Creating Better Schools by Design

David Jackson

Ask most people to draw a house and nine times out of ten the house they imagine will be a square box, with four square windows, a pitched roof with a chimney, and often some smoke curling into the sky.

We share a mental model — a blueprint — for what a house is and should look like. We don’t stop to wonder:

- Does our house have to be square or could it be a different shape?

- Should it be one storey high, or two, or three?

- How many windows of what size should there be, really?

- What purpose does the chimney serve?

Our shared ideas about schools are fixed in much the same way.

There are variations, but our mental model for school tends to include classrooms, corridors, rows of desks, students grouped according to age, one-hour lessons, subject teaching, tests, and so on. This model is based on schools designed in the past. We don’t stop to question whether the school, which we are after all drawing in the C21, should be — needs to be — very different from the blueprint created decades ago. We might ask:

- What ideas about learning are informing the layout of our school? What might classrooms look like if we thought of them as places where great learning can happen?

- Does all learning need to be packaged into ‘subjects’?

- Are one-hour lessons the best unit of learning?

- Is one teacher with 25 students better than two teachers with 50 students?

- Why are all students assessed at the same time when they mature differently?

- Do we have to assess by written exams emphasising memory?

… and so on.

Designing a new school for real is a chance to ask questions like these, and to ensure that the new school is more than just an improvement on the existing model.

“Gesher undertook a serious school (re)design process that placed the needs of their students at the heart of decisions about their new school design.”

At Gesher School, staff, students and parents know how badly a change to the model is needed because most of Gesher’s learners have struggled in schools like the one most of us would draw. So, Gesher undertook a serious school (re)design process that placed the needs of their students at the heart of decisions about their new school design.

Gesher was transitioning from a highly successful primary school to becoming an all-through learning community and needed to find a new school building and facilities, recruit staff, create a secondary school curriculum and reframe its mission and identity.

The leaders of Gesher School knew they needed to go way beyond improvements on the existing model, to design a whole new way of thinking about and doing school, in ways that learned from and built on their experience with primary-age children. They asked:

How might we design an all-through school that will offer success, enhanced self-esteem, personal efficacy, and progression opportunities for all our young people?

Secondly, in doing so, how can we involve multiple stakeholders in our design process?

Thirdly, how might we stand on the shoulders of existing practices around the world?

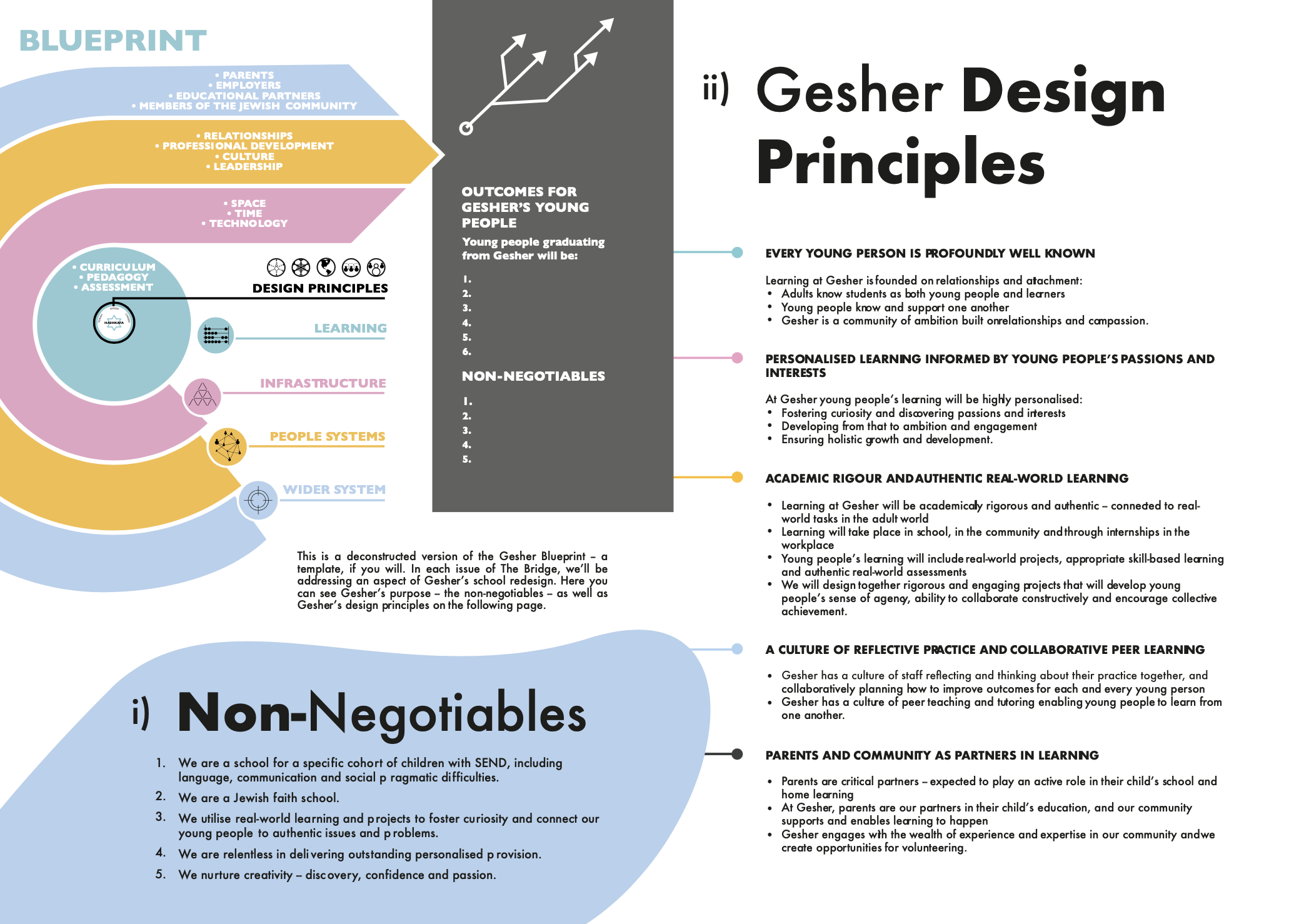

The design process that Gesher School entered into comprised eight workshops, each involving different stakeholders, which resulted in a school blueprint for:

- A bold vision and purpose; and

- A set of values-based design principles; which were

- Brought to life in plans for a range of innovative features that add up to a very different kind of school.

Upwards of 100 school staff, parents, students, community members, and other local stakeholders contributed to this seriously intentional and inclusive school design process.

Each issue of The Bridge will address an aspect of Gesher’s school redesign process. This issue focuses on the first two of the eight school design workshops that Gesher School undertook, which concerned (i) purpose and (ii) design principles.

(i) Purpose

Gesher’s discussions about purpose started with identifying their ‘non-negotiables’. Non-negotiables tell everyone what is and is not on the table; what is and is not within the scope of the school design team to change. Examples might be ‘no selection by ability’ or ‘the school will be co-education’ or, in Gesher’s case:

- We are a school for a specific cohort of children with SEND, including language, communication and social pragmatic issues.

- We are a Jewish faith school.

- We utilise real-world learning and projects to foster curiosity and connect our young people to authentic issues and problems.

These clear non-negotiables influenced design features relating to Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) provision, to faith observance and understanding, and to the design of curriculum and pedagogy.

A further key defining issue for Gesher to articulate was purpose – the vision and outcomes to which the school community would aspire. Being clear about what the school had to achieve with and for students; about the purpose of learning; about what matters for the community of the school — staff, students and parents – was an essential bedrock of the design process.

Within the current system, aiming for good examination outcomes is a given, and if that was all that mattered, then job done. However, during the workshop, through extensive discussion – and many post-its – it became clear that exam success on its own was not nearly enough. In brief, the outcomes Gesher agreed are that young people should become:

- Skilled for the future workplace

- Qualified for the next stage (exam results plus)

- Independent learners

- Confident in their sense of self

- Builders of meaningful relationships

- Ethical and responsible citizens.

These, one might hope, could be purposes shared by most if not all schools, but two things qualify them as exceptional in Gesher’s context. The first is the inclusiveness of the intent. They are purposes for all students, regardless of their prior educational history or unique needs. The second is to remember that Gesher is a school for children with identified SEND needs, most of whom have been unable to thrive in mainstream schools.

“Staff engaged with mini-case studies of interesting and successful schools around the world to draw from them the particular design features that inspired them.”

(ii) Design Principles

Workshop two was exclusively concerned with design principles and involved staff at the school considering the question: What would be the design principles or features of a school that can confidently achieve these outcomes for all its learners?

Staff engaged with mini-case studies of interesting and successful schools around the world to draw from them the particular design features that inspired them. They used this as a basis to shape their own, then tested the resulting principles they created together using personas of children at Gesher, asking: Would this work and how would it work for Amy or Peter?

Next Time — Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment

Agreement on these three components — the non-negotiables, purposes and design principles — precedes work on designing the more practical features of a school. Clear purposes provide a constant reminder of exactly what we aspire to achieve with and for learners and their families. Design principles provide the guiding architecture that relates to these purposes. They are ‘laws with leeway’ that frame what we do and how we do it. They are also the features that unify and inspire those who work in a school, and they guide and discipline decision-making.

With these three in place, the design process moves to consideration of the curriculum, pedagogy and assessment practices that will be informed by and consistent with the design principles and which will enable every student to achieve the outcome ambitions. That is for next time.

Designing New Schools in the USA

In America, there is a long tradition of creating new school designs. Some of the most successful schools in the world have been created in this way – Expeditionary Learning schools; High Tech High (some of whose resources we share later); Big Picture Learning schools; New Tech Network are all examples. The Gates Foundation alone funded more than 2,500 ‘small school models’ across the United States, and New York alone has 200.

Not all of these new school models have been equally successful, of course. However, their students consistently outperform their peers in conventionally sized and structured high schools with comparable demographics. There are some common design features across the majority of these models — and they are very different from the conventional UK school — they all:

- Focus on the centrality of relationships and personalising learning — have ‘advisory’, where advisory is the soul of the school, symbolising relational support for students

- Include project-based learning, an engaging and empowering pedagogical model, which also requires teachers to collaborate as designers of learning

- Have a pervasive cultural identity and school-level ownership of what matters, including what is assessed and how and by whom it is assessed

- Facilitate powerful and sustained adult learning.

The Cost of Not Having New Models in the UK…

Not to foster innovation in school design means that we constantly focus on striving to improve the existing school model – a model more than 100 years old and out of date.

It is a model with multiple features crying out for redesign. For example, it has failed to achieve equitable outcomes, or to address socio-economic challenges, or to engage disengaged learners — or to fully engage most learners, for that matter. Nor has it provided teachers with an intellectually challenging profession, or excited and involved parents around the experience of their children.

Professional Prompt Questions

The design process described above is effective applied to existing schools as well as new ones — revisiting purposes and design features together as a prelude to reviewing wider practices. Might this have value for your school?

The review detailed above distilled six clear outcomes that Gesher is committed to evidencing for all learners. Does your school have similar clarity about its purposes?