Demystifying Project Based Learning

Loni Bergqvist

Loni is Founder & Partner at Imagine If, and is a PBL coach to Gesher School

There is a range of reasons why a school decides to break the mould of traditional education and embark on a journey of using Project-Based Learning (or PBL) as their primary approach to teaching and learning. Many schools are becoming increasingly aware of the skills and knowledge their students will need to thrive in their lives due to advancements in technology and society.

These skills include collaboration, critical thinking and communication among others. Other schools become interested in PBL because of a philosophical resolution that every single student, regardless of background or perceived academic ability, should be able to flourish in school. In this pursuit, schools are required to break the traditional model of “one-size-fits-all” approach to learning where everyone is doing the same thing at the same time in the same way.

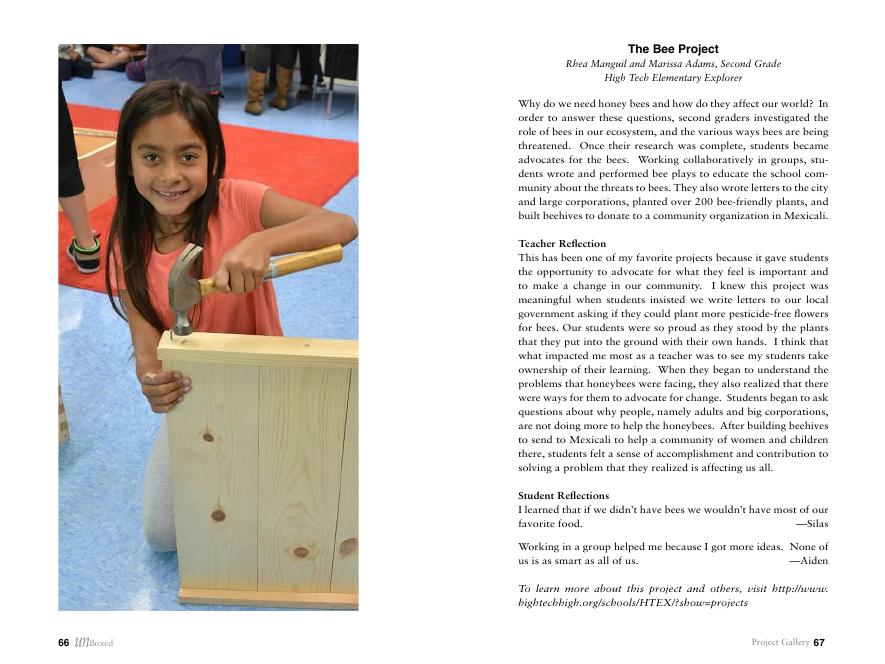

Instead, PBL offers the possibility for students to investigate real-world problems and challenges that are relevant to their lives. They collaborate in teams and develop their own solutions. Students are engaging with learning that matters to them and producing work that matters to someone else.

But itʼs not rocket science.

I often get asked, So, what exactly is PBL?

And the honest answer is: you already know.

Projects make up the world we live in every day.

When a daughter learns to play a love-song at her parentʼs wedding anniversary party. When film-makers make a documentary for a TV programme. When a lawyer takes on a new case. When we cook a meal for our family. Our lives are made up of little and large projects. When we are driven by a real need to create or do something new… we engage in Project-Based Learning.

But most schools are not set up to embrace learning in this way. To make this transition, teaching and learning must be organized around a set of Project Design Elements that help establish the basis for authentic work and natural learning processes while also, importantly, integrating academic learning goals.

Project Design Elements

Big Questions

Every project is composed around a Big Question that is designed to set the stage for the inquiry and exploration during the project. Big Questions are complex, found in the real-world and require students to develop their own answers over time. Examples of Big Questions include: How can we get our families to be more healthy? and “What is the perfect school?”

Student-Created Products

During each project, students create products. It is these products that drive the learning and inquiry process throughout PBL. Products can be physical (like a sculpture, poster or furniture) or virtual (like a website or social media campaign) and everything in between. In the process of making, we learn by doing and engage the head, hand and heart.

Drafting and Critique Process

Driven by creation, students go through a process of drafting and critique. They start by examining models of exemplar work and ask and answer the question, what makes a good (product)? They may need to brainstorm, draft a plan or do additional research as they start to make their products with their peers. With each new draft, feedback is given to improve the work. Sometimes this feedback is teacher to student, but it is often peer to peer or an expert guest from outside school who is relevant to the project. Through this process, students nurture a ʻgrowth-mindsetʼ, go deeper into their own understanding and application of academic knowledge and create a community of learners where it is the responsibility of all to produce beautiful work, and to support each other to do that.

Exhibition

Every project includes an Exhibition of learning where students present their work (product and process) to a public audience. This authentic audience is carefully chosen and is best when it includes members who require the knowledge and products created in the project by students. This might include a school-wide Exhibition night where the local community is invited, or a presentation at the local aquarium to inform the public about ocean conservation.

The Philosophy of PBL

While projects are planned around these Design Elements, there are foundational beliefs and philosophies that underpin PBL and are just as significant as the project. When these vital mindsets are in combination with great project design, PBL is transformative and truly authentic to learners.

Adults must believe that all young people are capable of amazing things. When the adults working around children hold limiting beliefs about what individuals are capable of achieving, when we use language like more able or less able, it becomes impossible to design learning experiences that allow all students to flourish.

Teachers must believe that learning is more than memorization. In our current education culture, most of us have been conditioned to believe that learning is about memorizing knowledge and we are ultimately successful in learning when we can transfer this knowledge onto a test or exam. School learning and the learning that is mostly required of us outside school are two different things. Natural learning (when toddlers learn to walk, for example) engages in a process similar to PBL. Itʼs messy. It requires failure. And itʼs not always easy to assess or find progress. But toddlers walk, and they exhibit it! When we shift our perceptions of what learning is, we can find much more of it and begin to value something else.

Finally, there must be a profound boldness to commit the primary purpose of school to be empowering young people to know who they are, what they are naturally positioned to love and to have the confidence to contribute to the world they are already a part of. It is the boldness to commit to every young person leaving school with their self esteem as a learner enhanced – to every child walking.

Loni Bergqvist is the Founder and Partner at Imagine If, a Denmark-based organization committed to support schools with using Project-Based Learning as a catalyst for educational change. Loni was previously a teacher at High Tech High in San Diego, California and has worked with schools to support the use of PBL since 2013.

Professional Prompt Questions

- How is your current curriculum preparing learners for the real world skills they need?

- What do young people really need to learn in order to thrive?

- How can you build a curriculum in which every child can thrive and explore and build their innate skills?

- How can you develop projects that allow your children to create authentic work?

- What does a really good, whole-person, learning process look like?