Ron Berger: An Interview

Ron Berger is internationally recognised for his educational wisdom and insight. He was a public school teacher and master carpenter in his early career and those craft values now inform his educational leadership. He is Chief Academic Officer for Expeditionary Learning, which embraces over 300 schools across the United States, and he also teaches at Harvard Graduate School of Education.

This is the second instalment of our interview with Ron. He is a wonderful storyteller as well as a wise educator — might those things just be linked? Anyway, it is so rich that we are feeding it in small servings! Towards the end, he talks about a lovely project done by ten-year-olds. In the Resources for Teachers section, we have included a teaching guide to that project.

Critique and multiple drafts

Rowan Eggar, Assistant Head: Curriculum & Assessment at Gesher

How can we best support kids to make critiquing and drafting a dynamic process, as opposed to them being basically annoyed because we are having to review again? So that’s my question: What ways are there to design drafting and critiquing so that you can get the best possible outcome for the students?

Ron Berger

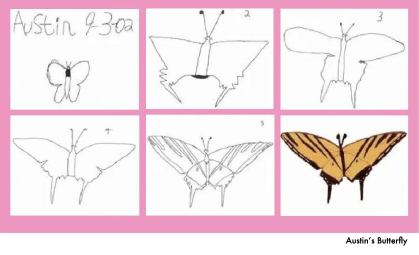

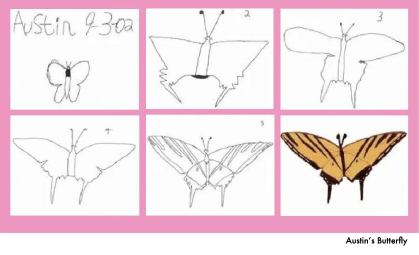

Great question. I think the way I’m most known in the world is the Austin’s Butterfly video. And so people understand I am obsessed with kids polishing their work and doing multiple drafts, but it’s not easy, as you say. So, I can give a few reflections on that.

The first, I would say, is that it’s only useful to keep doing drafts if the work keeps improving, if kids can see improvement happening. After that, there is no need to make them do six drafts. There’s not a magic thing that says Austin did six drafts, so therefore everyone should do six drafts. Austin’s work actually kept getting better, and that’s why it made sense for him to keep pursuing that drafting process in the video. One of the things that we can see in the Austin’s Butterfly video is that Austin had a reason to do six drafts, which was, importantly, that there was an audience for that work that he really cared about.

The butterfly Austin drew went on a card. It was sold across the entire state of Idaho. Wow. And all that money was used for butterfly habitats. And so his drawing was supposed to be so good that people would be able to use it to identify the actual butterfly, which is a reason why his first draft wasn’t that useful because you couldn’t actually identify the butterfly from that draft. Some art teachers have critiqued me for making him do something that’s very mechanical but that’s because this isn’t an expressive art project. It’s a scientific illustration. And so there was a reason for him to care about getting it right. And the kids in the video also had that photograph that they were looking at. So they knew what it should look like and felt empowered to say, ‘I can see what’s different about your drawing from that photograph.’

There’s a couple of things to take away from that. One is just the motivational thing. When kids have a purpose for their work that’s beyond their classroom, a real social purpose, a purpose they care about, then they’re way more motivated to do more drafts. Is there a way that what they’re creating can be used for something that matters a lot to them and where they really want it to be good?

For example, I went into a first-grade classroom where kids were working on letters, writing letters, and they were Y2, second years in the US. And they were still working on some of the basics of capitalisation and punctuation and ending sentences and writing legibly. They were young kids, they were six and seven years old, but they had visited the local fire station where they had met firefighters. And so instead of doing practice, they were actually writing a personal letter of appreciation to each firefighter and each student was assigned a firefighter.

A second thing is, do they have a model of what good looks like? If they have, then they can give critique.

So, if I were assigned Loni to write to, I would think, oh my goodness, I’d better get this letter to be perfect because I’m writing to this woman, who’s a firefighter, who’s protecting us, and she’s going to put it up on her locker and look at it every day. I want it to be perfect. I want my lettering to be perfect. I want my punctuation to be perfect. I want my spelling to be perfect. And so there was not a lot of pressure to say to kids, ‘You have to do another draft.’ It was like, ‘I need to keep making it better.’

A second thing is, do they have a model of what good looks like? If they have, then they can give critique.

So if I’m working on my thank you letter for Loni as a firefighter, and Ali is a peer of mine and she has a model of a thank you letter that we’ve all looked at together, a really good one, she can say, ‘You know, Ron, yours doesn’t have this actually. And notice how this one has it.’ And so it’s easier for her to give critique. And it’s easier for me to think, ‘oh yeah, you’re right, I didn’t do this. I didn’t do that’. And I know that we are often, as a culture, afraid to give kids models because we think, oh, what if they copy? But I have an entirely different attitude towards that, which is that copying is how we learn. So if we, as adults, want to learn to do something new like play guitar or speak Danish or do yoga, what do we do?

We go to a class or we go online and we watch somebody do it, and we try to copy them. And then we get critiques about what we’re not doing. Right? And then we try to copy them again. And we keep trying to copy them. We don’t start by improvising, right? We start by watching how they do a yoga pose, listening to how they pronounce something, watching how they do a chord on the guitar. And then we copy it. And then we critique ourselves and we get critique from others.

Modelling is how all of us as adults learn. We should not be afraid to show kids models of what a good letter is, what a good maths solution is, what a good anything is and to agree together why it is good. And then that empowers the kids to critique each other.

So I think it makes sense that kids get frustrated because they feel like ‘I just wanna be done. And you’re just delaying.’ The dynamic is totally different when you feel that this is what we’re aiming for. It’s about giving kids more power over it, by it not being us, the ones telling them it’s not ready, but them being able to see themselves.

Rowan

Amazing. Thank you. That’s really helpful!

How do we know our children well enough to understand what is relevant or right for them?

Ron

Teaching is about relationships. If you want to draw the best out of each kid in your school, in your class, in your group, it’s really about knowing that kid. It’s knowing what they’re proud of, knowing what they’re worried about, knowing what motivates them, knowing where their heart is. And if you want to draw them out, you have to know when it’s okay to tease them and what you can tease them about as a way of showing that you love them.

It’s all about relationships, but that doesn’t mean that we have to individualise what every kid works on. I think that’s a mistake we make, thinking that knowing kids well and loving them and caring about them means that I have to have a totally different task for Rowan, for Loni, for Ali and for Charlotte because one’s interested in dogs and one’s interested in cats etc., so they can’t do the same task as it’s not their passion. I don’t believe that. I believe sometimes kids should be able to write about their passion, read about their passion, do projects about their passion. But I think there’s a side of all of us that wants to do some good for the world.

So, it’s not just a question of passion. It’s a question of if you’re a human, you also want to do something appreciative for others.

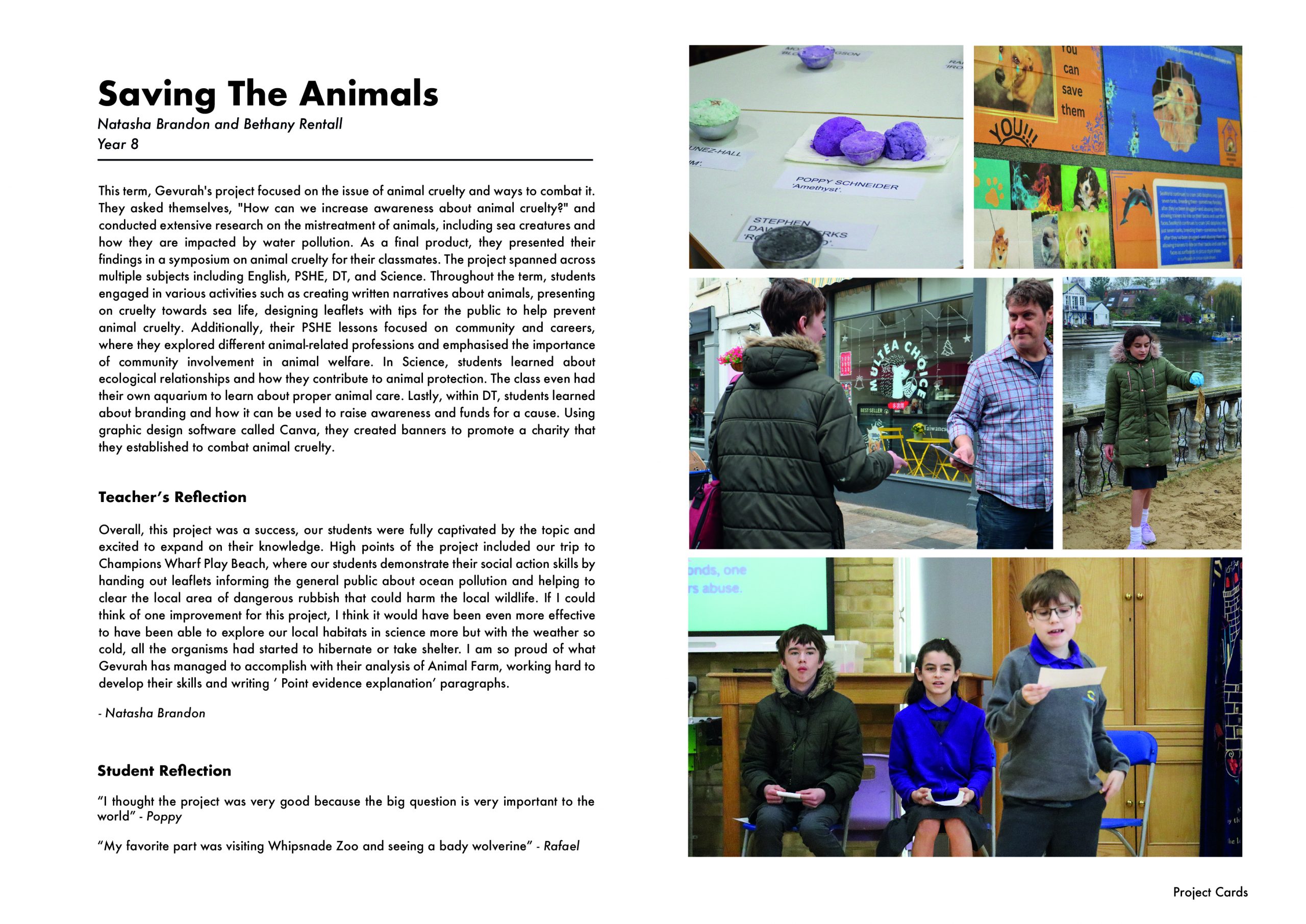

I’ll share another story, a project from year fives (10 or 11-year-olds) in Moscow, Idaho, another rural community in the United States. All the kids were brought to an animal shelter and each kid was paired with an animal. Now, this is not an animal that they’re going to be allowed to take home. Their parents are not going to say: ‘You can take this stray dog home or this stray cat. But the kids learned the story behind each animal. What do we know about this dog? What do we know about this cat, her past, what she likes, what she’s afraid of — what do you know?

So they learned the story of their animal. They took a picture of their animal and then they went back and they did a portrait, an artistic portrait of their animal based on the photograph they had. And they did many drafts because there was a real purpose for this. The purpose was that they wanted their animal to be adopted. Oh, wow. Then they wrote a poem about the story of that animal, what they had learned about that animal’s past. Then they took the artistic portrait they had drawn and they took the poem that they had written about the animal, both of which had gone through drafts and they made a poster of it and they laminated those posters and they put them up all over town.

Now, if you’re in the laundromat, and if you are in the motor vehicle registry where you get a driver’s licence, or you’re in the doctor’s waiting room, there are posters of all these animals with poems and portraits. And once those went up all over town, guess what, people started adopting those animals. Because how much can you look at these beautiful animals on these posters without thinking’ I’ve got to adopt that one right there’.

So there was a tremendous reason for kids to care about multiple drafts of their poems and multiple drafts of their drawings and to get critique from each other and from the teacher and from experts. But we didn’t have to think, oh, that’s not a kid who likes dogs, or that’s not a kid who likes cats, therefore we won’t bring her on this trip. We just assumed, correctly, that every kid would understand the human quality of ‘we can save these animals’ lives — if we’re really good at this.’

… my students would be so motivated by that project.

Rowan

Yes. Purpose and agency. I’m just thinking already, my students would be so motivated by that project. That sounds like a dream project. Absolutely amazing. Love it.

Ali Durban, Gesher Co-Founder

It also emphasises the connectedness to the real world which, especially for our students, makes learning much more tangible — rather than knowledge that floats around that doesn’t actually mean anything.

Editor’s Note

A Project Card to support this project has been included here in the Resources for Schools section.