What All Schools Can Do to Support Neurodiverse Learners

With thanks to Pete Wharmby (Centre for Research in Autism and Education, CRAE Annual Lecture, 2023)

10 Things All Schools Can Do

- Make sure that all staff know the profile for all relevant learners.

- Have a mentor for each neurodiverse learner – one in which they have some agency.

- Educate all staff about autism – if they have knowledge, they can do a lot.

- Work with your community – employers need to understand neurodiversity, too.

- Open up the issue of difference – move it from insult to fascinating.

- Promote tolerance of and accommodation of difference.

- Accommodate idiosyncrasies (e.g. stimming, walking around, repetitive behaviours, sensitivity to noise, obsessive interests).

- Make the school sensitive to known or potential triggers “of stress or behaviours”. e.g.

- Changes to routine or schedule

- Group work

- Work deadlines

- Presentations

- Reading aloud

- Picking teams

- Prioritise positive relationships with learners and parents (e.g. regular dialogue with parents; support groups for parents) – working together is in everyone’s interests.

- Have available appropriate therapeutic strategies.

Guidance for Schools

The 10 suggestions above provide a useful checklist. They can also be used to create a workshop activity for staff that will sensitise everyone to the issue of supporting neurodiverse learners. They were stimulated by Pete Wharmby’s presentation at the 2023 CRAE Annual Lecture, and most of them were specifically referenced there. Pete is an autistic teacher, writer, speaker, advocate and author. Below are two suggestions about how “10 Things” might be used.

- The first is a simple “bright spots” activity, designed to identify the best of what is currently happening in all 10 areas. The logic of discussing bright spots is to build from the best of what currently happens. “What are the characteristics of this that could be applied more broadly?” and “What would be required to have more like this?”

- The second is an evaluative activity to identify strengths and areas for growth – what is going well (or not) and what more might be done.

Activity 1

- Pre-arrange groups so that there is a good mix of experiences and roles in each group. Prepare a facilitator for each group – someone who will advocate for the activity.

- In groups, discuss the “bright spots” in your school for each of the 10 items. What is the best of what you do? What are the key features of these bright spots?

- Then, come together with new ideas being suggested for each of the 10 items, where relevant, based on the principles or features of your bright spots.

Activity 2

- Before the activity, create sets of cards with one of the 10 suggestions on each card plus five blank cards (to add new things). One set is required for each group.

- Pre-arrange groups (as above).

- First, each group discusses whether they have additional ideas to add on the blank cards.

- They then sort out their top 10 as a group.

- Groups come together and are facilitated to create a composite or consensus top 10 across the groups (“Our school’s top 10 ideas”).

Subsidiary activity either in groups or as a whole staff:

- Arrange this top 10 into three groups – things we do well; things we need to improve on quite a lot; things we value but are not currently ready to do.

- Using post-it notes (green for positive affirmation, amber for creative improvement ideas, red for “we’re not close on this”), decorate ideas around the ten cards, starting with amber, then green, then, if time, red.

Farmington Public Schools

Our fifth graders took action in collaboration with the Farmington green Efforts Commission by participating in a local anti-idiling campaign. As civic-minded contributors, this was a wonderful opportunity to engage in stewardship in our town. Students have been studying how human activities impact the Earth’s sphere, and more specifically, how the burning of fossil fuels impacts the atmosphere.

As part of this project, fifth graders collected and analysed data about idiling in the west woods parking lot before and after school. They learned more about idiling from Ms. Caitlin Stern, an enivronment analyst in the Bureau of Air Management at the Department of Energy and Environmental protection.

Next, in a special appearance on the Wildcat News, Ms. Cate Grady-Benson of the Farmington Green Efforts Commission explained the charge of their committee and its campaign. She invited students to participate in a sign-making contest to promote anti-idling in our town.

In order to learn what makes an effective sign, students used several resources, including a presentation from the West Woods art teacher, Mrs. Lantange. She offered tips and suggestions on how to think like an artist while creating designs (colours that work well together, the right medium, and excellent craftsmanship).

Eight of the signs designed by students were selected by the Green Efforts Commission. Final image edits were done by a Farmington High School students under the guidance of the art teacher. The signs will be professionally printed by DEEP and posted at each of the Farmington schools and the Town Hall.

Learning Targets

As a civic-minded contributor, I can take action to protect the Earth’s atmosphere. I can promote community awareness about idling by collaborating with the Farmington Green Efforts Commission & DEEP.

Students’ Reflections

“I think it’s good to take action because there’s things in the world that we need to stand up for. Before this unit I didn’t know about idling. I’m pretty sure even my parents didn’t, but I told my parents and they haven’t been idling ever since.”

– Jahnvi

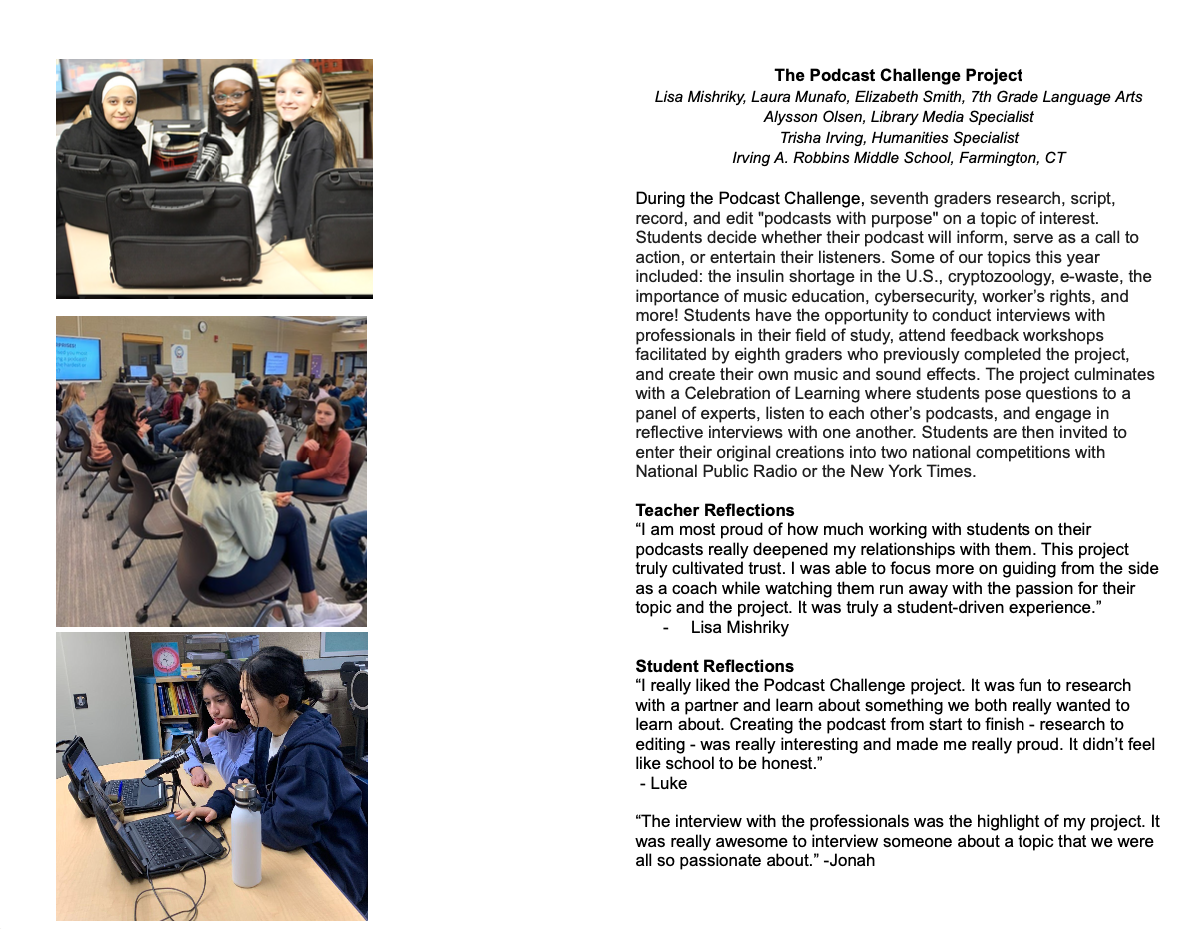

Lisa Mishriky, Laura Munafo, Elizabeth Smith, 7th Grade Language Arts

Alysson Olsen, Library Media Specialist

Trisha Irving, Humanities Specialist

Irving A. Robbins Middle School, Farmington, CT

During the Podcast Challenge, seventh graders research, script, record, and edit “podcasts with purpose” on a topic of interest. Students decide whether their podcast will inform, serve as a call to action, or entertain their listeners. Some of our topics this year included: the insulin shortage in the U.S., cryptozoology, e-waste, the importance of music education, cybersecurity, worker’s rights, and more! Students have the opportunity to conduct interviews with professionals in their field of study, attend feedback workshops facilitated by eighth graders who previously completed the project, and create their own music and sound effects. The project culminates with a Celebration of Learning where students pose questions to a panel of experts, listen to each other’s podcasts, and engage in reflective interviews with one another. Students are then invited to enter their original creations into two national competitions with National Public Radio or the New York Times.

Teacher’s Reflections

“I am most proud of how much working with students on their podcasts really deepened my relationships with them. This project truly cultivated trust. I was able to focus more on guiding from the side as a coach while watching them run away with the passion for their topic and the project. It was truly a student-driven experience.”

– Lisa Mishriky

Students’ Reflections

“I really liked the Podcast Challenge project. It was fun to research with a partner and learn about something we both really wanted to learn about. Creating the podcast from start to finish – research to editing – was really interesting and made me really proud. It didn’t feel like school to be honest.”

– Luke

“The interview with the professionals was the highlight of my project. It was really awesome to interview someone about a topic that we were all so passionate about.”

– Jonah

Creating a Life Skills Space Within a School

Danielle Petar, Emily Bacon, Michal Geller

At Gesher we want our young people to enjoy school. We want them to enjoy learning with one another and supporting each other to succeed. We want them to have great experiences; to love physical and creative activities; to enjoy the unity of a shared faith; to find things in the curriculum that they can be passionate about; to be proud of their exhibitions of work and the real-world projects that make a difference in our community. And, of course, we want them to leave us with the best qualifications possible.

All that having been said, we are a school for young people, many of whom started their school career in a mainstream school which was not well equipped to support them. Parents (and young people as they mature) inevitably have concerns about how well they will cope with the mainstream life of employment and relationships and independent living. This is the world beyond Gesher.

And this is why we have developed a coherent, progressive and continuously evolving life skills curriculum. We are passionate about preparing learners to be assured and adept when they eventually progress from Gesher, as employees, friends, partners and citizens of the world.

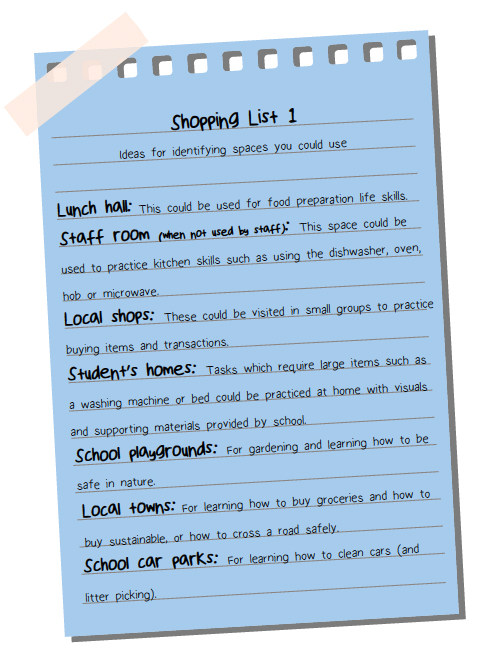

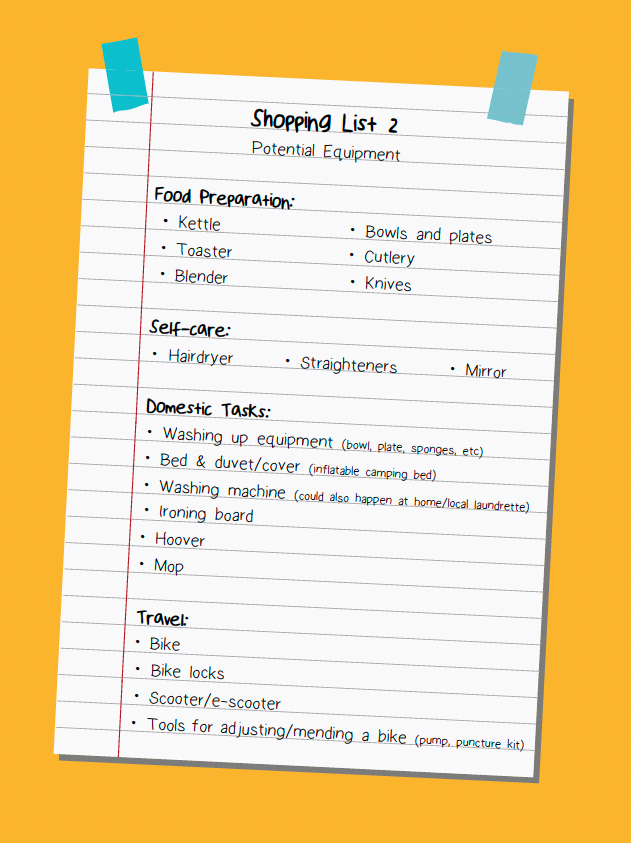

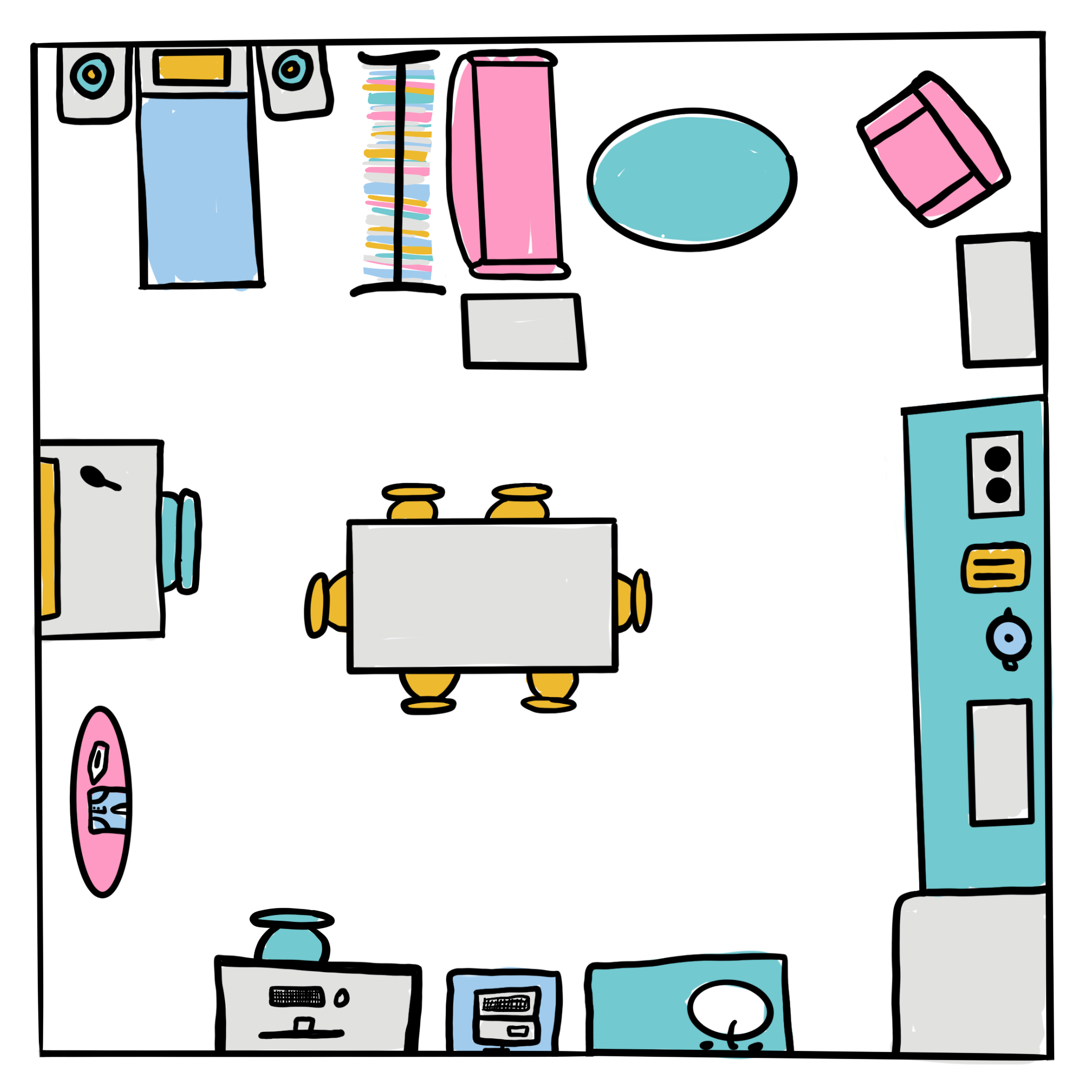

The Gesher Life Skills Space — from top left (clockwise): bed, wardrobe, lounge area, fully functioning kitchen with hot plates, toaster, kettle, microwave, blender, fridge, sink, dining table and chairs, cash register, desk and computer, ironing board and iron, and a ‘my body’ area with a mirror and personal grooming tools.

Creating a life skills space within a school

Ask ChatGPT what you need to set up a life skills classroom and you’ll be given a list of eight steps which include finding a space, making a budget and employing a member of staff. Do some of your own research via academic articles and practical textbooks and the same three themes emerge. Sadly, what the AI and the “old-fashioned” research tool don’t take into account is that schools are not generally known for having spare rooms, giant financial budgets, or bonus staff on hand to deliver extra lessons. It can therefore be difficult to know where to start with something like life skills, which generally falls largely outside the traditional curriculum subjects like Maths, English and Science.

In Issue Two of The Bridge, we featured an article about Gesher’s life skills curriculum, so we won’t pretend that we were starting from scratch when we created our life skills classroom space. We knew what our curriculum required by way of facilities. We also won’t pretend that we weren’t lucky enough to have a small space in our school, a modest budget and a skilled member of staff to deliver our sessions. Perhaps we made our own luck!

However, the journey we have travelled puts us in a position to share some of our insights in a practical and accessible way. We are also conscious that, as a result of our own journey, there isn’t a huge amount of practical advice out there for schools wanting to implement and integrate life skills-related learning. We hope this article helps.

Ideally you will find a space, but it can be a shared space.

How we’ve done it

We moved school sites in 2021 and, as such, were in the fortunate position of being able to include in our plans a dedicated space within our building for life skills – in other words, to give it equal claim in the allocation of space, rather than stealing space back from existing use. However, even the room we are currently using is a temporary solution which is shared with our library. (Although, of course, library use is a life skill, too!) To manage this space the room is carefully timetabled to allow for classes to use the library and for classes to use the life skills space. The room is also used for lunchtime clubs and school council meetings, and can be available as an extra learning space.

Things you could try in your setting

Despite the title of this article specifically referring to a space, there is no necessity for life skills to take place in just one place. We could have called it “Creating a life skills mindset”. Areas such as the lunch hall and the staff room (when not being used by staff) are ready-made life skills areas because of the practical and real-world activities that take place in them. The lunch hall, for example, can be used to practise setting the table and preparing food while the staff room is likely to contain a dishwasher, sink, and perhaps even an oven, making it an ideal environment for students to work on kitchen-based skills.

What’s coming next

One of the end goals for the life skills space at Gesher is to have a full-size, self-contained flat which includes a kitchen, bedroom and living area for students to be able to access during their life skills sessions. To do this we are keen to have students’ input to the design and to make it relevant to their interests.

Making good use of the space

How we’ve done it

Our classroom space is set up to emulate elements of a small flat with a kitchen area, a bed and a sofa. Within the room, each item is labelled to support the learning of organisation skills as well as encouraging independence. All of our students use the room once a week for their timetabled life skills lesson. In addition, we have a group of learners (known as our Life Skills Legends) who attend daily life skills sessions in the space. This gives them more time to practise skills and the way the room is laid out also means that skills can be practised in sequence. For example, when doing bedroom-related life skills, students can take the sheets off the bed, wash them in the washing machine, dry them on an airer and then put them back onto the bed.

Things you could try in your setting

If you don’t have the luxury of having a classroom space where life skills teaching can take place, then an alternative could be to have smaller life skills-related materials stored in one place and accessible to staff. For example, items such as a kettle, a toaster and a blender could be stored relatively easily and used for food preparation skills, while items like hairdryers, straighteners and mirrors could be available for students to practise self-care skills. (We’ve included a full list of resources in the Resources for Schools section of this issue). These materials could then be used for in-school sessions. Activities which require large resources, such as a bed or washing machine, could be completed as part of homework tasks which are developed alongside parents. (It is a feature of our programme that parents are partners – deliverers and accreditors.)

What’s coming next

The next phase would be transferring some of the basic life skills activities into employment-related ones. For example, opening an on-site cafe run by the students would allow for greater independence around their food and drink preparation skills. Other examples are creating an allotment on the grounds, planning and running a school visit, or hosting an employers’ event.

Equipping the space

How we’ve done it

To furnish and equip the life skills rooms, we appealed for donations of furniture from our students’ families and friends, as well as a small amount of financial support from a community donor. Before adding anything to the room we involved parents as well as students to hear their thoughts about what should be included. The clearest piece of feedback that we received from both groups was that the room should be a place where students (as much as possible) could do things independently.

Things you could try in your setting

In the Resources for Schools section at the back of this issue, we have included a shopping list of items that might be useful for life skills sessions. Alongside each item on the list are ideas and suggestions for use. By no means do we have all the answers to these questions, so we would love to hear from you with further creative ideas. You can email us directly via [email protected].

Things that we would like to do…

Moving forward, we would like to incorporate more technology into our life skills sessions. In the first instance, this could involve using online banking and doing an online food shop. However, we would also like eventually to include working with artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT which, despite offering a rather generic answer to our opening question, will undoubtedly be a huge part of our students’ lives in the future.

Professional Prompt Questions

Is life skills education on the agenda for your students, especially the ones most likely to be challenged by the transition to life beyond school?

What ideas in this article have most resonance for you? What ideas does your school have that you could share on an email as suggested above?

If life skills is not currently a high priority in your school, who might you need to gather together to read this article (and the one in The Bridge 2) and to discuss possible ways forward?

Reimagining Assessment: Views From an Autistic Young Person

Joshua Gross

Since the 1990s, the way we assess young people has been dominated by a culture of public accountability and competition, leading to the unhealthy belief that the grade is everything. The idea is now so important that many exams, like GCSEs and A-Levels are referred to as “high-stakes” tests because of the way they determine the next stage of someone’s life.

Those who create the high-stakes assessments claim that they are the fairest and most rigorous tool we have to demonstrate student achievement. However, the evidence used to back up these claims is often insubstantive (Richardson, 2022). One of the consequences of these high-stakes assessments is that young people’s outcomes are reduced to a number or letter which only reflects a very small proportion of their experiences and achievements at school and usually only in academic subjects.

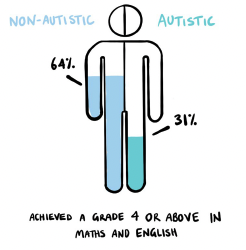

Whilst this affects all young people, data has shown that, on average, autistic young people do not achieve the same levels of academic success as their non-autistic peers assessed in this way. The most up-to-date government data shows that 64% of non-autistic students achieved a Grade 4 or above in Maths and English, compared to 31% of autistic students – and this data is not a one-off. The same pattern exists in the previous three years’ data. While the statistics alone are striking, even more profound are the hidden stories behind the data. As such, in this piece, we share the reflections and experiences of Joshua, an autistic young person who has the lived experience of feeling let down and misrepresented by the current system and who has vital ideas on how it might be reimagined to prevent the same thing happening to others.

“The big problem with existing assessments is that they are the be all and end all when you leave school.” Joshua

The same idea is expressed in the opening sentence to this article and yet what this means for young people can often get lost in the statistics. For Joshua, who at the time of writing is applying for apprenticeships, the implications are clear.

“I can only put my grades, not the fact that I spent most of my A-Level time suffering through extreme mental health issues and that it was a miracle I even made it to sit the examinations, not the six times I almost dropped out and came back to them later… It becomes really difficult to come out the other side and still be a strong candidate when the only important thing is what grade you got.”

Joshua’s solution to this problem would be for schools to recognise the skills that young people have through a more flexible approach to curriculum and to assessment. In Joshua’s case, he has a talent and passion for computer programming and, while he was able to take this as an A-Level, he was still assessed within the constraints of that curriculum and the conventions of exams.

“In my A-level computer science class we had people who had never opened the Python Editor before and we had people like me who had made full video games in one day before… I would be running off doing these ultra-complex things at home that would never be recognised because they weren’t even remotely related to the curriculum. Like, I can make a video game using languages that the curriculum doesn’t even know exist. And I’m just sitting there doing these things, but none of them get recognition. I can do all this stuff and it doesn’t matter because it wasn’t what I was told I had to do. I didn’t fit that specific guideline and therefore it’s not good enough.”

By having a curriculum that is less constraining, less of a rule book, there would be more scope for teachers to work with young people in their area(s) of interest and strength, aligned with their passions. While this would have benefits for all learners, there would be particular benefits for some autistic young people who often have a special interest or aptitude. Recent research by King’s College London, for example, has shown that when adults are accepted as having a special interest, and where it is responded to positively, recognised and valued, this can lead to them excelling in the linked curriculum area (Wood, 2021).

As not all neurodiverse young people will have a special interest that can be assessed within school, it is also worth considering other ways in which a more flexible assessment process would be beneficial. Here, Joshua has further important ideas to share.

“Assessment as it is now is not actually really a test of knowledge, but more a test of memory. I found often that those kinds of assessments really did not work for me, but one that I really excelled in were the two B-techs that I took in Business and Digital Media. Instead of having this one assessment that you’re building up to and studying in unhealthy ways for, you’re working on it throughout the entire course. It’s not one giant thing, it’s a bunch of smaller things. Break one big problem down into a bunch of smaller ones, and suddenly it becomes less of a big problem.”

Joshua’s views about coursework are echoed in the academic literature, which has shown the pedagogical benefits of such forms of assessment, as well as the fact that students prefer it to exams (Richardson, 2015). Despite this, under the current assessment system in England, none of the Maths, English or Science GCSEs have a coursework component which counts towards a student’s final grade. As such, the work that a student does across two or three years of study is condensed and assessed through a few hours of exams. This in turn then shapes their future opportunities. Joshua considers this system to be a particular challenge for autistic young people as “Often the pressures of the school system can break a student so easily and so quickly. And it becomes really difficult to come out the other side and still be a strong candidate when the only important thing is what grade you got.”

There are two more things that we know about the lack of fit between the current assessment system and neurodiversity. One was well articulated by Joshua: “If you emphasise ‘standards’ and ‘standardisation’, then by definition this will not work for autistic young people who are, by definition, non-standard.” The other, which is linked, relates to the idea of “spiky profiles”. Autistic learners are less standardised, less conventional – they have great strengths alongside different challenges. An assessment model that emphasises the challenges (e.g. writing essays) and minimises the strengths and passions (e.g. technical capability, creativity) will serve both autistic youngsters and the system badly.

Endnote

Joshua’s views are those of just one student, but the dearth of autistic voices in both the academic and non-academic literature in this field makes this a provocative contribution and one that we hope is built on by further activity in this area.

References

Richardson, J. T. (2015). Coursework versus examinations in end-of-module assessment: a literature review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(3), 439-455.

Richardson, M. (2022). Rebuilding Public Confidence in Educational Assessment. UCL Press.

Wood, R. (2021). Autism, intense interests and support in school: From wasted efforts to shared understandings. Educational Review, 73(1), 34-54.

Professional Prompt Questions

What rings true for you in Joshua’s comments?

You will almost certainly have neurodiverse learners in your school. Might a small piece of research or a focus group with them help to unearth challenges they face to which you could respond?

Three Big Ideas for Assessment for Schools Hoping to Do Better

Julie Temperley

1. Agree together the outcomes you value most for your learners (the knowledge, skills, values and characteristics). Which of these do you currently assess well?

Some things to try:

Run a whole school enquiry to surface what learning teachers, learners, families, and the wider community consider most important to be able to assess or demonstrate. Knowledge is sure to feature, but so too will skills like problem-solving, and characteristics like confidence and kindness.

Explore together how much time is spent in school on assessing learning that is not congruent with the things that you value. Do you have the balance right?

Co-design with staff, students and stakeholders a learning dashboard that teachers and learners can complete together to track and communicate progress in knowledge, skills and characteristics important to everyone in the school and beyond.

2. Expand the range of assessment tools and methods used in school and grow teachers’ confidence and capability in their use.

Some things to try:

Group assessment – instead of awarding individual marks, teachers and learners agree assessment criteria for group work and, on completion, the whole group gets the same mark. This approach is especially useful in project-based learning, but can be applied to any group-work activity, and encourages the development of skills for collaboration, teamwork and shared responsibility.

Routinely include an element of self-assessment – learners use the same criteria as teachers to “mark” their work, then teachers and learners discuss the differences between their assessments and what might sit behind these.

Mastery learning – learners explore success criteria at the beginning of a unit of learning (perhaps using “exemplar work”) and make as many attempts at some or all of the assessments as they need to, in order to identify gaps in their knowledge and skills. They can then seek help from their peers, teacher or other resources to address the gaps. Learners do not move onto the next unit of learning until they are confident they have mastery and can pass the assessment.

A variation of mastery learning is repeating assessments but with reduced support, where success becomes a learner being able to complete similar tasks over time with an increasing degree of independence.

3. Engage a wider range of people and perspectives in assessment, including learners and their families – and ensure that teachers are all “assessment literate” to lead this.

Some things to try:

Co-design of assessment rubrics and criteria charts – teachers and learners work together to design a rubric that describes success criteria and sets out what good looks like. Rubrics like this are often co-designed on the basis of shared examination of an exemplary piece of work, identifying and agreeing what makes it so good. Rubrics promote learner agency and empowerment by giving learners a sense of control over their learning and how they are being assessed.

Learner portfolios – portfolios and learning passports record learning in a variety of ways, for instance using narrative and photographs and annotated copies of learners’ work to give a clear and detailed perspective on what the learner has achieved and why this is important to them. Recently, digital tools have expanded the range of evidence and examples that can be collected in a portfolio, to include video, audio and presentations, for instance.

Exhibitions of learning – there is a long history of exhibition or performance as a means of making achievement visible and assessing it. Art exhibitions, drama or music performances, sport, chess tournaments – there are multiple examples. More significantly, there are examples in the UK and around the world of schools where exhibition and learner portfolios are the principal forms of assessment.

Final word

There is, of course, much more that we could add to this – and much more was contained in the Critical Friendship Group conversation from which this article was drawn. What all the suggestions have in common, though, is that they are driving towards assessment processes that facilitate growth, the exploration of oneself, deeper learning and self-worth. They are about creating – for all learners – hope for the future.

Acknowledgements

This article has been developed by drawing on contributions made in a Gesher School Critical Friendship Group by generous friends and colleagues who are expert in assessment and/or neurodiversity. They are:

Dr Amelia Peterson (London Interdisciplinary School)

Alison Woosey (Bolton Impact Trust)

David McVeigh (Head of Assessment Design at Pearson UK)

Kelly Sanders (Former USA school principal; consultant)

Joe Pardoe (School 21 and Big Education)

Joshua Gross (a neurodivergent school-experienced young person)

Anne-Marie Twumasi (Big Change)

We would like to take this opportunity to offer our sincere thanks for the time, energy and insight that each of our critical friends brought. Your advice and ideas are already making a difference.

The Role of Local Systems in Rethinking School

With thanks Veronica Ruzek, Director of Curriculum and faculty members across the Farmington schools.

As has been said in Holly’s introduction, there are three sections to each issue of this journal.

As has been said in Holly’s introduction, there are three sections to each issue of this journal.

The first is “Rethinking School”, and most of the articles do just that – imagine how school could function differently. However, schools don’t exist in a vacuum and this short piece focuses on the enabling role that the wider system within which the school is nested, can play.

In the final section, “Resources for Schools” you will find some inspiring project cards from schools in Farmington, Connecticut, USA – with many thanks to Veronica Ruzek, Director of Curriculum and faculty members across the Farmington schools for sharing them. Farmington Public Schools has a mission and vision statement to “enable all students to achieve academic and personal excellence, exhibit persistent effort and live as resourceful, enquiring and contributing global citizens aligned to our Vision of the Global Citizen”.

This Vision of the Global Citizen is worth sharing, partly because of the system leadership it displays – a bold, inspiring and invitational vision for all Farmington’s schools – but also because of the direct connection one can make with the moral underpinnings and student agency displayed in the Project Cards.

Read it, then read the cards, and the connection will be obvious.

What is Crew? We are Crew? Kvutzah at Gesher

Sarah Sultman and Bradley Conway

Valerie Hannon and Julie Temperley (both of whom have been good friends of Gesher School) recently published the book “FutureSchool”, which involved the identification and study of around 50 schools across the world that are doing exceptional things in the education of their young people.

There were a few features of note in common, and three are highly relevant for this piece. They are:

- Building a “team” culture of mutual support and ambition amongst and between learners.

- Creating a relational climate that promotes motivation and wellbeing.

- Knowing learners profoundly well, such that engaging learning can be personalised to their interests and passions.

These are foundational features of Crew, which is what this article is about.

What is Crew?

As parents, we know and value the relational qualities of primary education. Our children are taught largely by a class teacher who knows them really well – and they know that they are known. Parents know it, too.

Rod Allen, who co-hosts the podcast Free Range Humans: how can we make schools fit for human consumption? recently cited an experience from his daughter’s primary-class years. Her teacher loved photography and committed to taking a photograph of each child in her class illustrating who she felt each child really was. At parents’ consultation he and his wife were shown a photograph of their daughter in the playground with other children, which caused him to say: “I didn’t need to hear any more. It was obvious that this teacher understood our child and valued in her what we valued – Maths and English and love of learning – she was in good hands.”

Contrast this with the dominant model of secondary schools where a student is likely to be taught by between eight and 10 teachers a week (or more) for, at most, three one-hour lessons. Few youngsters will feel well known; many won’t even have their names known by all their teachers. Crew is an antidote to this.

Crew is a secondary (and primary) school approach that enables youngsters to feel profoundly secure and well-known by their Crew Leader. It occupies perhaps one hour or more each day, and there are three key features:

-

It prioritises relationships and wellbeing.

-

Knowing learners really well enables learning support to be personalised to student interests and passions.

-

It generates within the “crew” a community of mutually supportive learners. It is not a teacher and 25 students, but 26 learners and teachers working together with their different knowledge, experience and capabilities.

Put another way, Crew is two things. “It is a school-wide culture that supports social and emotional wellness, character development, and academic and life success for students and staff. It is also a unique and transformational meeting structure for secondary school advisories, elementary school morning and closing circles, and for staff collaboration.” Ron Berger, CEO of Expeditionary Learning Schools is considered to be the architect of Crew, and EL schools have been practising it for 25 years. The quote above is taken from the introduction to his book “We Are Crew”.

Ron Berger’s insight into the alchemy of Crew goes something like this: “If you are a member of a climbing team trying to get to the top of the mountain, that is only possible if the whole team makes it to the top. So, your job is to support every other member of the team to make it – and they in turn will be supporting you.” This is it in essence – a mutually supportive community that cares enough to support all members to success.

That is Crew. We are all crew, not passengers. This is Crew.

Crew in the UK

Crew is not part of secondary school culture in the UK. Traditionally, UK schools have short “form tutor” periods involving registration, administration and occasionally some personal and social education. This is nothing like the Crew model, which is at the heart of EL schools and a range of other US school designs. There, it is both a structural component and the foundation of school culture. It “serves as an ethos of inclusion: students strive to reach ambitious goals together as a community. They are responsible for their own wellbeing and their classmates’ wellbeing.”

One UK school that has made Crew foundational is XP School in Doncaster, for which the school maxim is “Above all, compassion”. XP is an Ofsted outstanding school, where inspectors remarked on features that relate to Crew: “Leaders are driven by the conviction that everyone can and should do well. Pupils are kind, generous-spirited and aware of the needs of others, both at school and beyond…..personal development and wellbeing are very well supported and pupils are taught to be considerate, kind and confident.”

Crew at XP is foundational. Students are aware of its impact: “At XP we are not just a school, we are a family,” and “It’s basically a metaphor for us all achieving our goals and we all do it together, so if someone falls behind we don’t just leave them,” and “We don’t just remember facts. We create memories.”

If you are not yet inspired, watch this video. As Andy Sprake (XP’s Executive Principal) says in it: “If you are going to make any difference to young people’s lives, you’ve got to know who they are.”

Crew or Kvutzah at Gesher – Its Origins

Gesher uses the term “kvutzah” instead of the word “crew”. As a faith school, this embodies the ethos, as Judaism is an insistently communal faith. Our sages tell us “do not separate yourself from community” and this notion of living our lives supported, enmeshed and emboldened by others defines our existence. The original meaning of the word kvutzah is “a Jewish communal and co-operative farm or settlement” but over the decades this has evolved into meaning the group you are a part of, or belong to. Urban Dictionary quite wonderfully describes its meaning as “a tight-knit group of crazy kids who spend summers together but will stay close no matter the distance”. And that is the purpose of kvutzah or crew at Gesher – to create a trusted community of people, a social collective where all voices are valued, bonds are created and everyone feels supported and understood.

There is a wealth of literature spreading across several disciplines that shows how important it is to wellbeing, to be surrounded by friends. Having people to talk to makes a difference. We speak of “unburdening” ourselves to others, and the metaphor is exact. There is something about human nature that makes troubles or concerns shared easier to bear. We are, as Aristotle and Maimonides said, social animals. What distinguishes homo sapiens from other life-forms is the extent and complexity of our sociality. Kvutzah encourages and champions this notion of respectfully sharing thought and feelings which in turn creates bonds between teachers and students; student to student, which in turn creates a culture of community at the school. (Adapted from Rabbi Sacks’ Community of Faith.)

The two statements below are taken from the “day in the life” created as a practicalisation of the school and community’s Blueprint vision for the school.

“At the beginning of every day we spend time together. Kvutzah is our secure base. The name provides the clue to how it works – we care about one another and pull together to help each other to succeed. We check in; have learning circles; plan our day, etc. Above all we focus on mindfulness, wellbeing and motivation. We focus our mind and collectively start our day, using tefillah/prayer to help us.

“School day also ends with Kvutzah when we are not out doing community projects. There is check-in and sharing and planning for extended and home learning. There is fun, too.”

It is no stretch of the imagination to understand that the diversity of need and talent amongst SEND learners makes something like Crew or Kvutzah essential. Autistic and neurodiverse young people need to be known; need to have their profile of behaviours understood and accommodated; need to feel valued and respected within a supportive community of peers; need to feel that they belong. This is even more important in a context where many young learners have had damaging prior experiences in mainstream schools.

Crew at Gesher in Practice

In practice, Crew time is an opportunity for the students to focus on, and enhance, any, and all, of the three key relationships in their life – their relationship with G-d; their relationship with other people; and their relationship with themselves. Through prayer, a daily review or quiet contemplation/meditation, the students work individually, and together, to enhance their own mental, emotional and spiritual wellbeing. They learn to care, share and be aware of their own needs as well as each other’s, which enables them to develop their compassion, collaborative skills and resilience – key attributes of life.

However, crew time at Gesher is not restricted to the students. Staff have their own form of crew time. Every week, a staff member chooses a key theme which permeates through three morning briefings and enables all staff to be aware, involved and connected with key aspects and events within Judaism, other faiths or none; within SEND or therapy; within education or their environment; and within the UK or beyond. Regularly enhancing our staff’s personal and professional development has had a profoundly positive effect on the camaraderie, cohesion and teaching within the school and ensures that everyone’s inspiration and passion is valued and shared.

Who is wise?

One who learns from everyone!

(Ethics of the Fathers 4:1)

Professional Prompt Questions

- Where Crew (or Advisory, or Kvutzah) is practised, there is a school-wide body of practice that supports it. Is that true of tutor time in your school?

- Watch the XP video as a staff or as a year team. What can we take from that to influence our own practice? What might be easy to do tomorrow?

- Do your staff “have their own crew time”? Should they? Could they?