Reimagining Assessment: Views From an Autistic Young Person

Joshua Gross

Since the 1990s, the way we assess young people has been dominated by a culture of public accountability and competition, leading to the unhealthy belief that the grade is everything. The idea is now so important that many exams, like GCSEs and A-Levels are referred to as “high-stakes” tests because of the way they determine the next stage of someone’s life.

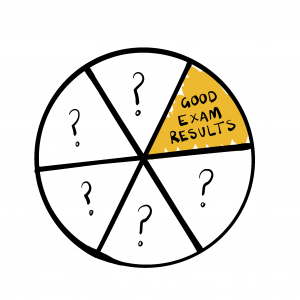

Those who create the high-stakes assessments claim that they are the fairest and most rigorous tool we have to demonstrate student achievement. However, the evidence used to back up these claims is often insubstantive (Richardson, 2022). One of the consequences of these high-stakes assessments is that young people’s outcomes are reduced to a number or letter which only reflects a very small proportion of their experiences and achievements at school and usually only in academic subjects.

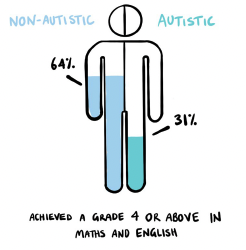

Whilst this affects all young people, data has shown that, on average, autistic young people do not achieve the same levels of academic success as their non-autistic peers assessed in this way. The most up-to-date government data shows that 64% of non-autistic students achieved a Grade 4 or above in Maths and English, compared to 31% of autistic students – and this data is not a one-off. The same pattern exists in the previous three years’ data. While the statistics alone are striking, even more profound are the hidden stories behind the data. As such, in this piece, we share the reflections and experiences of Joshua, an autistic young person who has the lived experience of feeling let down and misrepresented by the current system and who has vital ideas on how it might be reimagined to prevent the same thing happening to others.

“The big problem with existing assessments is that they are the be all and end all when you leave school.” Joshua

The same idea is expressed in the opening sentence to this article and yet what this means for young people can often get lost in the statistics. For Joshua, who at the time of writing is applying for apprenticeships, the implications are clear.

“I can only put my grades, not the fact that I spent most of my A-Level time suffering through extreme mental health issues and that it was a miracle I even made it to sit the examinations, not the six times I almost dropped out and came back to them later… It becomes really difficult to come out the other side and still be a strong candidate when the only important thing is what grade you got.”

Joshua’s solution to this problem would be for schools to recognise the skills that young people have through a more flexible approach to curriculum and to assessment. In Joshua’s case, he has a talent and passion for computer programming and, while he was able to take this as an A-Level, he was still assessed within the constraints of that curriculum and the conventions of exams.

“In my A-level computer science class we had people who had never opened the Python Editor before and we had people like me who had made full video games in one day before… I would be running off doing these ultra-complex things at home that would never be recognised because they weren’t even remotely related to the curriculum. Like, I can make a video game using languages that the curriculum doesn’t even know exist. And I’m just sitting there doing these things, but none of them get recognition. I can do all this stuff and it doesn’t matter because it wasn’t what I was told I had to do. I didn’t fit that specific guideline and therefore it’s not good enough.”

By having a curriculum that is less constraining, less of a rule book, there would be more scope for teachers to work with young people in their area(s) of interest and strength, aligned with their passions. While this would have benefits for all learners, there would be particular benefits for some autistic young people who often have a special interest or aptitude. Recent research by King’s College London, for example, has shown that when adults are accepted as having a special interest, and where it is responded to positively, recognised and valued, this can lead to them excelling in the linked curriculum area (Wood, 2021).

As not all neurodiverse young people will have a special interest that can be assessed within school, it is also worth considering other ways in which a more flexible assessment process would be beneficial. Here, Joshua has further important ideas to share.

“Assessment as it is now is not actually really a test of knowledge, but more a test of memory. I found often that those kinds of assessments really did not work for me, but one that I really excelled in were the two B-techs that I took in Business and Digital Media. Instead of having this one assessment that you’re building up to and studying in unhealthy ways for, you’re working on it throughout the entire course. It’s not one giant thing, it’s a bunch of smaller things. Break one big problem down into a bunch of smaller ones, and suddenly it becomes less of a big problem.”

Joshua’s views about coursework are echoed in the academic literature, which has shown the pedagogical benefits of such forms of assessment, as well as the fact that students prefer it to exams (Richardson, 2015). Despite this, under the current assessment system in England, none of the Maths, English or Science GCSEs have a coursework component which counts towards a student’s final grade. As such, the work that a student does across two or three years of study is condensed and assessed through a few hours of exams. This in turn then shapes their future opportunities. Joshua considers this system to be a particular challenge for autistic young people as “Often the pressures of the school system can break a student so easily and so quickly. And it becomes really difficult to come out the other side and still be a strong candidate when the only important thing is what grade you got.”

There are two more things that we know about the lack of fit between the current assessment system and neurodiversity. One was well articulated by Joshua: “If you emphasise ‘standards’ and ‘standardisation’, then by definition this will not work for autistic young people who are, by definition, non-standard.” The other, which is linked, relates to the idea of “spiky profiles”. Autistic learners are less standardised, less conventional – they have great strengths alongside different challenges. An assessment model that emphasises the challenges (e.g. writing essays) and minimises the strengths and passions (e.g. technical capability, creativity) will serve both autistic youngsters and the system badly.

Endnote

Joshua’s views are those of just one student, but the dearth of autistic voices in both the academic and non-academic literature in this field makes this a provocative contribution and one that we hope is built on by further activity in this area.

References

Richardson, J. T. (2015). Coursework versus examinations in end-of-module assessment: a literature review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(3), 439-455.

Richardson, M. (2022). Rebuilding Public Confidence in Educational Assessment. UCL Press.

Wood, R. (2021). Autism, intense interests and support in school: From wasted efforts to shared understandings. Educational Review, 73(1), 34-54.

Professional Prompt Questions

What rings true for you in Joshua’s comments?

You will almost certainly have neurodiverse learners in your school. Might a small piece of research or a focus group with them help to unearth challenges they face to which you could respond?