A Fireside Chat with Pani Matsangos: Headteacher, Westside AP School, London

This conversation with Pani was held with Zahra Axinn and David Jackson of The Bridge Editorial Team. Only Pani’s responses are attributed.This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Thanks for joining us, Pani. Ali Durban from Gesher visited Westside recently and was impressed, which led to this follow-up for The Bridge.

Pani: I know The Bridge; it’s a lovely publication.

Let’s start by hearing about Westside School.

Pani: Westside is an Alternative Provision (AP) school for secondary-aged children who have been excluded or are struggling in mainstream settings due to social, emotional and mental health challenges. We offer a tailored education for up to 70 students, currently at 55, delivering Key Stage 3 curriculum and GCSEs for Years 10 and 11.

Number one on our list really is engagement: first wanting to be in school, and slowly scaffolding the support that they need in order to get to remain in lessons, to engage in lessons, and to partake in a full school life, which also involves a lot of sport, art and culture at the same time, and broadening the notion of success beyond the academic. That’s really important to the children we work with. There has to be opportunity to win as often as possible, in as broad as possible a sense.

And the last thing I’ll say is about identity. The children who join us haven’t identified as students that can succeed at school, and we really need to flip that and to transform their sense of self. In this way we have tangible impact on the way in which they work and the way in which they engage with staff and achieve some sort of success.

Sounds like a unique approach. Gesher focuses on learner engagement too. How do you achieve that while teaching a GCSE curriculum?

Pani: The hook is about adaptive teaching techniques to keep students engaged. For example, we integrate game design into lessons, like weekly revision sessions for Year 11. They work in teams, moving through stations that test their knowledge. Collaborative learning is a core focus, especially with students’ social and emotional development. Additionally, we have Progress Leaders (PLs) who support students by understanding their individual needs and tailoring learning strategies accordingly.

Tell us more about the role of Progress Leaders.

Pani: They focus on enabling each child to become as self-sufficient in their learning as possible. It’s a coaching model. PLs act as coaches, guiding students toward autonomy in their learning. They are assigned to specific classes and work with each student throughout the day, building up data on their progress. This model moves away from the traditional teaching assistant role, instead fostering independence through continuous support and observation.

How do Progress Leaders assess where each student is on the journey to autonomy?

Pani: They gather and record data from daily observations, looking for patterns in behaviour and learning which can inform next steps. This helps them identify when a child is dysregulated and making impulsive decisions or choosing unwisely. We use this information to tailor support and determine the next steps for each student.

Is the teaching just subject-specific, or do you incorporate integrated learning? Do teachers collaborate in planning?

Pani: We do both. For Year 11, we’ve integrated collaborative planning across subjects, like English, Maths, and Science, to engage students in cross-curricular activities. For younger students, particularly Years 8 and 9, we focus on personal development lessons that address their social and emotional needs. We also have a strong culture of collaboration among teachers and PLs to meet each child’s needs.

You’ve mentioned building trust-based relationships with students. How does that shape your school culture?

Pani: Trust is fundamental. We understand that disruptive behaviour often stems from unmet emotional needs, so staff work to build empathy with students. This strengthens relationships and creates a supportive environment. We believe in a long-term approach–lessons are just one part of helping students grow and develop.

Could you elaborate on your definition of inclusion?

Our definition of inclusion underpins everything. We look at inclusion in a three-tiered way.

I. The first is inclusion within the school – making sure that each child is able to feel included in the school, via adaptive teaching, strong relationships, and having a broad notion of success outside the academic and strong parental relationships, so that they realise that school is for them.

II. The second is functional inclusion outside school – how they communicate with people, how they have the confidence to try things out, how they regulate themselves in tricky situations. It might be going to a museum. It might be going to a sporting activity outside school. We explore what inclusion means outside Westside School.

III. Finally, we’re working hard on the third, longer-term inclusion beyond Westside. This is inclusion in an impact sense. Are they able to use their voice to articulate their needs, and to effect some sort of positive change, beyond 16 and beyond Westside.

Your personal story seems to connect with the work you do. What led you to alternative provision?

Pani: Professionally, I saw mainstream education failing to address the needs of marginalised students. I wanted to better understand those children. We know that the numbers are huge, almost 10,000 exclusions last year.

On a personal level, I have a sibling who was a child who struggled tremendously at school, and eventually, a few years ago, that became a really difficult circumstance. He became a rough sleeper, and he had significant mental health issues. When he passed away, I started to think. Regarding his autism, from a young age he didn’t have the support that he needed, and you can see how things compound negatively. Needs are not met over the years. With the right interventions early on, I think there’s a great deal that can be done to support young people who think differently or have had adverse child experiences. I think you can unlock a lot of positivity and a lot of potential just by thinking differently about the way in which we work. And so that was important for me to join AP and to work in a way in which we’re working now at Westside.

Thanks for sharing, Pani. Do we need more quality AP provision or for mainstream schools to better meet the needs of all children?

Pani: We need both. Some students thrive in smaller settings, which allow for more tailored support. While mainstream schools can’t always offer that level of attention, they could benefit from adopting the inclusive strategies we use in APs, especially around data-driven decision-making to better understanding the underlying factors inhibiting a young person’s social and emotional growth and development. This is of course a lifelong journey and applies to us as adults.

Our journal, The Bridge, was established as a way of seeking to share the practices evolving at Gesher and other interesting schools – like yours. Is Westside an island of excellence or is there also a mission to influence others?

Pani: I think there’s definitely a mission – hence this interview. There’s a national need to rethink how we approach education for students who don’t fit the traditional model. It’s just a really tragic story ultimately that we have this sort of pipeline to prison scenario. The accountability measures of mainstream schools often fail to meet the needs of these children, leading to exclusion.

And there’s also the issue of low expectations. We talk a lot about expectations in schools and there is this idea that children should be sitting behind a desk compliant and quiet and working really hard. And, for me, that’s also low expectations in some ways, because high expectations should be about developing independence, developing, understanding of self and working with others and, and wanting to be curious about things and not having that sort of drummed out of you.

What is your success rate, and how do you measure success?

Pani: Of course, we’re not universally successful. It’s a dynamic process. Success isn’t guaranteed, and the challenges evolve. But we remain adaptive, constantly evaluating each student’s journey. We focus on success in school as the first step—if a student can engage in learning and feel included, that’s a meaningful measure of success.

Are there any final thoughts you’d like to share?

Pani: Absolutely, yes. The core purpose of education should be about fostering curiosity, independence, and emotional intelligence. We need to shift the conversation about what education is for, and stop focusing as much on compliance and linear models for learning, accepting that learning is a complex and messy endeavour! Each person in school, or connected to the school, whether it’s someone in our HR team or the canteen, or a visiting speaker or external mentor is someone that could make a difference to that young person’s life. That’s something that we’re trying to create here, because why not? We ALL have a part to play in raising our children.

Thank you very much indeed, Pani.

Pani Matsangos is the Headteacher at Westside School, an Ofsted Outstanding Alternative Provision (AP) school serving pupils across London. With almost 20 years of experience in mainstream education, he is deeply committed to supporting children with special educational needs, mental health challenges, and difficult home circumstances. Drawing from both formal training and personal experience–having managed his own SEN and a complex upbringing–Pani champions inclusive education. He ensures pupils access a high-quality traditional curriculum enriched by arts, sports, and culture, broadening the definition of success so every student can thrive, both academically and through diverse, life-enriching opportunities.

‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever.’ John Keats

‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever.’ John Keats

What if…

What if…

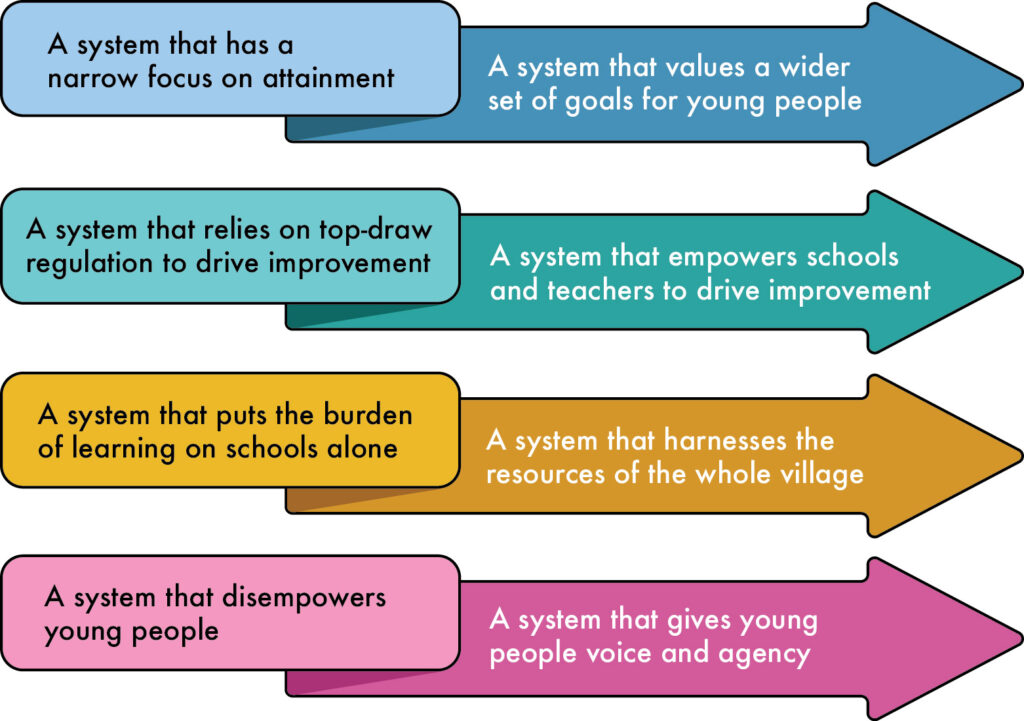

The order in which the four shifts feature is also important. The first shift, from a system narrowly focused on attainment to one that values a wider set of goals, is the ‘crucial cog’; the magic key that will unlock all others.

The order in which the four shifts feature is also important. The first shift, from a system narrowly focused on attainment to one that values a wider set of goals, is the ‘crucial cog’; the magic key that will unlock all others.