Leaving Learners in the Dust

Authored from the outcomes of a Critical Friendship Group discussion on Assessment, November 2022

Assessment, neurodiversity and some ideas for how schools can do better

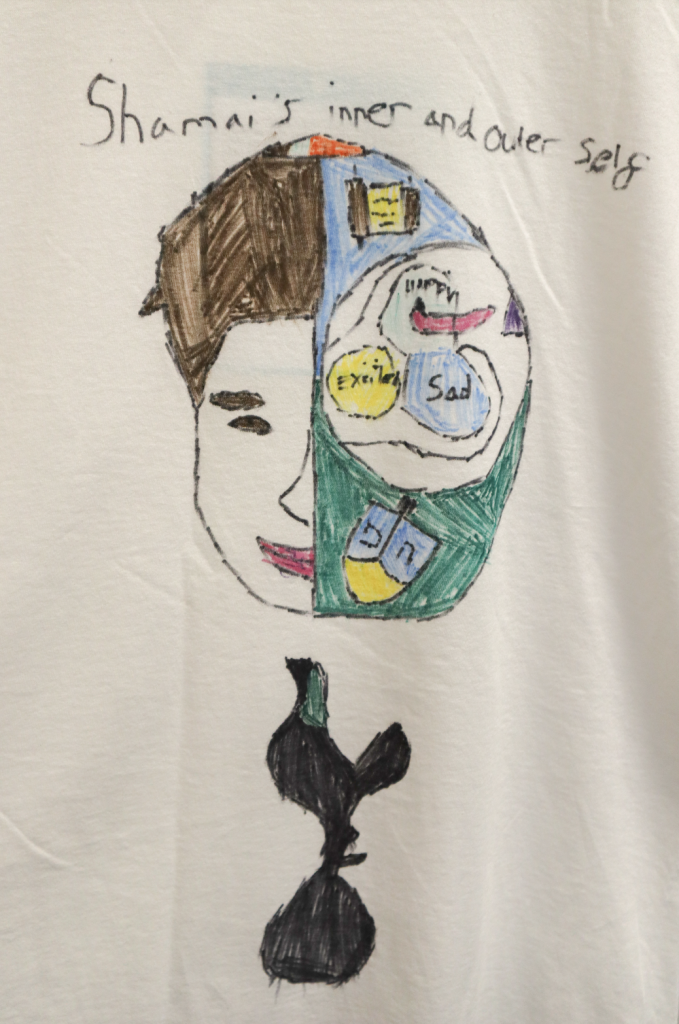

For the team at Gesher School, who are committed to personalised, project-based and real-world learning for students with neurodiversity, finding appropriate, reliable and motivational ways to assess learning and to provide the feedback and recognition of learning that learners need to progress is an ongoing and very practical challenge.

Joshua, a recent graduate from sixth form college, explained his experience with assessment – on this occasion his A-Levels – like this:

“The big problem with existing assessments is that they are the be-all and end-all. You either fit the mould or you don’t and, if you don’t, you really are kind of left in the dust. Most people don’t fit the mould – and especially neurodiverse people don’t – so that does lead to problems.”

Unfortunately, Joshua’s experience is far from unique. Too many learners find themselves left in the dust by assessments that test the wrong things, at the wrong time, using the wrong measures.

And the cost of getting assessment wrong can be very high indeed, as Joshua points out:

“So often the pressures of the school system can break a student easily and quickly. And it becomes really difficult to come out the other side and still be a strong candidate when the only important thing is what grade you got.”

So what is so wrong with assessment? And why are these failings especially problematic and potentially harmful for neurodiverse learners?

Five Things Wrong with Assessment in Schools

1. Schools assess all learners at the same time

Partly because of the way the school year is constructed and partly driven by the drop-deadlines of national standardised testing at 16 and 18, assessments in schools follow a rhythm that is largely dictated by how much of the curriculum it is possible to cram into any given period. Learners study skills and knowledge through the curriculum and then teachers (or exam boards) use assessments, usually tests, to measure how skilled or knowledgeable learners have become after an allotted time has expired.

This model is so familiar that it feels like the only sensible way to approach the timing of assessment. It isn’t. In most other aspects of their lives where learning features, learners choose, with the help of their teacher or mentor, when is the right moment to complete an assessment. From gymnastics badges to music grades; the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award to driving tests, learners and teachers work together to agree the best moment to assess progress. By assessing all learners at the same time, schools ignore everything we know about how learning happens, specifically that different learners learn different things at a different pace and that the right moment for assessment – the moment that is optimal for learning – will therefore be different too.

What if… individual learners and their teachers could decide together when to begin a formal assessment, at a time when each learner feels ready and confident to “take the test”?

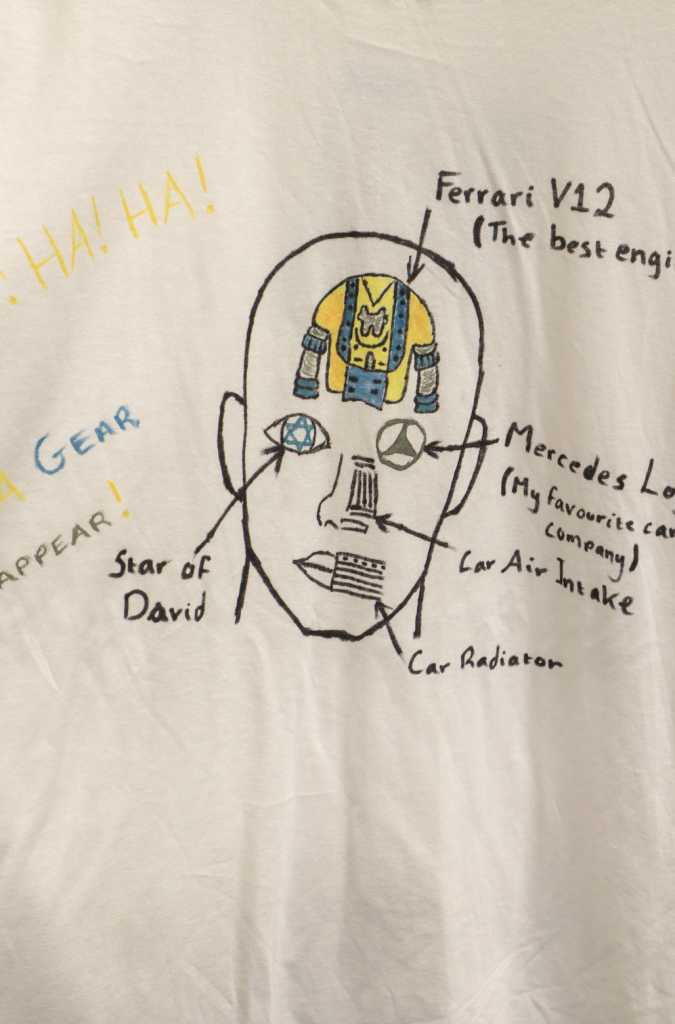

2. Schools only assess what’s taught in school and/or by teachers

“I can make a video game using languages that the curriculum doesn’t even know exist, but none of them get recognition. I can do all this stuff and it doesn’t matter because it wasn’t what I was told I had to do. I didn’t fit that specific guideline and therefore it’s not good enough.” Joshua

Curriculum so dominates in schools that not only does it dictate the pace of learning, it can also constrain the scope of learning too. This may be an unintended (but not unnoticed) consequence, amplified by assessment, which concentrates on learning that is delivered in school and by teachers and ignores learning that happens at home, in sports clubs, dance or music schools, or anywhere where it is unseen by teachers.

What if… schools could recognise learning that takes place in these other settings and celebrate the full range of knowledge and skills that learners have acquired?

3. Schools assess everything that is taught in schools and/or by teachers

In the interests of leaving as many doors open as possible for learners’ futures, schools crowd their timetables with curriculum and assessments, some of which are, for the vast majority, irrelevant to where learners want to go next. This squeezes out other learning opportunities that might actually engage and inspire learners to choose and follow a path they can feel passionate about. Schools waste so much time deciding what learners should care about and what help they might need to get there when, with a little more trust, curiosity and empathy, they could simply ask them. And many learners are exhausted by cramming for tests across a much wider range of subjects than they could ever possibly need.

What if… individual learners could choose to be assessed in specific areas of their learning only where a standardised recognition or qualification is helpful?

4. Schools (mostly) assess learning when learning is ‘finished’

There is no question that many teachers skillfully incorporate formative assessment into their practice, for example, in how they ask questions in class and the assignments that they set. However, it is also the case that most formal assessment of the kind that makes it onto report cards and transcripts happens at the end of modules or units of learning when they are summative and final, often pass or fail, and always too late to act upon.

What if… learners could practise assessments numerous times and get the feedback they need to achieve mastery, before deciding to “take the test”?

5. School prioritises assessments that schools and teachers are judged on, not assessments of most value for learners

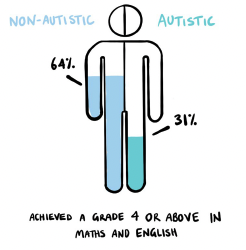

In our highly regulated education system, it is unsurprising that the people who lead schools are anxious to demonstrate that their school and their staff can deliver the results that the system demands. Reputations and livelihoods depend on it. Unfortunately, the system, comprising around 24,000 schools serving just under nine million learners in England, also requires those results to be demonstrated with a high degree of standardisation to facilitate judgments about quality, consistency, value for public money and so on. Standardisation also helps keep costs down and makes moderation possible (although not inevitable, as is demonstrated by the removal of several education ministers shortly after results day).

This is all very understandable and has really very little to do with learners and their individual or personal needs, now and for their futures. Worse, it produces assessments and a related culture which, as we have seen, are arguably not in any learner’s best interests and, for some learners, can be horribly damaging.

“Assessments led me into a very unhealthy revision cycle. Assessment as it is now is not actually really a test of knowledge, but more a test of memory, so you end up sitting in a Costa drinking more coffee in one hour than I would in a week normally, just to stay awake, then sleeping three hours a night, cramming knowledge just to end up being tired on the day and messing up the exam.” Joshua

What if… schools were empowered to assess and celebrate learning that was of the highest value to the learners and communities they serve?

Professional Prompt Questions

-

Which two of these five “What if…” statements most resonate with you? What would you need to do to introduce practices that were consistent with them?

-

How might you assess and recognise young people’s achievements outside the classroom and at home?

-

How might the agency of young people feature more strongly in the assessment approaches at your school?

Some Lessons For Any School

Some Lessons For Any School