Assessing What Really Matters

A conversation with Ron Berger

In March 2022 some staff and friends of Gesher School met with Ron Berger, Chief Academic Officer at Expeditionary Learning. Ron is the author of 11 of the most valued books about educational leadership, learning and relationships in schools. We talked about what really matters when assessing young people, especially those who are ʻdifferently ableʼ, and what good assessment can mean for supporting happy, fulfilled and kind future generations.

Why aren’t traditional forms of assessment right for children?

Ron Berger

The first thing I would say is that the most important assessment that’s happening in a school is never high stakes tests, or even interim tests, or even weekly tests. The most important assessment that’s happening in a school is what’s going on all day long, every day inside the heads of kids, because every kid in every school is assessing, all day long, how much she understands, how well she’s behaving, how much she wants to try, how good she feels about her identity – her academic identity and her personal identity. When she’s about to hand something in, she thinks, ʻIs it good enough?ʼ She’s in class and she thinks, ʻShould I raise my hand? Do I understand this stuff fully?ʼ When she looks at her personal relationships, she’s always assessing ʻAm I a good enough person?ʼ That kind of assessment is constant. It’s constant in all of us.

And that’s the kind of assessment that matters the most. Of

course, we need to check in on kids’ skill levels sometimes,

just like every year we should go in for a physical and make

sure our body is working and that our vital signs are okay.

And, if there’s something wrong in our annual physical,

that’s something we need to attend to. But an annual

physical tells us nothing about how to live a good daily life,

right? It doesn’t give us feedback. We need to be our best

selves academically and personally and physically. And it’s

the lifestyle choices we’re making all day long about what we eat and how we eat and how much we sleep and how

much we exercise and what our relationships are like with

others that define whether we have a healthy lifestyle or

not. And we are assessing that all day long.

We need to remember our kids are also doing that all day

long in school. And so we need to build systems of

assessment that encourage them to be their best academic

selves and to be their best personal selves all day long,

where they’re getting clear feedback from each other and

from themselves about ʻHow am I doing? Do I understand

this well enough? Can I show more academic courage? Can

I take more academic risks? Can I put more effort into this?

Can I take the risk of showing what I don’t understand? Can

I step up for other people? Can I be a better person?ʼ

So, of course, we still need to have those interim

assessments and quarterly assessments and annual

assessments, just like we need to go to the doctors’

sometimes, but assessments that give us ways to monitor our

own academic and personal health all day long are the

assessments that will really make us better students and

better people.

Gesher and Standardised Forms of Testing

Rowan Eggar, Assistant Head Teacher, in charge of assessment

One of the things that we are really struggling to navigate is the way our UK education system is built around the notion of standardized testing – which can be quite fixating.

We find that parents, especially those whose children have additional needs, use milestones like GCSE grades as a marker to show their child has made relevant progress, which is entirely understandable. But one of the things that we are trying to do at the moment at Gesher is to also support our parents and children to focus on life skills and the journey it takes to become fully fledged humans in society. You canʼt determine this from standard grades and scores.

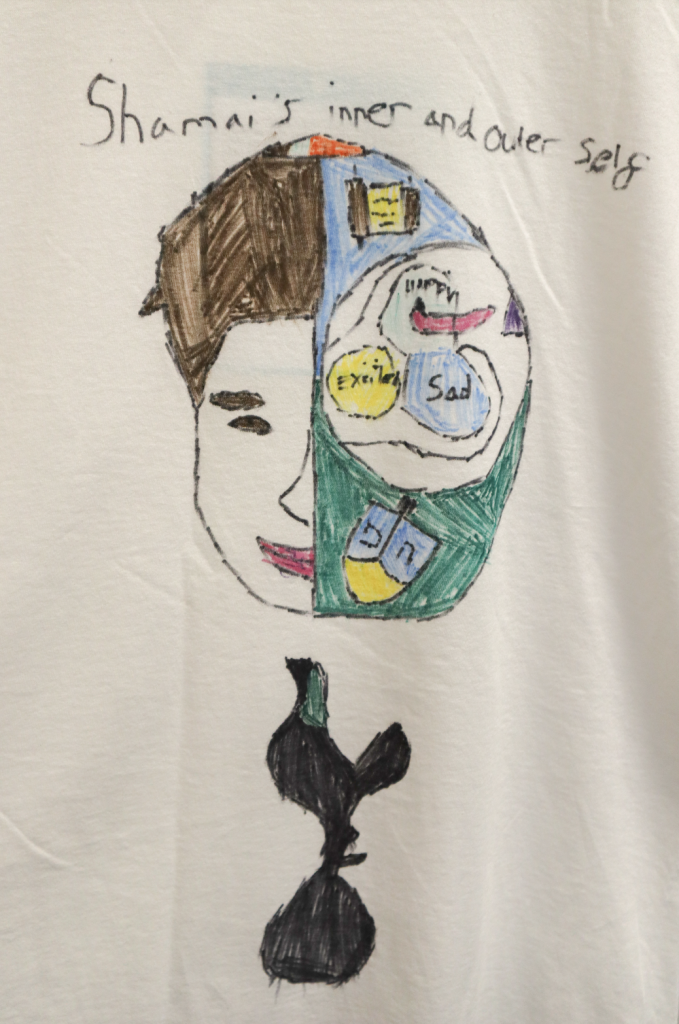

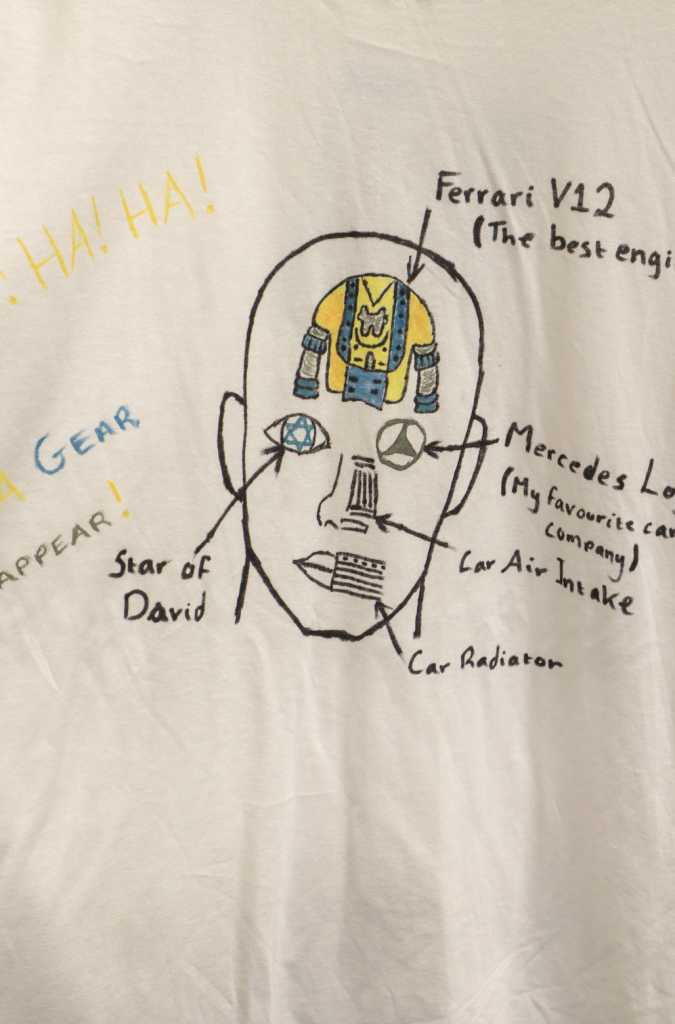

We are looking at things like personal and emotional health, self-care, wellbeing, things that maybe our children struggle with more, and starting to build in assessment approaches that encourage them to check in with themselves, very similar to some of the questions that you mentioned, Ron. Lots of our students don’t yet have the toolkit to ask themselves those questions. So this type of assessment needs to be taught in a more obvious way than you might in a mainstream setting.

Loni and I are currently working with a few colleagues on an assessment tool that breaks down the national curriculum into small steps for whole-person assessment. One of the elements of this is around life-skills. Our SENDCO and Assistant have developed a ʻlife-skillsʼ programme, where our children get different badges, bronze up to platinum, depending on the life-skills they are building.

Whatʼs a bit more of a struggle is thinking about assessment for personal traits and character traits. Often our childrenʼs academic progress doesn’t really reflect who they are as people and how much they’ve grown. So, let’s say they’ve grown in confidence to be able to communicate, academic progress might not show that. Weʼre developing a tool that is about personality and character, but thatʼs a work in progress!

What advice would you give to a school embedded in the current assessment culture that wants to move to a new paradigm of thinking about assessment, one that focuses on the wholeness of the strengths and skills of children?

Ron Berger

That’s a great question, because we are all under the same pressures.

I find it really interesting to hear what Rowan is saying about being a school

that’s working with differently abled kids, but there is still the same kind of

intense pressure around labelling and ranking that every other school

experiences.

It’s pernicious and harmful for all kids, but it’s particularly harmful for kids

who always get ranked in a way that doesn’t make them feel positive, and

that doesnʼt focus on their personal identity as a student and as a person.

Imagine if, as adults, we got ranked every day in our life, and we were

always at the bottom of the rankings. What would that do to our spirit in our

work, in our lives as, as people?

I think anything that our schools, and particularly a school like Gesher that’s

working with differently abled kids, can do to keep ranking out of that

conversation is important, because being ranked low on any scale hurts

your spirit. It makes you lose your heart for investing and taking risks.

Kids are also aware of the way the world sees them and the kind of rankings

of the world. So being a school that lets kids know that those types of

rankings arenʼt their priority is really important. Schools should prioritise

and share work that focuses on what kids are learning, through portfolios,

projects, presentations – assessment approaches that celebrate different

types and styles of learning, building on the strengths and positives about

each childʼs learning.

But itʼs important that that type of assessment also shows kids where they

need to work on their challenges and the steps that they need to take next.

I think it’s fine for kids to be able to be honest about the things they struggle

with, whether those are personal things, executive functions, physical or

emotional wellbeing, as well as academic levels.

Ron shares a story here, which can be watched via the QR code at the end of the article, or link.

Ali Durban, Co-founder of Gesher School

I love that. I think as Rowan said, one of our biggest challenges is working in a system that both feels familiar and safe and also gives parents some kind of validation that their child is going to be okay in the world emotionally. Itʼs hard because our children havenʼt become adults yet, so we canʼt yet show that this way of learning and assessment is going to let them shine. Going on a journey like this is ultimately about trust.

Loni Berqvist, Project Based Learning Coach at Gesher School

We have a tendency to try to assess everything that we put value on. Is there a risk that we start to try to assess childrenʼs passions and the impact theyʼre having as humans, say, by creating portfolios that demonstrate the impact they are having on the world, which could kill the passion? How do we move to a place where weʼre comfortable with not having to assess things and demonstrate outcomes in the ʻnormalʼ way?

Ron Berger

I love, Loni, where you went at the end of your question, “assess it in that traditional way”, because I actually think it’s fine to assess everything. If it’s a reflective and formative assessment, if it’s an assessment to help us learn and understand, and it’s not a ranking, judging, summative assessment, then I don’t think it’s bad.

I feel like kids and adults assess everything we do, right? If we watch a TV show, we assess it afterwards, we discuss, what did you like? If you put on a new outfit, you’re going to assess, do I look good in this?

You’re always assessing and making that assessment explicit and reflective and thoughtful and safe is fine. I don’t really worry about us assessing many things. It’s the way we assess them that matters.

But assessment in the traditional sense – where we need a summative number next to this, we need a letter next to it, we need a ranking next to it – is where we kill the spirit of assessment.

So, going to a silly metaphor, if you see a movie, it doesn’t diminish the movie to say, “Wow, that was amazing, where did it work for you? Where did it move you?” But what kills that passion and fun is asking, “Okay, of all the movies you’ve seen in the last three years, where does this one rank? And do you give it an 82 or do you give it a 65.”

That kind of assessment, where it has to be summatively labelled and viewed in a reductionist way, so that it could be ranked along with a set of other movies, stops it being fun to even talk about it. But assessing it qualitatively through reflecting in a safe way is something that we can do with all kidsʼ work and all kidsʼ stuff. They are always doing it anyway. It’s just making it more explicit: ”Let’s have a conversation. How are you doing with this?” Whether it’s a life skill, whether it’s emotional growth, whether it’s physical capabilities, or whether it’s academic doesn’t matter, kids can assess “I’m doing better at this, or I’m not doing better. Why?” That’s very different from saying, “We’re going to rank you. We’re going to give you this label”. That’s scary and threatening but assessing how you’re doing doesnʼt have to be.

Gesher is underpinned by Jewish principles. What does having that foundation bring when assessing children as whole people?

Ron Berger

Well, in particular order for Gesher, there are three reasons why assessment that lifts the whole child and helps the whole child to feel like she’s growing into the kind of person and scholar that she wants to be are important.

The first of those is that it is a school particularly for differently abled students, which means they go through all of their life getting negative messages, telling them that they are not ranking as other people would. There are so many ways in which life is giving them the message that they are not good enough, whether it’s about their social skills, emotional skills, physical skills, academic skills. There’s a tremendous reason for Gesher to use an approach that gives kids power and pride in getting better at what they are rather than feeling diminished about who they are.

So having an asset-based vision of assessment at Gesher for that reason is extraordinarily important. Itʼs important in every school, but particularly important in a school that needs to lift kids who people have seen with a deficit lens, for so much of their life.

And the second reason it’s an important thing for Gesher, is that as a faith-based school, everyone who chooses to send their child to Gesher knows that there is more to life than academics. There is the human character of who you are as a human being. You choose to send your child to a faith-based school because your faith, your culture is something that matters to you, because you want your kids to embrace values that you care about. And those values mean being a good person. And so if the assessment systems diminish the kind of human beings we’re trying to create, they’re not good for us.

We need assessment systems that help our kids become more of the kind of people we want them to be. And so kids should be self-assessing and should be getting assessed for beyond their academics. It should be a holistic assessment system because kids should be proud to say, “This is the strength I have in this, and this is where I need to grow in my character.”

They should be able to say, “I’m focused on improving my courage, my passion, my respect, my responsibility, my kindness, my initiative, my integrity.” Kids should be assessing themselves and thinking about, “How do we become better human beings?”.

Itʼs scary for schools that are not faith based to say that because how do they choose which values theyʼre supporting? Will parents get upset, as they may not feel the values of the school are their values. For me, that’s a ridiculous cop-out and it’s just not real. I think almost all of us as human beings share values. What parent does not want their child to be respectful and responsible and courageous and kind and have integrity and honesty? No faith, no difference, no political party, no background makes you disinclined to want your kids to be a good person in those ways.

A third reason is that schools have no choice but to teach character. Schools are already teaching character all day long because the way kids experience school makes them more respectful or more responsible or more compassionate or less. So the experience of schooling shapes who kids are, and we’re doing it intentionally and well or haphazardly and poorly. In summary, a faith-based school has the opportunity to lean into these things and say, we’re going to do it intentionally and do it well because we want good human beings coming out of this school. And we’re not worried about talking about values because that’s partly why people choose to attend our school. So, for all those reasons, I think having an assessment system that elevates the whole person for every child is a perfect fit for Gesher.

Ron is responsible for leading EL Educationʼs vision for teaching and learning, bringing with him over 45 years of experience in education, 28 of those as a public school teacher.

Ron has authored 8 books on education: A Culture of Quality, An Ethic of Excellence, Leaders of Their Own Learning, Leaders of Their Own Learning Companion, Learning that Lasts, Transformational Literacy, Management in the Active Classroom, and We Are Crew: A Teamwork Approach to School Culture. He is a sought-after keynote speaker nationally and internationally, focusing on quality, craftsmanship, service, and character.

Ron works closely with the Harvard Graduate School of Education, where he did his graduate work and taught the course Models of Excellence, focused on using student work to improve teaching and learning. He founded the Models of Excellence EL website, which houses the worldʼs largest curated collection of high quality student work.

Professional Prompt Questions

- What purpose do your current forms of assessment serve for children as future citizens?

- How would you assess the life-skills that children are learning under your care?

- What values would you assess children for?

- Who would you need to convince to move away front he current assessment paradigm? Yourself? Parents? Colleagues?

- How could the above align with standard forms of assessment, such as GCSE results or OFSTED grades?

Ron Berger – Additional Content from Gesher School on Vimeo.

Last year was an enormously busy year for us at Gesher and for our community as a whole. As we start 2023 and reflect on the achievements of 2022 there are two members of the Gesher community we would like to extend a special congratulations to. Firstly, Rama Venchard, our Chair of Governors, who received an MBE in King Charles II’s first New Years Honours List for his services to education. And secondly, Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis, who has received a knighthood in recognition of his interfaith initiatives, work with the Jewish community, and involvement in education programmes, of which we at Gesher have been lucky enough to be a part of. Mazal tov from Gesher!

Last year was an enormously busy year for us at Gesher and for our community as a whole. As we start 2023 and reflect on the achievements of 2022 there are two members of the Gesher community we would like to extend a special congratulations to. Firstly, Rama Venchard, our Chair of Governors, who received an MBE in King Charles II’s first New Years Honours List for his services to education. And secondly, Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis, who has received a knighthood in recognition of his interfaith initiatives, work with the Jewish community, and involvement in education programmes, of which we at Gesher have been lucky enough to be a part of. Mazal tov from Gesher!