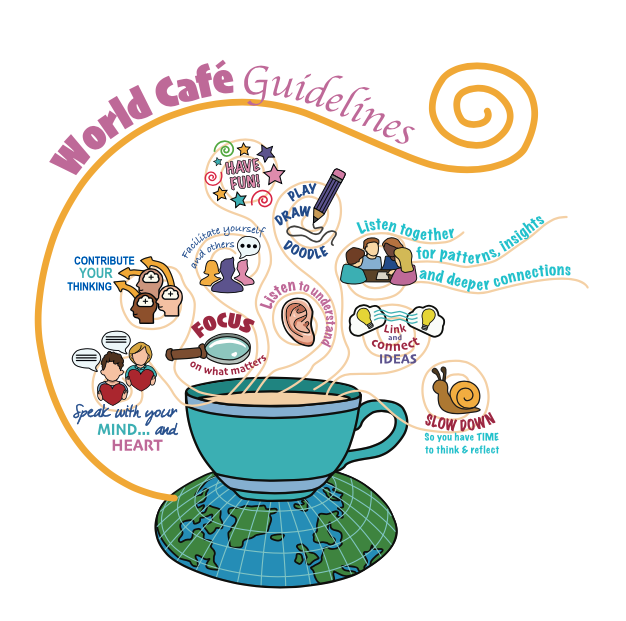

- Variety of activities that necessitate different talents (Socratic Seminar, World Cafe)

- Display of ALL beautiful work where students have invested, regardless of whether it’s ‘the best’.

Idea Two: Focus on what students CAN do, first.

It’s easy to start the year by looking at student deficits. However, any student who has struggled with school in the past, knows whether they’re perceived as being ‘good’ or ‘not good’ at school. The most important thing is to build confidence in students by examining and recognising what students can do, and what they’re already good at, to provide more access points to help with areas that need development.

Ways we can focus on what students can do:

- Teacher/student interviews

- Be flexible in the ways students show understanding (dictation, partner writing, pictures, etc.)

- Take a ‘learning preferences’ survey and design lessons or learning pathways around different types of learners

- Activate prior knowledge and related knowledge before new knowledge

- Ask them: ‘What are you comfortable with? What do you struggle with?’ They know

- Invite other students to celebrate what they value about peers

- Some of the strategies in Idea One.

Personalisation begins with the unwavering belief that all students are capable of excellence.

Idea Three: Provide scaffolds for students to reach higher. Don’t lower expectations.

When creating scaffolds for students to complete a desired task, it is essential the support matches with the need of an individual student. Determine what the task is, what an individual student may need in terms of support to reach the desired task and provide resources accordingly. We do this instinctively when a student has a visible, physical barrier – a broken leg; a sight impairment – but we are less intuitive about more generic or subtle support strategies.

Ways we can scaffold learning:

- Graphic organisers (give the option to all students, some will need them without ever officially getting support)

- Modify assignments to do less if it’s the same skill

- Allow dictation to a teacher or another student

- Partner work

- ‘Workshop Groups’ with a particular task as a theme. (Open these to all students who may need support! They can also be done after school.)

- Chalk Talk (Protocol available here)

- Think-Pair-Share (Resources available here)

- Include visuals with text

- Untimed Learning Stations, so that students can go at their own pace in a supported context. You can combine this with Daily Checklists.

Idea Four: Honour student interests

This one is really important. Those old enough to remember Barry Hines’s novel (and film) “Kes” will remember the young boy who received no affirmation in school, but who kept, trained and flew a kestrel outside school. When an empathetic teacher joined him in the fields near his house to watch, he was awestruck.

Our students have rich lives outside our classrooms – they fish, they look after siblings, they go to evening classes, they have collecting hobbies, they are masters at online games, they play the guitar… And the more we can do to bring these experiences into school, the better chance we have of honouring who our students are, what they are passionate about and what they are skilled and knowledgeable about.

Ways we can involve the interests of students:

- Choice in assignments (what to write about, the theme of a project, etc.)

- RAFT (Role, Audience, Format, Topic) Resources here: https://www.edutoolbox.org/rasp/840.

- Conduct home visits and meet with students and their families

- Have Show and Tell each Friday with different students presenting each time

- Give open-ended projects where students can include their own ideas for products and exhibitions.

End Note: Personalisation, then, is basically about designing learning tasks and environments and classroom culture which optimise every student’s chances of success. It is both as simple and as difficult as that. And if the range of suggested ideas above seems daunting, remember two things:

- Just as we need to know our learners well to optimise their learning, so we have to know ourselves — and what we feel confident about and where we need help.

- Teaching is not an individual sport – or at least it shouldn’t be. Teaching with other teachers and/or with support assistants can create a context for dialogue. So, too, can the design and planning process, in which peer critique is as valuable for teachers as it is for students.

Within each of these themes, there are eleven badges for the students to work towards achieving. In the ‘My Home’ theme, for example, the badges range from ‘Clearing the Table’ to ‘Preparing for Social Occasions’. ‘While each badge is very different they are all designed to focus on developing creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving, decision-making, the ability to communicate and collaborate, as well as commitment to personal and social responsibility.’

Within each of these themes, there are eleven badges for the students to work towards achieving. In the ‘My Home’ theme, for example, the badges range from ‘Clearing the Table’ to ‘Preparing for Social Occasions’. ‘While each badge is very different they are all designed to focus on developing creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving, decision-making, the ability to communicate and collaborate, as well as commitment to personal and social responsibility.’